Night Creatures / Captain Clegg (1962) ***½

Night Creatures / Captain Clegg (1962) ***½

If you read my review of The Last Man on Earth way back when, you may recall me spending a fair amount of space discussing Night Creatures, Hammer Film Productions’ late-50’s attempt to adapt Richard Mattheson’s I Am Legend to the screen. You might also remember me saying that the British Board of Film Censors threw a temper tantrum when they got wind of the project, with the result that it was abandoned before a single frame was shot. And yet here I am now with a review of a Hammer movie called Night Creatures; what the hell is up with that?

What’s up is that Hammer’s leadership had informed their counterparts at Universal (then one of the British studio’s most important overseas distributors) that they had a picture called Night Creatures in the works. Universal loved the title, and were eager to handle its American release. As the months stretched on into years with no sign of the coveted property forthcoming, representatives of the Hollywood firm began to nag Anthony Hinds and James Carreras about when Night Creatures was finally coming out. Meanwhile, Hammer had partnered with a wee little independent company called Major Pictures to remake an obscure 1937 swashbuckler called Dr. Syn as their follow-up to The Pirates of Blood River. The latter film had made a surprising bundle of money, especially considering that it had been aimed at the youth matinee market segment dominated in those days by imports from the Walt Disney studio, so making another pirate movie or two was a no-brainer for Hammer. It turned out, however, that the Dr. Syn project would entail a much more direct confrontation with Disney than mere competition for butts in the theater seats. Disney, bizarrely enough, were working on a Dr. Syn of their own, for broadcast as part of their “Walt Disney’s Wonderful World of Color” television anthology— and it was the studio’s usual practice to release feature-length cut-downs of “Wonderful World” serials in theaters overseas. Furthermore, while Hammer had merely purchased the remake rights from whomever owned the Gaumont British back-catalog by 1961, the Americans had cut their deal with Russell Thorndike, whose novel, Dr. Syn: A Tale of the Romney Marsh, had served as the basis for the earlier film. All the signs pointed to an intellectual property dick-fight, which Hammer was sure to lose. Remarkably, though, Disney’s lawyers were more than reasonable, and the terms of the final settlement essentially boiled down to, “No biggie. Just change the title, change the main character’s name, and make sure your version is different enough from ours that nobody gets confused as to which is which.” And when all was said and done, it would indeed have been unlikely for anyone to mistake Hammer’s Captain Clegg for Disney’s Dr. Syn, Alias the Scarecrow.

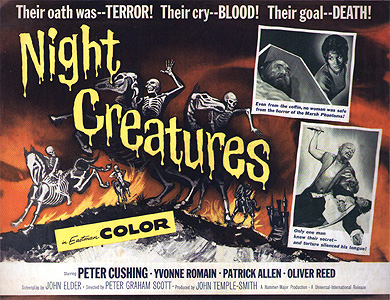

Disney’s blessing was a challenge in disguise, though, because it implicitly amounted to an invitation for Hammer to seek a much wider American release for Captain Clegg than The Pirates of Blood River had enjoyed. The trouble was that Hammer was perceived a bit differently in the States than back home. In the UK, Hammer was well understood to be an ordinary movie studio, offering an ordinarily broad range of product, even if the preponderance of their efforts went into horror films. But in America, Hammer was nothing but the outfit that made the garish Pathecolor spook-shows. A film called Captain Clegg would have seemed contrary to brand identity. Luckily, Captain Clegg was an extremely strange pirate movie. It placed far more than the usual emphasis on violence and sadism, and it featured a subplot about a squadron of ghost cavalry haunting the Romney Marsh. An advertising campaign emphasizing the undead creatures prowling the swamp by night could sucker in US audiences who expected only scares from Hammer— and oh, hey! It could be an excuse to give Universal that Night Creatures movie they were still whining about, too!

We begin with a scene that I can’t imaging having any analogue in Dr. Syn, Alias the Scarecrow. The notorious English pirate, Captain Clegg— whom we pointedly do not get to see at this stage of the film— has a serious discipline problem on his hands. He rather inadvisably brought his wife along on his current voyage of plunder, and one of his men (Milton Reid, from The People that Time Forgot and Panic) raped and murdered her. Clegg, not a forgiving sort in the first place, goes all-out with the retribution in response to so grave and personal an affront. The guilty sailor has his ears mutilated and his tongue cut out, after which he is stranded on a remote and uninhabited island without food or fresh water, tied to a sign reading, “Thus perish all who betray Captain Clegg.” The sailor has at least a little bit of luck with him, however. Clegg’s nemesis, Captain Collier of the Royal Navy (Patrick Allen, from When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth and The Body Stealer), is in pursuit of the buccaneers, and he stumbles upon the island in question while the stranded pirate is still alive to appreciate being found.

That was in 1776. Flashing forward to 1792, and abandoning the high seas for the Kentish coastal village of Dymchurch, Night Creatures next presents a scene that seems only a little nearer to Disney’s comfort zone. Between Dymchurch and the sea lies the Romney Marsh, said to be the domain of malevolent spirits. Sunset catches an elderly villager named Tom Ketch (Sydney Bromley, of Prehistoric Women and Dragonslayer) out in the marsh, and no sooner is it well and truly dark than a band of black-cloaked ghouls riding skeleton horses run him down and surround him. Ketch dies of sheer terror, and his body is discovered by some of his neighbors in the morning.

Ketch’s death is rather inconvenient for Captain Collier. No, it’s nothing to do with Clegg, although he did evade the other captain that time sixteen years ago. Rather, Collier is now assigned to enforce the excise taxes on the cross-channel liquor trade, and Ketch was promising to lead him to a ring of smugglers operating out of Dymchurch. It is a curious coincidence, though, that Collier’s business should bring him here, of all places. Dymchurch is where Captain Clegg was buried after he was hanged at Rye Prison. The details of that story are fuzzy, but apparently it was not Collier who brought Clegg to justice. And by a further curious coincidence, Dymchurch’s parson, the Reverend Dr. Blyss (Peter Cushing), was the man who administered Clegg’s last rites.

Anyway, nobody in Dymchurch is happy to see Collier or his men. Not Rash the innkeeper (Martin Benson, from The Omen and Cosmic Monsters), whose wainscoting they tear up looking for contraband. Not Jeremiah Mipps the undertaker (Michael Ripper, of The Mummy’s Shroud and The Reptile), whose shop they threaten to ransack after their efforts to get in touch with Tom Ketch lead them to his newly prepared coffin. Not Harry Cobtree (Oliver Reed, of Paranoiac and The Devils), the son of the local squire, whose political principles make him an enemy of nearly any authority (but who is paradoxically shielded from the potential consequences of his beliefs by his position among the landed gentry). And indeed not even Squire Cobtree himself (Derek Francis, from The Tomb of Ligeia and Jabberwocky), who finds himself under some suspicion due to the size and quality of his wine cellar. The only person in the village who is more than necessarily civil to Collier and his men is Dr. Blyss, and his welcoming attitude is a living illustration of the old adage about holding one’s enemies closer than one’s friends. Blyss, belying the genial face he puts forward toward Collier, is actually the smugglers’ ringleader. That makes him practically the secret head of the community, too, for it looks like Squire Cobtree is just about the only person in Dymchurch who isn’t involved somehow or other in the black-market booze trade. And as you might have guessed from the unlikelihood of an Anglican seminary offering instruction in smuggling, Dr. Blyss is not who he claims to be at all, and Captain Clegg isn’t nearly as dead as the inscription on his tomb in the churchyard would have it. Nor has Clegg lost one bit of his talent for conspiracy; not even his closest associates among the villagers know that their jolly, booze-running vicar is really one of the most infamous sea-dogs in recent memory.

Captain Collier’s revenue squad has come at a most inopportune time for the villagers. Dymchurch happens to be heavily laden with undeclared French wine and brandy just now, and there’s only so long Blyss and his fellows can keep up the giant shell game whereby they prevent Collier from discovering it. But at the same time, the captain’s presence in the village makes it very risky to ship that contraband out. Furthermore, although Collier doesn’t realize it yet, he’s holding two very powerful advantages. First, among his crew is one of the few people alive who can pierce Clegg’s disguise— the man he left to die on that island during the prologue. True, he can’t speak, and I’m sure he never learned to read or write, but Collier can’t fail to notice that the former pirate goes apeshit every time he encounters Dr. Blyss. Secondly, Clegg had a daughter, unbeknownst to most of the world, whom he placed in the care of Mr. Rash upon coming to Dymchurch in his new identity. Now that Imogene (Yvonne Romain, from Circus of Horrors and Devil Doll) is all grown up, Rash would like very much to revise the terms of their relationship, if you follow me, but she’s in love with Harry Cobtree instead. When Collier finds evidence linking Harry to the smugglers, and has him arrested, it creates an obvious incentive for Rash to turn on his comrades in crime. The smugglers have a hidden advantage of their own, however. Sailors, as everyone knows, are a superstitious lot, and Blyss and his people can count on the support of the Marsh Phantoms in their tax-evasion efforts.

So as you can see, this is not your typical pirate movie, for reasons well beyond repeating The Pirates of Blood River’s trick of spending virtually all of its time on land. (Do note, however, that unlike its predecessor, this movie does at least have a pirate ship in it, even if that ship is never seen again after the second scene.) Most conspicuously, there’s the business of the Marsh Phantoms. They’re not real ghosts, naturally, but that actually ties Night Creatures even more securely to the gothic tradition, in which criminals posing as specters are one of the oldest and most well-worn tropes. For that matter, it also links Night Creatures to the ignoble lineage of The Ghost Train, which is again a pretty far cry from Errol Flynn territory. The intriguing difference between those traditions and the way the phony ghost business is handled here is that in this film, it’s the good guys who are dressing up as spooks to scare people away from their illegal activities. Indeed, the only other movies I can think of to make a similar role reversal (apart, obviously, from the previous interpretation of Dr. Syn) are London After Midnight and its remake, Mark of the Vampire— and the imposter vampires in those films were tryin to expose criminals. Even odder, though, is what the specific nature of those illegalities means for Night Creatures. The people of Dymchurch aren’t just smugglers, after all. They’re booze smugglers. And Captain Collier isn’t just a law-enforcement agent, either. He’s out to enforce the laws levying excise taxes on the importation, transport, and sale of alcoholic beverages. You’ve seen that setup before somewhere, haven’t you? In other, mostly later, movies that have nothing whatsoever to do with piracy in the classical sense? That’s right— Night Creatures is the incognito British uncle of the American moonshiner movie! It’s a sedentary Smokey and the Bandit with a drier sense of humor and more tri-corner hats!

The aforementioned sense of humor might be the thing about Night Creatures that took me most aback. I had very few expectations about this movie going in, but it never once occurred to me that it might be funny. Yet anyone who enjoys seeing authority figures taken down a peg will find much to snicker at here. Jack MacGowan (whom my readers may remember from The Giant Behemoth or The Exorcist) has an entertaining cameo as a deceptively clever drunk who leads Captain Collier and his crew on a fruitless, time-wasting hunt for the Marsh Phantoms (which Collier already suspects of being connected somehow to the smugglers). Peter Cushing, meanwhile, shows off once again the impeccably polite rudeness that helped make his Victor Frankenstein such a joy to watch. But it’s actually Michael Ripper who steals the show on the humor front. Hammer had used him to very little effect as comic relief in some of their late-50’s gothic horror pictures, but this time they’ve given him something worthwhile to do. Jeremiah Mipps (unlike those one-note comic relief parts) is a character in the full sense of the word; being a droll wise-ass is but one aspect of his personality. Regardless, he gets easily half of the best lines. It won’t seem funny without the context, and the context is too complicated to be worth explaining here, but I’m confident that you’ll find yourself suppressing a giggle over Mipps’s “Varnish, captain. Did anyone tell you different?” at random moments for days after you watch this movie.

None of the foregoing should be taken to suggest that Night Creatures is anything less than compelling in its main role as a swashbuckling period action film, however. Cushing was still young enough and strong enough at this point in his career to acquit himself credibly in a sword fight, and Oliver Reed brings all of his usual scary intensity to a most unusual sympathetic— indeed, even heroic— part. The plot is nicely twisty (it’s times like this when I realize that the frantic busyness of Hammer’s early-70’s screeplays wasn’t totally without precedent), and goes in some surprisingly dark directions by the standards of contemporary adventure movies. And real or not, those Marsh Phantoms are a kick.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact