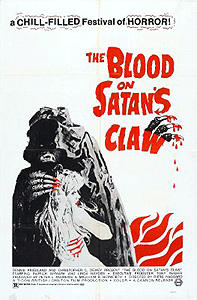

The Blood on Satan’s Claw/Blood on Satan’s Claw/Satan’s Skin (1971) ***½

The Blood on Satan’s Claw/Blood on Satan’s Claw/Satan’s Skin (1971) ***½

I’m a sucker for a good intro. Whether it’s a movie or a song or a book or a TV show, a strong first impression will get me to forgive a lot more screwing around than usual while a work of art gropes its way along to the point. The Blood on Satan’s Claw has a great intro. Ralph Gower (Barry Andrews, of Terror Under the House and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave), a plowman working for Isobel Banham (Avice Ladone), is tilling his landlady’s fields when he notices that a certain spot in the furrows behind him has attracted a great swarm of scavenging birds. When Ralph goes to investigate, he finds a disturbingly human-looking tailbone, a mass of black and gray fur, and the decayed remains of a face, neither human nor animal, staring up at him from the freshly turned earth with a single glassy and unaccountably preserved eye. I had never, ever heard of this movie when it played on “Joe Bob Briggs Drive-In Theater” many years ago, and I hadn’t really been in the mood for a period piece at the time. After seeing that opening, though, there was simply no way I could resist. A good thing I couldn’t, too, because The Blood on Satan’s Claw turned out to be among the very best of the highly idiosyncratic horror films released by London’s short-lived Tigon studio during the late 60’s and early 70’s, and I’d have been very irritated with myself later on for not giving it a chance that night.

Anyway, Ralph immediately does what any right-thinking 17th-century English peasant would do under the circumstances— he runs off at once to report what he found to the circuit court judge (Patrick Wymark, from Children of the Damned and The Skull) who is currently tarrying in the village to visit Mistress Banham (who, incidentally, turns out to be an old girlfriend of the judge’s). His Lordship is not impressed with the plowman’s tale of fiendish carcasses buried in the local farmland. Far from the sort of Satan-fixated magistrate that one expects to encounter in horror films with this setting, this particular judge sees himself as an agent of enlightenment, using the power of his office to battle the forces of ignorance and superstition. Nevertheless, he eventually permits himself to be led out to the field to see the half-buried thing for himself, but there’s no longer any sign of it anywhere, and the movement in the underbrush yonder turns out to be nothing but the Reverend Fallowfield (Anthony Ainley, of Exorcism at Midnight and The Land that Time Forgot) chasing after a small snake.

That evening, the judge finds himself in the middle of a different sort of hubbub, for Mistress Bahnam’s nephew, Peter Edmonton (Simon Williams, from The Touchables and The Uncanny), has brought his new fiancee, Rosalind Barton (Tamara Unstinov, of Blood from the Mummy’s Tomb and The Last Horror Movie), over to have dinner and spend the night, and the old lady does not approve of Peter’s taste in women one little bit. Peter personally believes that his aunt suspects him of having gotten the girl knocked up, but close attention to Isobel’s carping suggests that she considers the Barton family to be her clan’s social inferiors. In any case, poor Rosalind finds herself banished to the attic when bedtime rolls around, the judge having already claimed the guest bedroom and Isobel having refused to consider letting Peter relinquish his own room. This is a bad thing for Rosalind not just because the attic is musty, cluttered, and generally not fit for human habitation, but more importantly because there’s something alive beneath the floorboards up there— something like that fiend from under the field, perhaps? Whatever it is, Rosalind wakes up the whole house with her inarticulate screaming, and nothing the family, the household servants, or the visiting judge can do is enough to quiet her hysterics. Indeed, Isobel gets some nasty scratches across her face when she intervenes. When the village doctor (Howard Goorney, from Berserk and Crucible of Horror) comes to examine her in the morning, Rosalind has withdrawn into a calm far more unsettling than her earlier mania, and the verdict is that there’s nothing for it but a trip to the madhouse. If you’re asking me, though, everyone’s attention should be focused less on Rosalind’s mind than on her right hand, which has somehow transformed over the course of the night into a black-furred talon.

We may presume that it was the transfigured hand that injured Mistress Banham, for she immediately comes down with a severe, delirium-producing fever, and eventually wanders off into the countryside in the midst of a thunderstorm. Justice Middleton (James Hayter, from The Horror of Frankenstein and The Four-Sided Triangle) raises a posse to search for her, but no one finds a single trace of the old woman. And as if the past 24 hours haven’t already sucked more than enough for Peter, he too runs afoul of the thing under the floor when he goes to mope himself to sleep in the bed that was prepared for Rosalind in the attic. This time we get to see a bit of it for ourselves— a taloned arm exactly like the one Rosalind was sporting, which lunges up from beneath a loose board, wrestles Peter down to the bed, and nearly strangles him before he seizes a knife from among the attic’s clutter and hacks it from its unseen body. But when the judge and the servants rush upstairs to see what all the commotion was about, we see that the hand Peter severed was really his own!

Life in the village does not get any less weird after the judge rides off to meet his next round of legal obligations in London, taking with him for further study an occult book lent him by the doctor, which contains an account of events suspiciously similar to what transpired in the village over the past two days. Reverend Fallowfield sees the continuing abnormality first in his capacity as schoolteacher, for a veritable plague of unruliness breaks out among his pupils, seeming to center upon an adolescent girl named Angel Blake (Linda Hayden, of Taste the Blood of Dracula and The Boys from Brazil). What Fallowfield doesn’t recognize is that the mysterious object with which Angel has been so successfully outcompeting him for the attention of her classmates is the last joint of a wickedly clawed finger— another fragment of the unnatural carcass Ralph dug up with his plow. Contact with the claw seems to produce two different sets of effects, perhaps depending upon the natural temperament of the person who handles it. Some, like Angel herself, become rebellious and wicked, blowing off their responsibilities to gather under the girl’s leadership in the ruins of a church deep in the woods, where they fall in with a pair of elderly hermits who fit very well the stereotypical conception of witches. Others, like Mark (Robin Davies) and Cathy (Wendy Padbury) Vespers, the children of Isobel Banham’s maid (Charlotte Mitchell, from The Man in the White Suit and Village of the Damned), come down with inexplicable body aches and eventually sprout patches of matted, black fur from the skin over the affected area. The former group then begin preying on the latter, ritually murdering them to extract whatever flesh has grown over with that unholy hair. This they offer up to a horrid— and horridly incomplete-looking— creature which we may take for Ralph Gower’s fiend, back from the dead and gaining more strength with each organ, limb, and slab of tissue that Angel and her juvenile cultists harvest for it. Meanwhile, Angel takes steps to neutralize the one person in the village who might pose a credible threat to her and her followers, first attempting to seduce the Reverend Fallowfield, then accusing him of raping her and murdering Mark Vespers when that fails. In the end, matters spiral so far out of control that Peter Edmonton mounts his horse and sets out on the road to London, in the hope of persuading the judge that supernatural evil truly is afoot in the village. As it happens, the judge is already way ahead of him, won over by the contents of the doctor’s old book and more than ready to return to the village and get his Matthew Hopkins on.

The Blood on Satan’s Claw strikes me as a movie that is unusually vulnerable to over-praising. It’s good— I mean, it’s extremely good— but its creators made some strange and indeed outright foolish decisions along the way that have left their unsightly marks upon it. The plot, to begin with, is perhaps just a bit too busy, with a few too many parallel threads, and keeping track of the overly numerous characters and their insufficiently established relationships to each other can get confusing. Presumably this is a side-effect of the movie’s origin as an anthology of thematically linked stories; the producers decided sometime during preproduction that they’d rather have a regular feature-length film, and what were designed as three self-contained scenarios— the thing in Peter Edmonton’s attic, the activities of Angel and her coven, the battle between the judge and the reconstituted fiend— were braided together into a single tale. The characterization of the judge is less coherent than it ought to be, and too much of his conversion from oracle of enlightenment to hands-on devil-slayer happens out of our sight. An important line of his dialogue is seriously misplaced, too, and The Blood on Satan’s Claw would have been significantly improved simply by moving it to a later scene. Linda Hayden’s stellar performance as Angel is hampered by a pair of “diabolical” eyebrows that the young demoniac grows for no very good reason after running away from home to pursue her devil-abetting activities full time. Seriously, it’s a shame that acting of this caliber should have to compete with such a distractingly bad makeup job, especially since Hayden needed absolutely no artificial assistance to change her affect from vibrantly mischievous to thoroughly depraved. Finally, the climax is just a little bit of a letdown. It feels like part of the exposition leading up to it went missing, for one thing. Going by the reverence with which the judge and his impromptu army handle the claymore he uses to dispatch the fiend, I gather that we’re meant to interpret it as something more than just a really impressive antique sword, but what if any special significance the weapon has is never revealed. I know that certain medieval traditions credited iron (or sometimes iron forged according to some specific technique) with an efficacy against devils similar to that which silver supposedly holds against werewolves, but I wouldn’t go presuming my audience to know that if I were making a movie. Also, the fiend itself is ill-served by the final showdown, simply because we get entirely too good a look at it. With its indecipherable features, piecemeal figure, and metallic buzz of a voice, the creature is effectively creepy for most of the film, but it’s far too cheaply made to stand the scrutiny it gets during the concluding scene.

All those caveats aside, though, The Blood on Satan’s Claw is well worth investigating for fans of both latter-day Brit-horror and turn-of-the-70’s diabolism. The period setting is perfectly convincing, from the costumes to the settings to the attitudes on display among the characters, and if you ever want to hear 17th-century English grammar done right in a movie, look no further than this one. Linda Hayden’s is not the only powerful performance, and it is much to the film’s credit that that’s true even among the other village kids. Patrick Wymark is good enough that the defects in the writing for his character barely matter most of the time, and the conviction with which he vows to use “undreamed-of methods” to combat Angel and the monster whose bidding she does is such that you probably won’t notice until afterwards that his “methods” amount to no more than a couple of dogs and a birch rod. The pace is deliberate but well-chosen, with nicely executed scare set-pieces at regular intervals. And of course I’ve already mentioned both the kick-ass opening scene and the eeriness of the monster so long we’re shown it only in glimpses and snatches. The highest commendation I can think of to give The Blood on Satan’s Claw, though, is that it does not meaningfully resemble any other movie I’ve seen. Although nominally gothic horror, it eschews the usual settings for such things, trading the baronial castles and towns of a generically Germanic 19th-century Europe for an English peasant village during the aftermath of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and it injects into this atypically specific and markedly premodern venue an obvious parable for the youth unrest of the early 1970’s. Its hero is a man whom we would naturally expect to be the villain on the basis of contemporary movies like The Conqueror Worm and The Bloody Judge. And although it concerns itself with the then increasingly popular subject of diabolists conspiring to bring the object of their worship into the physical world, it does so via a far more imaginative means than the Satanic impregnations of Rosemary’s Baby and To the Devil… a Daughter. It might be the weirdest outlier of the whole 1970’s occult horror vogue, and weird outliers are always worthy of some celebration, so far as I’m concerned.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact