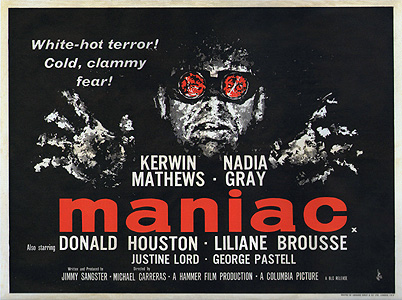

Maniac/The Maniac (1962/1963) ***

Maniac/The Maniac (1962/1963) ***

While reviewing Nightmare, I found myself wondering whether that movie or Maniac marked the moment when Jimmy Sangster really got the hang of writing post-Psycho psycho-horror. Well, now Iíve seen Maniac, and Iím still not sure. Thatís because Maniac doesnít fit at all neatly into the evolutionary pattern formed by Scream of Fear, Paranoiac, and Nightmare. Itís still recognizably psycho-horror (as any movie in which someone goes around killing people with a blowtorch would almost have to be), and itís still recognizably Hitchcockian, but Maniac owes very little apart from its title to Psycho specifically, and it doesnít rely to nearly the same extent as Sangsterís other contemporary thrillers upon repeatedly changing the terms of the story. And remarkably for a film about the unintended consequences of busting a guy out of a mental hospital, truly abnormal psychology plays only a small role here. Maniac might be better thought of as a direct descendant of The Snorkel than as part of the main lineage of Hammer mini-Hitchcocks.

In the southeast of France, between the two mouths of the river Rhone, lies a mostly swampy, sparsely populated patch of cowboy country called the Camargueó where, if we are to believe Maniacís opening text, ďviolence is never far away.Ē Itís tempting to dismiss that hyperbolic description as a manifestation of English frog-bashing, but since the French themselves seem perfectly happy to depict the non-resort parts of their Mediterranean seaboard as the domain of truculent cous rouges (see, for example, Jean-Marie Pallardyís Truck Stop), Iím inclined to suspect that thereís some truth to it. As the movie opens, the nearest bit of violence concerns fifteen-year-old Annette Beynat (Paranoiacís Liliane Brousse) and a middle-aged man called Janiello (Arnold Diamond, of Omen III: The Final Conflict and The Anniversary). Janiello is waiting in his truck near the stop when the school bus drops off Annette and a handful of boys. As soon as she separates from her fellow students to walk the rest of the way home, he pulls out into the road and offers her a ride. Annette agrees, somewhat hesitantly; she should have hesitated all the way back to her house. Luckily, one of the boys sees Annette climb into Janielloís vehicle, and this kid knows the man well enough to realize whatís coming. He races ahead on his bicycle to the Beynat homestead to alert the girlís auto-mechanic father, while Janiello detours in search of a nice spot for an afternoon rape. (It might not register in the heat of the moment that we donít get to see Georges Beynatís face, either in this scene or the one to follow, but that bit of visual reticence is going to become very important later.) Beynat speeds off at once to his daughterís rescue, but he isnít satisfied just to smack Janiello silly with an adjustable wrench. No, once the rapist is conveniently unconscious, Georges packs him up along with Annette, and brings them both home. Then Beynat ties Janiello up in his garage, and burns him to death with a blowtorch.

Four years later, American artist Jeff Farrell (Kerwin Matthews, from The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and The Boy Who Cried Werewolf) arrives in the little Camargais village of St. Jerome, ostensibly en route to Nice. Jeff, however, has grown thoroughly disenchanted with his traveling companionó a wealthy English girl named Grace (Night After Night After Nightís Justine Lord)ó and he no longer has any intention of completing the journey. Instead, he plans to hang around St. Jerome for a while, painting the Camargue. Grace can do whatever the hell she pleases, but will kindly do it far away from him. Of course, if Farrell means to paint the local scenery, heís going to need a place to stay, but thatís no problem. He and Grace have their breakup fight right out in front of a little inn with vacant rooms for rent. The owner is a sexy, 30-something woman by the name of Eve Beynat (Nadia Gray)ó which is to say that sheís Georgesís wife and Annetteís stepmother. Jeff wonít be finding this out for a while yet, but Georges was found insane by the court that tried him (the authorities, it seems, take a dim view of vigilantism even out here), and has spent the last four years in an asylum outside of Avignon. Eve is lonely, and her fortnightly visits to Georges have convinced her that his resentment of her continued freedom has finally blossomed into outright hatred. Naturally, a handsome, unattached foreigner is something she could really go for right now. So, for that matter, could Annette, and Jeff spends the whole first act being pulled this way and that, as Eve and Annette struggle over him. Itís hardly a fair fight, though, and the older woman comes out on top.

Eve feels compelled to tell Georges about the affair at her next visit, with most unexpected results. Far from being jealous or angry, the imprisoned man proposes a bargain that could work out to everybodyís advantage. Heís been plotting a breakout with one of the orderlies, but the plan always falls apart as soon as they get to thinking about how to proceed once theyíre on the far side of the asylum wall. If Eve and Jeff would agree to meet Georges immediately after the escape, and drive him to the docks in Marseilles, then heíll let bygones be bygones as regards the whole cheating thing. Georges would then telegram Eve as soon as he had himself more or less permanently situated, so that Annette would know where to find him. Jeffís reaction to hearing of said proposal comes as almost as big a shock as the scheme itself; he is, if anything, more enthusiastic about it than Eve.

Assisting the breakout proves to be every bit as good an idea as it sounds. The first hitch comes when Georges fails to meet Jeff and Eve at the rendezvous point. Eventually, Farrell concludes that something must have gone wrong on the prisonerís end, and he persuades Eve to split before somebody notices them loitering, and starts to get curious. When they get back to the car, though, they find a burly, scary-looking guy with sunglasses and a moustache (Donald Houston, from A Study in Terror and Clash of the Titans) sitting in the back seat. That would be Georges. The rest of the night passes without incident, but the conspirators are not in the clear yet, by any stretch of the imagination. The next day, they find themselves answering the questions of the entirely-too-sharp Inspector Etienne (George Pastell, from Konga and The Stranglers of Bombay), who mentions in passing that Beynat was not the only person connected to the asylum to go missingó the escapeeís accomplice on the staff has outed himself by pulling a vanishing act of his own. Farrell inadvertently solves that mystery himself on a grocery-shopping trip. When he pops open the trunk of Eveís car to load in their purchases, he finds a dead body already taking up all the cargo room. (Incidentally, I would never have guessed that a whole adult corpse could fit into the trunk of a turn-of-the-60ís Citroen!) Suddenly, he and Eve grasp the full magnitude of what theyíve done. And when a delivery man shows up at the inn with two industrial-size tanks of fresh oxyacetylene, the implications are clear to anybody who remembers what Beynat did to get himself locked up in the first place.

This being a Hammer mini-Hitchcock, itís inevitable that things are not what they seem from that mid-second-act vantage point. Thereís still a lot of betrayal and hoodwinking on the way. I donít want to say too much about the second half of the story, but I will observe (because itís important for how Maniac differs from its cousins) that the madness of Georges Beynat is but a red herring, cover for an eminently sane criminal conspiracy. Maniacís Psycho-like midpoint twist, meanwhile, is actually the crux of a double fake-out; its shower scene moment only seems to eliminate its Janet Leigh. That gives Maniac a unity of tone and purpose that Sangsterís other early-60ís thrillers lack, but that isnít always a point in this movieís favor. A few more disorienting revelations or whiplash-inducing subgenre shifts might have disguised the glaring unlikelihood of the twists and turns that it does take. Another important divergence from Scream of Fear and its other descendants concerns the setting, and the way that setting is used. It would be overstating the case to call Maniac a backwoods horror film, but it does convey a strong sense of the Camargue as an isolated, half-savage place where sensible civilized people tread only with great caution. That could scarcely be further removed from the genteel milieus in which the rest of the first-wave mini-Hitchcocks take place. Beyond that, Maniac is by far the least studio-bound Hammer film from this era that Iíve seen. It isnít just set in the far south of France, but was actually filmed thereó this is one of the few Hammer productions from the Bray Studios years where itís impossible to distract yourself from the story by playing Spot That Staircase. And the stone quarry where the climactic showdown occurs is the kind of location that would tempt Larry Cohen to write an entire script just for the excuse to use it. Finally, Maniac sets itself apart with a score that, so far as Iíve seen and can recall, is tonally unique in the Hammer catalogue. Peppy, jazzy, and insistent, itís more like a Krimi soundtrack than normative horror movie music, but itís deployed far more thoughtfully than Iím used to seeing in films from this era with jazz scores. Maniac has nothing like the unintentionally hilarious moment in The Fellowship of the Frog when the inspector is riding the bus to work through downtown Berlin, while the incidental music begs us to believe that his commute is the most exciting thing weíve ever seen.

Actually, I take that backó the score isnít quite the final thing. Maniac was also the first of the mini-Hitchcocks to resort to an old and by then mostly abandoned Hammer trick, importing a Hollywood B- or C-lister to increase overseas marketability. Kerwin Matthews seems a weird choice, but then so did Brian Donlevy and Forrest Tucker. In any case, this is certainly the best performance Iíve seen from Matthews. I gather that a caddish American bumming around Europe and getting into trouble was someone he could relate to more readily than Sinbad, Gulliver, or Jack the Giant-Killer. Iím similarly impressed with his costars, too, although in their cases I donít have much if any prior acquaintance on which basis to expect the contrary. Nadia Gray and Liliane Brousse are especially good with their charactersí creepy intergenerational competition over Jeff. Donald Houston is enjoyably slimy, and he and George Pastell share the best dialogue couplet in the whole film. (Youíll know it when you hear it.) Intriguingly, the paired lines come across as an acknowledgement of the absurdity into which psycho-horror in general, and Maniac in particular, is so often ready to descend. They suggest that Sangster understood how much he was trying to get away with, logically speaking, in this script and its predecessors, and in that regard it resembles the moment in Paranoiac when the duplicitous hero dismisses as no longer relevant a question about the plot that had been in the back of the audienceís mind since practically the moment he was introduced. Iím not sure the tactic works quite as well, though, in the context of this movie, which overall is plotted just realistically enough to make its departures from realism stand out unflatteringly.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact