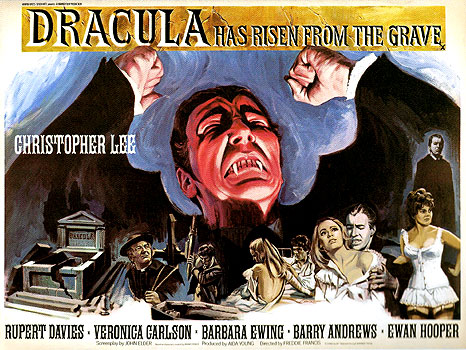

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968/1969) **˝

Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968/1969) **˝

It’s funny. The Dracula franchise is probably what Hammer Film Productions is best remembered for today, but those movies are consistently among the studio’s weakest products. The worst of the bunch are among the few truly terrible Hammer films I’ve seen, and even the best of them wouldn’t make it into my personal top ten. For the most part, they’re just sort of okay, competent in an undistinguished manner, but representing ever more plainly as the years wore on all the ways that Hammer wasn’t adapting to changing times. Dracula Has Risen from the Grave may be the okayest of them all. In what would turn out to be the most transformative year in horror movie history since probably 1931, it stands fast in the center of the genre’s comfort zone, offering a perfectly acceptable rendition of little you haven’t seen before.

We begin with events that must be concurrent with Dracula, Prince of Darkness. An altar boy (Fiona’s Norman Bacon) notices a trail of blood dripping from the bell of the church he serves. When the boy alerts the parish priest (Ewan Hooper), the latter discovers a dead girl stuffed inside, her neck disfigured by a fresh vampire bite. It’s the kind of thing the villagers thought they had put behind them after that Van Helsing guy came though, but you know how it is with the undead. As we know from the last movie, it happens that Dracula’s resurrection lasts only a few days before the vampire is drowned in his own moat— which being fed by the mountain streams is sufficiently fresh, pure, and flowing to incapacitate him. Still, even after a whole year without a vampire sighting, the villagers remain in constant terror that the evil count will rise yet again.

That persistent dread explains the scene which confronts Monsignor Ernst Mueller (Rupert Davies, from The Conqueror Worm and King Arthur, the Young Warlord) when he leaves his post in Kleinenberg to visit the hinterland village where the aforementioned attack took place. Sunday afternoon though it is, the village church is empty except for the altar boy we met before (who has been rendered mute by the trauma of his experience the preceding year), and there’s nothing to suggest that services have been conducted there anytime recently. Mueller is doubly scandalized when he finds the priest in the local tavern, getting drunk right alongside his parishioners. The priest lacks the courage to defend himself, but the publican (George A. Cooper, of Nightmare and The Brain) doesn’t mind telling Mueller that no one around here will set foot in that church at any hour when the shadow of Castle Dracula is likely to fall on it. Sure, they’ve all heard the official line about consecration driving out evil, but every man, woman, and child in this hamlet knows firsthand that Dracula’s evil is plenty strong enough to drive out good. I mean, during his last reign of terror, he stuffed that poor girl’s corpse into a church bell, for crying out loud!

Mueller quickly recognizes that something has to be done about the castle, untenanted though it may be. With that in mind, he bullies the parish priest into accompanying him up the mountain to perform a rite of exorcism on it. As it happens, Father Chickendick never actually sets foot on the grounds of Castle Dracula. Overcome by terror and exertion as darkness falls, he hangs back a bit and gets drunk again fretting over the confrontation between Mueller and whatever sinister forces still haunt the old keep. Consequently, he has a rather more eventful evening than his superior. While Mueller’s exorcism goes off without a hitch, the priest dumps himself down a ravine in his stupor, cracking his head on the iced-over surface of the stream at its bottom. The ice cracks, too— which is unfortunate, because just below it is the inert body of Count Dracula (Christopher Lee), evidently washed downstream from the moat by the current. The injured priest’s blood revives the vampire, who claims his unwitting rescuer as his latest Renfield. Monsignor Mueller misses out on all of that, returning to the village in what he assumes to be triumph when he finds no trace of Father Chickendick at their arranged rendezvous point. Mueller also misses out on the instant retribution that would surely have befallen him had he been around when Dracula found his castle exorcised and its main gate barred with the gold-plated cross from Father Chickendick’s altar, but since the priest has nowhere near the strength of character necessary to deny the vampire’s demand to know who was responsible, the smart money is on Ernst receiving only a temporary reprieve.

In the meantime, Mueller returns to Kleinenberg, going to stay with his widowed sister-in-law, Anna (Marion Mathie). He arrives just in time to take part in a birthday dinner at which Anna’s daughter, Maria (Veronica Carlson, from The Ghoul and The Horror of Frankenstein), planned to introduce her boyfriend, Paul (Barry Andrews, of I’m Not Feeling Myself Tonight and The Blood on Satan’s Claw). It looks at first glance like that should be no trouble, or at least no trouble that would sustain more than a single half-hour sitcom episode. Paul may work for Max the innkeeper (Michael Ripper, from Night Creatures and The Creeping Flesh), but he does so mainly as a journeyman baker, and he makes a point of drinking nothing stronger than beer. Furthermore, the boy has ambitions of bettering himself, and the baking gig serves only to finance his tuition at Kleinenberg’s university. What’s not to like, right? Well, there is the trifling little matter of Paul’s atheism— and also the slightly less trifling matter of his inability to keep his big fucking mouth shut. By the end of the night, Maria is in tears, Ernst is red-faced with indignation, and Paul is back at the inn, drinking himself stupid after hours with Zena the barmaid (Barbara Ewing, of Torture Garden and Haunters of the Deep). So much for abstaining from schnapps…

The Great Birthday Scandal of 1905 is the least of the Mueller family’s worries, though, because Dracula has indeed followed Ernst to Kleinenberg— and he’s the kind of guy who won’t scruple for a second to attack his enemies via their loved ones. On his first night in town, the count enslaves Zena with a sub-lethal blood-drain, then uses her to install Father Chickendick in the garret of the inn and himself in a little-used corner of its basement. The priest’s job is to keep his ears open for information that might be useful in prosecuting his master’s vendetta, especially the location of Monsignor Mueller’s house. He quickly learns not only where Ernst lives, but also that the monsignor has a niece whom he dotes on as if she were his own child. Maria thus becomes the immediate focus of Dracula’s energies— I mean, why just kill a guy when you can deprive him first of the thing he loves most, right? Of course, any attempt to harm Maria will be tantamount to opening a second front in Dracula’s private war, because Paul is sure to make it his business to defend her, whatever her mom and uncle think of him. Maybe an atheist can prevail where the religious have thus far failed.

Big surprise: no he can’t— or at least not without first accepting Jesus. Surely you weren’t really expecting such overt radicalism from a Hammer film of the 60’s? That’s actually what annoys me most about Dracula Has Risen from the Grave. From its church-desecrating prologue until the first confrontation between Paul and the count, this film teases us constantly with institutional Christianity’s ineffectiveness in the face of Dracula’s evil, and sets up an atheist to be the hands-on hero. Meanwhile, it makes a big deal of Paul’s adamantine ethics, portraying him as the true moral center of the film. But then Paul drives that stake through the vampire’s heart, and it doesn’t work because he is unable to recite the necessary prayers over the temporarily crippled monster! Leaving aside the departure from accepted vampire lore (to which Hammer always took an opportunistic grab-bag approach, anyway), it doesn’t make any thematic sense. Paul is a good man, an upstanding man, and above all a principled man. Indeed, standing up for his principles when explicitly invited to do so is what gets him into trouble at Maria’s birthday dinner. Mueller, meanwhile, is a smug man in love with his own authority, and Father Chickendick is a coward both morally and physically. To imagine that God prefers their vampire-killing to Paul’s is to reduce religion from the codified righteousness of Abraham Van Helsing and the previous movie’s Father Sandor to a narrow-minded matter of parroting the right magic words. Hammer’s horror films are almost always philosophically conservative, but Dracula Has Risen from the Grave is downright reactionary.

It also presents an amusingly petty framing for a battle between Ultimate Good and Ultimate Evil. To be fair, Count Dracula has always been a flimsy twig to hang that concept on, and this franchise has usually fared best by taking a more modest view of the stakes in play. Dracula Has Risen from the Grave scales new heights of mismatch, however, between the conflict we see and what’s supposed to be riding on it. In a film that attempts nothing less than to affirm Christianity as indispensable to moral rectitude, Dracula’s master plan is to get back at the jerk who changed the locks on his house while he was out. As silly as it is, though, I kind of love the latter idea. Without apparently realizing it, Anthony Hinds (writing as John Elder) and director Freddie Francis have stumbled upon the most perfect possible premise for a spoof of mid-century gothic horror. The Fearless Vampire Killers contains nothing half as funny as the scene here where Dracula discovers that his castle has been exorcised out from under him. Looming into the frame from stage left in extreme closeup, he snarls, “Who has done this thing?! Who has done this thing?!?!” in the most operatic display of histrionics I’ve ever seen from Christopher Lee. Hell, I’m not sure I’ve ever seen anybody get that many of their facial muscles writhing in different directions at once. And the more you think about it, the funnier it gets: of course the mortgage company foreclosed on the castle and evicted the count— he missed a whole year’s worth of payments while he was lying at the bottom of his moat! From that point, Bank of America vs. Dracula (“Whoever wins, we lose!”) practically writes itself. The only trouble is, this version is asking us to take it seriously.

On the upside, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave displays all the usual Hammer polish and professionalism. Christopher Lee often seems more grumpy than diabolical (I’m tempted to say that his subsequently oft-voiced exasperation with the studio’s handling of Dracula was starting to show), but he still contributes enough memorably commanding moments to make his performance worth seeing. Rupert Davies makes the most of a layered and flavorful character, equal parts no-nonsense bravery and stodgy complacency. Veronica Carlson’s Maria gets to be just a tad more than the expected two-dimensional good girl, and her residual shortcomings are more than compensated for by Barbara Ewing’s delightful rendition of Zena. But most of all, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave benefits from Freddie Francis’s background in cinematography. Much more than the average Hammer film, this one reveals an appreciation for the pure visual potential of the production. My favorite examples are the numerous sequences in which various characters pursue each other across the rooftops of Kleinenberg. The consistently clever and appealing imagery should generate sufficient interest to get all but the most impatient viewers through the somewhat unfocused and lethargic second act, when Dracula has yet to find his enemy and Mueller does not yet know that he’s being hunted. Nevertheless, Dracula Has Risen from the Grave remains, on the balance, an underutilized opportunity. Hammer would do better the next time.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact