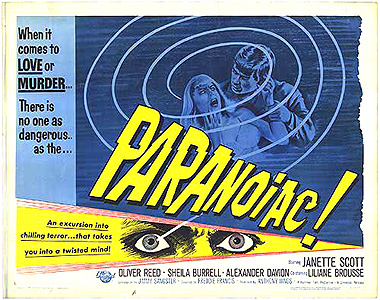

Paranoiac (1962/1963) ***½

Paranoiac (1962/1963) ***½

Eleven years ago, minor aristocrats John and Mary Ashby died in a plane crash. Three years after that, their eldest child, fifteen-year-old Anthony, threw himself from the sea cliffs forming one edge of the vast Ashby estate in despondency over their loss. John’s sister, Harriet (Afraid of the Dark’s Sheila Burrell), became legal guardian of the remaining children, and the family fortune was placed in trust with attorney John Kossett (Maurice Denham, from Curse of the Demon and The Nanny) until the kids came of age to inherit it. Simon, formerly the middle child (Oliver Reed, of Blueblood and The Shuttered Room), is now just three weeks shy of his 21st birthday, and thus on the verge of claiming his legacy. All of his relatives and their associates find this a rather frightful prospect, for Simon is a short-tempered, hard-drinking, small-hearted, arrogant, wasteful, and thoroughly vile young man. Harriet is appalled principally by his lack of concern for the family’s good name; his immoral carousing is bad enough to begin with, but he could at least have the decency to keep it out of the common villagers’ sight! Kossett objects to the profligacy with which Simon spends the money he hasn’t technically inherited yet, consistently burning through his generous weekly allowance from the trust in days and running up enormous, frivolous debts which the estate then gets sued into paying. For Williams the butler (John Stuart, from Village of the Damned and Four-Sided Triangle), the problem is Simon’s abusive attitude toward both him and Françoise (Maniac’s Liliane Brousse), the French nurse whom Harriet hired to look after Eleanor (Janette Scott, from The Day of the Triffids and The Old Dark House), Simon’s troubled teenage sister. Françoise, for her part, takes a more conflicted attitude. She hates the way Simon treats her, but she’s in love with him just the same. Furthermore, Françoise is dependent upon his goodwill, for it was he who got her the job despite her lack of qualification for it. As for Eleanor, her “trouble” is that she’s never gotten over Anthony’s death, nor indeed fully accepted that it occurred in the first place. Tony was her protector, confidant, and closest friend, and Eleanor has withdrawn alarmingly into herself in the eight years since his suicide. She’s also justly terrified of her surviving brother, who makes no secret of his desire to have her committed to a mental hospital so as to gain access to her half of the inheritance, too.

So I’m sure you’ll think you know what’s going on when Eleanor starts seeing visions of Tony— not as he was, but as the man he would be had he lived into adulthood. I mean, it’s obvious, right? Eleanor never sees Tony (Alex Davion, from The Plague of the Zombies and Whoops! Apocalypse) except in glimpses, at a distance, and no one but her ever sees him at all. Clearly “Tony” is an agent of Simon’s, and Paranoiac will hinge on a plot either to drive Eleanor undeniably insane, or to make her appear so to someone empowered to commit her involuntarily to an asylum. Not the oldest trick in the book, but still a pretty hoary one. That isn’t what’s happening at all, though. Not only does Eleanor unexpectedly make up-close and personal contact with “Tony,” but so does the rest of the family! “Tony’s” early appearances convince Eleanor that he has come down from heaven to take her into the next world with him, so she tries to hasten the process by leaping from the same cliffs as her brother, effectively reenacting his suicide. “Tony” sees her jump, however, and he dives in after her. The rescue is successful, but it throws the household into total disruption when a man who looks uncannily like a relative who’s supposed to be dead shows up at the doorstep with a waterlogged and unconscious Eleanor in his arms. The familiar stranger announces that he really is Tony, too. He faked his suicide all those years back, and his real motive for checking out was not inability to deal with his parents’ death, but inability to deal with the treatment he and his siblings received from Aunt Harriet. Williams and Eleanor instantly accept the truth of his story. After all, no one ever found Tony’s body, and were it not for the suicide note he left at the top of the cliff, his disappearance would no doubt be considered unsolved to this day. Harriet, on the other hand, just as instantly takes the newcomer for an imposter. Kossett, taking yet a third view, interviews the supposed Tony at some length, and is eventually satisfied that he’s on the level. Simon’s position, though, is hard to figure. Sardonic irony is so big a part of his personality that there’s really no way to tell what his rapid and repeated vacillation between snide acceptance and equally snide skepticism might signify. What is clear is that Simon stands to lose £600,000 from the redistribution of the Ashby estate that Tony’s return would require, and he isn’t a tiny bit happy about that. Perhaps even homicidally not happy? Could be. But again, don’t think you know what’s coming, for Paranoiac turns into yet a second completely different movie when “Tony” meets with Kossett’s son and junior partner, Keith (John Bonney, from Deathdream and The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll), to discuss the progress of a joint undertaking. The new guy is an imposter after all, but it isn’t Simon pulling his strings, nor does driving Eleanor to madness seem to be the object of Keith and “Tony’s” arrangement. It is, however, apparently a potential problem that Fake Tony (whose real name we never will learn) has taken a very real liking to Eleanor. In its third phase, Paranoiac resembles a cross between an updated, gender-flipped gothic mystery and an astonishingly prescient forebear of 1980’s slasher movies. There’s something else strange going on at Ashby Manor, you see— something that has no outwardly obvious connection to either the fate of the true Anthony or the machinations of the increasingly reluctant imposter. Somebody likes to dress up as a choirboy in a hideous rubber mask to play the somewhat dilapidated pipe organ that dominates one of the estate’s out-buildings, and to attack people with meathooks when they see things they shouldn’t have. And even that isn’t the real story…

Man… and here I thought Scream of Fear was dense and twisty! If Paranoiac is any basis for judgement, then Hammer seems to have learned a slightly different lession than most people from the success of Psycho. Among the more obvious trends that Psycho instigated was a veritable plague of twist endings, which eventually spread even to movies (The Tomb of Ligeia, for example) that otherwise bore it no resemblance whatsoever. When you really think about it, though, Psycho’s conclusion wasn’t half as shocking as its violent midstream transformation from the story of Marion Crane into that of Lila and Marion’s boyfriend. Paranoiac is most readily explicable as an effort to find the maximum number of such “all bets are off” moments that can be squeezed into a single film. Scream of Fear played a bit with that idea, too, but it never did anything as drastic as this. If you carved Paranoiac up into slivers of fifteen to twenty minutes, and showed each one to a different person, it’s a safe bet that each viewer would form a completely different impression of the total film. Incredibly, though, the story never seems to be in danger of losing coherency, even though a major plot thread is openly and explicitly dropped without ever reaching fruition. It’s one of the ballsiest things I’ve ever seen a movie do. Well into the final act, a character who has irrefutable evidence that “Tony” isn’t who he claims to be asks him directly what his game is. We’d like to hear the answer to that ourselves, for Paranoiac has reinvented itself at least twice since Keith Kossett’s scheme against the Ashby family was last seen anywhere near the focus of events. Fake Tony’s response? “It’s a long story, and it doesn’t really matter now.” That, plus the earlier scene establishing Keith as the mastermind of the scam, is all the explanation we ever get! The thing is, though, that “Tony” is absolutely right. By that point, the situation at Ashby Manor has escalated so far that whatever venal malfeasance Keith had hired him to commit is of no more importance than the concert the protagonists set out to attend in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.

Of the several faces of Paranoiac, I think the one I like best is the proto-slasher segment featuring the demonic choirboy. Those who know my tastes will not find that surprising, I expect. The masked, hook-wielding goblin is a truly horrifying creation, the incongruous elements of its appearance and demeanor coming together in a gestalt that puts all but the most unsettling of evil clowns to shame. And although the choirboy’s real identity isn’t difficult to puzzle out (there aren’t a lot of characters here, after all), the motivation for the ghastly game of dress-up rivals the psychosexual shenanigans of Psycho and Homicidal for kinky awfulness. My instinct is to say that I wish the choirboy got a bit more time at center stage, but that wouldn’t actually be true. What comes both before and afterward is too good to be foregone, even for that.

Apart from Jimmy Sangster’s nearly impossible-to-outwit screenplay and Freddie Francis’s masterfully understated direction thereof, Paranoiac’s most conspicuous selling point is yet another fine villainous turn from Oliver Reed. In 1962, Reed had just begun to be typecast in parts of this sort— unhinged, oily creeps who would be enormously attractive if they weren’t so utterly repellant. It’s a weird fate to befall an actor with Reed’s combination of talent, beauty, and screen presence, but in the final assessment, he was just so goddamned good at those roles that it’s hard to see how he could have avoided becoming defined by them. As was so often the case with Reed’s bad guys, Simon’s intellectual and emotional growth got held up somewhere in childhood, so that he now goes through life in a constant mood of aggrieved entitlement, and people have a tendency to wind up dead in the aftermath of his temper tantrums. Yet despite that, he has a clear sense of his own rational self-interest, which he pursues with a ruthlessness far beyond the years after which his personal development stalled out otherwise. In other words, he’s a lot like King in These Are the Damned, except that Paranoiac never grants Simon even the partial redemption that King enjoys in the end. He remains an intractable tangle of menace and contemptibility, with both qualities intensifying steadily all the way to the peculiarly inconclusive conclusion.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact