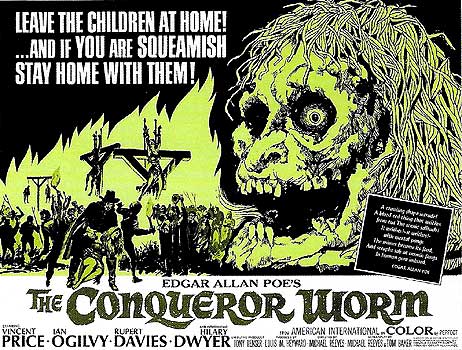

The Conqueror Worm / Witchfinder General / Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General (1968) ***½

The Conqueror Worm / Witchfinder General / Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General (1968) ***½

Throughout the early-to-mid-1960’s, Roger Corman’s Poe movies were among the biggest money-makers in the American International Pictures catalog. Not only were they huge draws at the box office, they didn’t cost that much to make, and so AIP’s profits from them were truly extraordinary. So when Corman decided he’d had enough after 1965’s The Tomb of Ligeia, there was little question but that the studio would find other directors willing to keep cranking the things out. There’s one big difference, though, between the two sub-sets of Poe flicks. Corman’s, though they generally diverge noticeably from the plots of the original stories, at least appear to have been made by someone who’s read them. The later, non-Corman films often bear no resemblance to their supposed sources at all. Compare the movie The Oblong Box to the story from which it takes its title. Not even close, is it? Then have a look at something like War-Gods of the Deep, which claims to be derived from the poem “City in the Sea.” Beyond the fact that both poem and movie feature an underwater city, there’s no visible connection whatsoever. The Conqueror Worm (made in partnership with Britain’s Tigon studio) takes the phenomenon one step further still— look for anything in the movie that remotely suggests the poem of the same title, and you will do so in vain. If anything, it would seem that AIP had adopted a deliberate policy of slapping a Poe title on any movie they made that echoed the style of Corman’s older films. Small wonder, then, that the rest of the world knows this movie by the altogether more sensible titles Witchfinder General and Matthew Hopkins, Witchfinder General.

What we have here is one of the first of the late 60’s/early 70’s witch-burning movies, and a strong contender for the arguably dubious honor of being the best of the bunch. It is set in England in 1645, during the civil war between King Charles’s royalist party and Lord Oliver Cromwell’s parliamentarians. As the film opens, one of Cromwell’s soldiers, a man named Richard Marshall (Ian Ogilvy, from And Now the Screaming Starts and The She-Beast), is on his way home from the front lines for a short rest between tours of duty. His first stop when he reaches his old village is the home of the neighborhood priest, John Lowes (Rupert Davies of The Crimson Cult and Dracula Has Risen from the Grave). The reason for Marshall’s visit has less to do with Lowes than it does with his niece Sara (Hilary Dwyer, from The Oblong Box and Thin Air), whom Marshall has loved since he was a boy, and whom he hopes someday to marry. To the cavalryman’s surprise, old John not only gives his blessing to the marriage completely unbidden, but insists that it be carried out posthaste, and that Richard and Sara go as far away from the village as can be arranged immediately thereafter. Lowes, you see, has begun to fear his neighbors, who for unexplained reasons have been spreading slanderous gossip about him, to the effect that he is at best a secret Catholic, and at worst a practicing Satanist. This would have been cause for concern at the best of times, but with the mechanisms of civil authority strained to the breaking point by the civil war, it would be easy for whatever resentments underlie those rumors to erupt into lethal mob violence. And if that happens, Lowes wants his niece far from ground-zero when it does. Unfortunately for all concerned, Marshall’s military duties prevent him from taking Sara away at just that moment, but Richard gives his word that he and Sara will be married the moment he is free of his obligations.

As fate would have it, that just isn’t good enough. When Richard rides off the next day to rejoin his regiment, he passes a group of villagers who say they await the arrival of a lawyer from out of town. Later on, he encounters two horsemen— a tall, thin man of perhaps sixty years and a much younger one who gives the instant impression of being something of a thug. The older man is Matthew Hopkins (Vincent Price), the lawyer of whom the villagers spoke. The thug is his assistant, John Stearne (Hell Mountain’s Robert Russell). As you might have guessed on the basis of Price’s casting, these men are the bad guys— amateur, freelance inquisitors, roaming the English countryside on the hunt for witches. And as you might also have guessed, the townspeople have summoned them forth to prosecute (or would “persecute” be the better term?) John Lowes.

Hopkins gets to work immediately, having Lowes arrested and locked in the town dungeon, to which the local magistrate has helpfully given the witch-hunter free access. There, the priest is tortured by Stearne until Hopkins notices something that makes him change his tactics— Sara. Hopkins enlists Sara’s cooperation in “proving Lowes’s innocence,” an arrangement which, in practice, is indistinguishable from a simple quid pro quo. Sara allows Hopkins full use of her exquisite body, in exchange for which Hopkins restrains Stearne from brutalizing her uncle. But Stearne is not as dumb as he looks, and he catches on to the situation quite swiftly. And once he figures out what’s going on, he becomes most resentful of his partner’s efforts to keep the best-looking girl in the village all to himself. When Hopkins takes a day off to go visit a neighboring town, Stearne takes advantage of his boss’s absence to force himself on Sara. One of the townspeople spies him raping the girl in a field, and tells Hopkins about it upon his return. In the villager’s version, however, Sara gave herself to Stearne willingly— in effect breaking her end of the unspoken bargain for Lowes’s life. The priest is executed just days later, along with a couple of other “witches,” and then Hopkins and Stearne collect their fee from the magistrate and move on.

Shortly thereafter, Marshall gets another opportunity to visit Sara, and when he does, he learns all about Hopkins and his deviltry— the rape, the murders, the sexual extortion. He holds a sort of DIY marriage ceremony for himself and Sara in the vandalized ruins of Lowes’s chapel, and then packs her off to what he thinks is a safe place, swearing at the same time an oath of revenge against Hopkins and Stearne. The rest of the film concerns Marshall’s hunt for the evildoers, a quest which will nearly cost him his career, and which leads him ultimately to the very town to which he sent Sara, where both he and his new bride will face the full fury of Hopkins’s semi-legal terrorism. The Conqueror Worm’s conclusion may just be the grisliest thing ever to have happened in an AIP film up to then— it’s certainly a far cry from the bloodless ending of I Was a Teenage Werewolf!

The thing that really struck me while I watched The Conqueror Worm was the contrast between it and Mark of the Devil, a film on the same theme made only two years later. It’s amazing to me what a difference those two years made. The Conqueror Worm, though often quite gruesome by the mainstream standards of its time (and remember that AIP was very much a mainstream studio in those days), never comes close to matching the sliminess of the later film. Stearne’s idea of torture is mainly to slap his victims in the face repeatedly, occasionally switching to the church-sanctioned stiletto-in-the-back technique for added effect. There are a few scenes which hint obliquely that he occasionally goes all-out when the camera isn’t around, but mostly what we see is a whole lot of face-slapping. The stomach-churning sadism for which the inquisition movies are, for the most part, justly famous simply isn’t on display here. On the other hand, a clearly thought-out, complex, involving story, making good but sparing use of convincing historical background, is. While there are a couple of jarring anachronisms (for example, I find it hard to swallow the idea that country people would have taken such a blasé attitude toward pre-marital sex— in a priest’s house, no less— in 1645), the period setting is mostly believable, and lends a surprising amount of authority to the film’s main action. The characters are, for the most part, convincingly drawn and skillfully realized by the actors portraying them. Price is especially good, putting in an expansive, robust performance without straying into the territory of self-parody that he so often trod in his long career. Ian Ogilvy does an admirable job, too, for most of the movie, although he allows Marshall’s final descent into feral, kill-or-be-killed viciousness to come completely without warning, robbing the scene in which it happens of much of its potential effect. On the whole, The Conqueror Worm makes for both a fascinating case study of the horror genre at a time of momentous stylistic transformation— a sort of missing link between the neo-gothics of the early 60’s and the gore-core flicks of the 70’s— and for a superior evening’s entertainment in its own right. Not a lot of movies can honestly make such a claim as that.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact