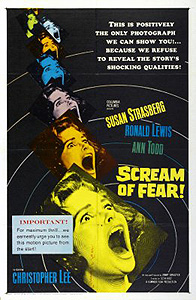

Scream of Fear/Taste of Fear (1961) ***

Scream of Fear/Taste of Fear (1961) ***

Perhaps the saddest thing about Hammer Film Productions’ slide into irrelevancy in the early 1970’s is that the hippy era was hardly the first time the studio faced a serious challenge to its domination of the international horror scene. Hammer had been in the horror business for only five years— and calling the shots within it for only three— when Psycho came along to suggest a totally different way of doing things. True, the first signpost in that direction was probably really Diabolique, but Hitchcock’s movie was the one that inspired the imitators for the most part, the Friday the 13th to Diabolique’s Black Christmas. In any case, Hammer’s response to Psycho poses a stark contrast to the bumbling, fumbling, and stumbling of a decade later; studio boss Michael Carreras looked at the Hitchcock film and replied in essence, “Shit, we can do that.” They really could, too, and beginning with 1961’s Scream of Fear, Hammer produced a steady stream of psychological horror films that would persist until the very eve of the studio’s period of final floundering. Given the point of the exercise— staking Hammer’s claim to an emergent subgenre while it was still profitably fresh in audiences’ minds— I find it very interesting how much Scream of Fear specifically owes to earlier forms of thriller. Despite the modern setting; the moody, monochrome cinematography substituting for Hammer’s usual flamboyant Pathecolor; and the conspicuous emulation of some of Hitchcock’s more famous tricks, Scream of Fear reminds me as much of Gaslight and The Woman in White as it does its primary inspiration.

A team of policemen dragging a lake in Switzerland pull up what they were presumably looking for— the dead body of a girl who will later be identified for us as Emily Frencham. Emily had been on holiday with her best friend, Penny Appleby (Susan Strasberg, from The Trip and The Legend of Hillbilly John), when for reasons that are shrouded in mystery, she left their suite at the chalet in the middle of the night and drowned herself. I’m actually getting well ahead of the movie by revealing even that much, but I’ll be breaking off this synopsis long before the subject of the drowned girl is raised again. I figure you deserve to know that there is a connection between the opening scene and the rest of the film, even if I’ll be keeping you in the dark regarding that connection’s true ramifications.

Some time later, Penny lands at the Nice-Cote d’Azure airport, where she expects to be met by her father (Fred Johnson, of Dr. Blood’s Coffin and Horror Hotel), a successful international businessman. This girl, by the way, has experienced far more than her share of hardship during her twenty years or thereabouts, despite the advantages conferred by her dad’s enormous wealth. First, she was paralyzed below the waist in a riding accident when she was a child. Then her parents split up, and her father moved away to the south of France; that was a decade ago, and Penny hasn’t seen him in person once in all that time. Then, a few months back, her mother died, leaving her effectively homeless and leading Emily to suggest the getaway to Switzerland. And of course we already know how that turned out, right? There’s more or less literally nothing left for Penny back in Britain, so she’s pulling up the stakes and moving in with her father and his second wife, Jane (Ann Todd, from Beware My Brethren and Things to Come). Contrary to the plan, however, Dad isn’t at the airport to collect her, having been called away on urgent business four days ago, and the task has been delegated to Bob the chauffeur (Ronald Lewis, of Mr. Sardonicus and Stop Me Before I Kill!). Fortunately, he seems a nice enough bloke, although he is visibly reluctant to answer many of Penny’s ten thousand questions about her stepmother, whom she has never met at all. Also, some information comes out during the drive to the Appleby mansion that puts the rather brittle and high-strung girl noticeably on edge. When Bob mentions Mr. Appleby’s physician, Dr. Gerrard (Christopher Lee), it’s the first Penny has heard of the fact that her father has been unwell. Furthermore, you sort of have to wonder— as Bob in fact does— what could have been so important as to make Appleby skip out on his daughter’s arrival if it’s normally a trial of his stamina just to leave the house. And last but not least, something about Bob’s phrasing and tone of voice when he introduces the subject of Gerrard seems to hint that the doctor’s relationship with his patient’s wife isn’t entirely kosher.

Be that as it may, Jane has clearly gone to some trouble to make Penny feel at home, regardless of the strained note that underlies all their interactions in that usual stepmother-stepdaughter way. She’s installed wheelchair ramps throughout the house wherever it was practical to do so. She’s converted Mr. Appleby’s study into a bedroom for Penny, refurbishing the place, while she was at it, in order to render it more cheerful and hospitable than it ever was during her husband’s occupancy. It’s one of the nicest rooms on the first floor, too, equipped with French doors that open out onto the courtyard bounded by the garage and the guest cottage, and offering ready access to the swimming pool— although the appeal of that last attraction would admittedly be more notional than practical in Penny’s case, even if the pool weren’t in desperate need of cleaning just now. Jane has even seen to it that there’s a recent photograph of Penny’s father in the room, to keep her vicarious company until such time as his unexplained business out of town is concluded. Yes, you’re quite right. It is disquietingly odd that even Jane professes not to know where her husband went, when he expects to return, or what, in even the vaguest sense, this errand of his is about.

Of course, that isn’t half as disquietingly odd as what happens to Penny on her first night at the mansion. Shortly before she intended to go to bed, Penny notices a faint glow through the windows of the guest cottage. No one’s supposed to be staying there, and to hear Jane tell it, the place is nothing but a glorified junk room these days, anyway. Curiosity getting the better of her, Penny wheels herself across the courtyard to take a look. The light, she discovers, is cast by a single candle, burning on the floor in front of the chair where her father is most unexpectedly sitting! Penny’s pleasure at the reunion is blunted a bit, though, when she notices that her old man is pretty obviously deader than disco. Her panicked flight back to the house to get help succeeds only in making things worse, for she cuts it a little too close on her way around the pool, pitching herself right into the murky, algae-choked water.

Luckily for Penny, Bob lives in an apartment above the garage, and he hears the commotion attendant upon her inadvertent late-night swim. He and Jane both take her raving about what she saw at the guest cottage for shock-induced delirium, however, and Penny spends the rest of the night under sedation courtesy of Dr. Gerrard. Nor does Jane alter her stance when Penny resumes going on about dead bodies in the cottage come morning. You see, although Jane may never have met her stepdaughter until yesterday afternoon, Mr. Appleby told her enough old stories to convince her that the girl is basically one big, tightly wound bundle of neuroses, phobias, and fixations. Even Penny herself admits that she has something of a history of letting her imagination run away with her, and now that Dr. Gerrard has had a chance to look her over, he goes so far as to wonder if maybe her paralysis could be psychosomatic. Superficially at least, it sounds like solid grounds for dismissing Penny’s experience last night as a dream or a subconsciously embellished trick of the light— or indeed as a straight-up hallucination, for that matter. After all, the door to the cottage is locked as always, and there’s certainly no corpse in there (Appleby’s or anyone else’s) when Jane opens it up for Penny’s inspection.

You know what is in the guest cottage, though? A slick of re-hardened candle wax, stuck to the floor exactly where you’d expect to find it based on Penny’s account. Bob doesn’t say anything about it while Jane is around to hear, but he brings the wax to Penny’s attention as soon as a chance to get her alone comes up. Clearly the chauffeur smells a rat (or at least a hamster or two), and believes that Penny saw something out of the ordinary last night, whether or not he’s prepared yet to accept that that something was Mr. Appleby’s corpse. Over the weeks to come, Bob and Penny grow increasingly close, and the more peculiar things she sees around the mansion (like the car that her father supposedly drove off in when he departed for his trip sitting in the garage, or a repeat performance from her dad’s body— both of which leave plenty of inconclusive physical evidence behind to hint that they really were there, even though they’ve vanished by the time Penny manages to summon witnesses to the scene), the more committed he becomes to helping her solve the mystery. The danger is that all signs seem to point toward Jane and Dr. Gerrard having killed Penny’s father, and a fair many of them also seem to point toward the culprits seeking to drive Penny mad, either to neutralize her as a witness against them or to secure their access to her share of Mr. Appleby’s estate once they’re ready to go public with his death. Obviously she and Bob had better find that body and present it to the authorities before the conspirators realize they’ve been found out.

Scream of Fear doesn’t demonstrate quite the same mastery of its subgenre as earlier Hammer productions demonstrated of gothic or sci-fi-inflected horror in the 1950’s, but it is competitive, on the whole, with any but the best of the similar movies that William Castle would make during the post-Psycho era. Susan Strasberg is one of 60’s psycho-horror’s better damsels in distress, Christopher Lee is wonderfully smarmy (who the hell knew that Lee could do smarm?) as the vaguely but palpably suspect doctor, and Ronald Lewis damn near walks off with the whole movie as a character who repeatedly shows us that we don’t know him nearly as well as we think we do. The already obligatory twist lacks the conceptual elegance of Psycho’s or Homicidal’s, and it suffers from the same expository club-footedness that compromised the conclusion to the former film, but it’s both satisfyingly unexpected and weirdly plausible by the emerging standards of the genre. Director Seth Holt got his start as an editor, and that background shows in the unexpectedly crisp pacing that he brings to this low-key and rather talky picture. Nor should that be taken to imply that Scream of Fear is without the sort of visual impact that one associates more with cinematographer directors; in particular, the scene in which Bob goes hunting for Mr. Appleby’s body in the befouled swimming pool is nearly as effective as the similar sequence in Dementia 13 (which it may indeed have influenced). But as I implied earlier, what intrigues me most about Scream of Fear is its version of the edgy conservatism I’ve identified elsewhere as a recurring Hammer trait. In Hammer’s more famous gothic horror movies, the phenomenon manifests itself via controversy-courting takes on old subject matter— thinning the veil of metaphor over the sexuality in vampire stories, wallowing in the gore and cruelty attendant upon mad science, and so forth. With Scream of Fear, however, what we have is antique content injected into a thoroughly modern form. The villains’ efforts to conceal a crime by driving to madness the one woman who might expose it is straight out of Gaslight, while the central premise of a fragile and vulnerable girl delivered into the hands of evil relatives by the death of a parent is at least as old as Matthew Lewis’s The Monk. For the most part, Jimmy Sangster simply wrote the sort of horror story he already knew, transposing it into a more modern and prosaic setting. It has the salutary effect of preserving the essential Hammer-ness of the proceedings in an almost subliminal way, even as Scream of Fear bears the studio’s traditional horror output scarcely any outward resemblance.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact