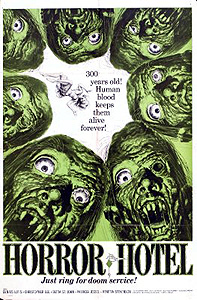

Horror Hotel/City of the Dead (1960) ***½

Horror Hotel/City of the Dead (1960) ***½

You know the old saying about turnabout being fair play? Well how’s this for an example? Ever since there was such a thing as American horror cinema, the makers of US horror films have been using Great Britain as a setting for their movies. With its great antiquity in comparison to the United States, its continued adherence to the form if not the substance of medieval social structures, and its marked propensity for being blanketed in clouds and fog, Britain seems a far better locale for tales of gothic horror than just about any place you’ll find in the Americas, while the close cultural affinity between the two nations makes the Isles much easier for Hollywood to fake than, say, Russia or China or Morocco. The Brits, on the other hand, have been much less eager to set their horror films on this side of the pond (most of the Hammer gothics, for instance, take place in Continental Europe), and those few British horror films that are set in North America generally have a strong streak of sci-fi running through them— Fiend Without a Face and First Man into Space, for example. But when the fledgling Amicus Productions made their first foray into gothic horror, what do you suppose they did? That’s right— they set it in a rural village in Massachusetts! Perhaps this isn’t quite as big a shock as it looks, however. Though he received no screenwriting credit, the story from which Horror Hotel’s script grew was written by Amicus boss Milton Subotsky, who was an American expatriate, and who had brought a decidedly American flavor to the studio’s earliest projects. I mean, what? Did you think the British would ever have made rock and roll movies during the 50’s if left to their own devices? Nevertheless, by the time screenwriter George Baxt and director John Moxey got through with it, Horror Hotel was as characteristically English in tone as anything being put out by their rivals over at Hammer.

In what is either a conscious crib from Black Sunday or a truly amazing coincidence, Horror Hotel begins with the Puritan leadership of Whitewood, Massachusetts, arresting and condemning a suspected witch named Elizabeth Selwyn (Patricia Jessel) to the stake. Selwyn is defiant to the last, and if meteorological conditions at the moment of her execution are any indication, her relationship with the powers of darkness is close enough to give that defiance some weight. While the village headmen put torches to the kindling piled up around Elizabeth, her lover, Jethro Keane (The Haunting’s Valentine Dyall), mutters a prayer to Lucifer under his breath. Suddenly, the sky darkens and a storm brews up, adding a note of panic to the villagers’ voices as they chant, “Burn, witch! Burn, witch! Burn, burn, burn!”

Jump forward some 260 years. History professor Alan Driscoll (Christopher Lee) regales his pupils with the story of Elizabeth Selwyn’s execution on the last day of classes before a two-week break, going on to mention that some years after her death, there were a number of reports of a woman meeting the supposed witch’s description in the countryside around Whitewood. Most of the students exhibit no interest in the tale one way or the other, but Bill Maitland (Tom Naylor) and Nan Barlow (Venitia Stevenson, from Island of Lost Women) both react quite strongly. Maitland all but heckles Driscoll’s lecture, unable to see any point in studying the murderous superstitions of his distant ancestors; one wonders what he’s doing in a college history class in the first place. Barlow, however, is riveted. In fact, she hatches on the spot a scheme to use her upcoming vacation for a trip to New England to do original research on the subject of Colonial-era witch panics. Driscoll is happy to support her efforts, giving her both directions to Whitewood itself and the name of an inn in town where she ought to be able to stay during her visit. Nan’s idea doesn’t sit well with Bill— who, unaccountably, is the girl’s boyfriend— or with her brother, a young associate science professor named Dick Barlow (Swords of Sherwood Forest’s Dennis Lotis), but Nan’s mind is made up. She’ll see both Dick and Bill at the end of the holiday, when the three of them will attend a birthday party for her cousin, Sue (Maxine Holden), but until then, it’s Whitewood and witches for Nan.

Evidently there are some things that never change no matter which continent you go to. Be they in Europe, the Far East, or just boring old rural Massachusetts, tiny little out-of-the-way villages are always trouble for outsiders, full to overflowing with suspicious natives, sinister secrets, and subterranean supernatural evil. On the way to Whitewood, Nan must of course ask for directional clarification from a hillbilly gas station attendant, who tries to warn her against proceeding on to her destination: “Not many God-fearing people go into Whitewood these days, miss…” Then she picks up a disappearing hitchhiker. She doesn’t recognize the old weirdo as Jethro Keane, but we sure do. The capper to the whole business? The owner of the Raven’s Inn, Mrs. Newlys, looks exactly like Elizabeth Selwyn, of whose name hers is an obvious anagram. Needless to say, there’s a reason Mrs. Newlys is so keen to prevent her mute chambermaid, Lottie (Ann Beach), from communicating with Nan in private.

Nan goes out to see the town shortly after her arrival, at which point she is stared down by the usual creepy villagers and has the requisite encounter with the crusty old preacher (X: The Unknown’s Norman MacCowan), who insists that she leave Whitewood while steadfastly refusing to give her the sort of explanations that might lead a stranger such as herself to conclude that listening to him was a good idea. In fact, the one person Nan meets in Whitewood who doesn’t go out of their way to give her the creeps is the preacher’s granddaughter, Patricia Russell (Betta St. John, from Corridors of Blood and The Saracen Blade), who runs the little antique shop right next door to the ruined church where her grandfather spends most of his time. One assumes that Patricia’s decency is due entirely to her short tenure in town; up until her grandmother’s death a few weeks back, she hadn’t set foot in Whitewood since she was a small child. In fact, so friendly and solicitous is Patricia that she assists Nan in finding sources for the research she has come to carry out, presenting the student with an ancient book from her grandma’s library, entitled A Treatise on Devil-Worship in New England. Nan is naturally unable to afford the old tome, but Patricia agrees to lend it to her for the duration of her stay.

Her stay, incidentally, proves to be rather shorter than she intended— or perhaps longer, depending on how her killers dispose of the body once they finish with her. Among the fascinating details that Nan gleans from her borrowed book is that the witches’ coven of which Elizabeth Selwyn was supposed to have been a member used to perform human sacrifices on the night of Candlemas Eve, and that they designated the person to be sacrificed by replacing an object of value to that person with a dead bird and a sprig of woodbine. And right about the time that she reads all that, certain parallels begin showing up in her own life. The locket which Bill gave her as a present some time ago disappears, and somebody stashes a sparrow carcass in her dresser drawer. And while Nan wouldn’t know a sprig of woodbine if you shoved one up her ass, I think it’s fairly safe to say that we can properly identify the leafy little twig that somebody tacks to the door of her room while she’s caught up in her work. Nor will we be surprised to learn that Candlemas Eve is right around the corner. Meanwhile, somebody keeps chanting down in the cellar below Nan’s room, even though Mrs. Newlys swears that that part of the basement was filled in long ago in order to strengthen the inn’s foundation. When Nan’s curiosity finally gets the better of her, and she pries open the sealed trap door beneath the carpet in her room, she finds not just a cellar, but an entire network of catacombs down there. It is here that Nan meets her end, blundering upon the scene of a Satanic ceremony at just the perfect time for her to take her appointed place on the altar.

Two weeks later, Bill and Dick have begun to worry about Nan. Neither one has heard from her since the day she left for Whitewood, and when she fails to appear at Cousin Sue’s birthday party, they both feel certain that something is wrong. At Maitland’s urging, Barlow calls the police, and has them check out the Raven’s Inn. The detectives find no trace of Nan. Dick tries Professor Driscoll next, believing that the man who sent Nan to Whitewood to begin with might be able to tell him something about what goes on there. If only Barlow could see what his colleague had been doing before he arrived: dressing up in a curiously embroidered cloak and offering the blood of a white dove to the Prince of Darkness! Driscoll, unsurprisingly, is no help at all, and it isn’t until Barlow and Maitland get in touch with Patricia Russell that they start to put the pieces together. Of course, by then, the next big holiday in the Satanic liturgical calendar has rolled around, and Patricia has been chosen by the Whitewood coven as their next human sacrifice.

The main thing that will strike you about Horror Hotel once you’re about halfway into it is the close structural similarity it bears to Psycho. Nan Barlow’s death nearly an hour into the movie strongly suggests the fate of Janet Leigh’s character in the Hitchcock film, and has a similar psychological effect. As with the Black Sunday parallel in the opening scene, I’m really not sure whether we’re looking at deliberate copying or just a startling coincidence. All three movies were released in 1960, but I don’t think Black Sunday made it to England until 1961, and I know Horror Hotel beat Psycho to the British screen by most of a year. The question is whether Subotsky got to work on the story before word of the other two films reached him from their countries of origin.

But even if Subotsky, Moxey, and Baxt really were ripping ideas off left and right, what they made of those ideas was something entirely their own. Horror Hotel is a highly effective film, and it’s amazing to me how aggressively it deals with its subject matter. Remember that movies about devil worshipers were strongly frowned upon by the Britsh Board of Film Censors during the 1960’s; it took Hammer four years to get a green light from the BBFC to shoot The Devil Rides Out. Perhaps the setting played a part in allaying the board’s usual worries— certainly that organization had a long history of paroxysms at the thought of Jolly Old England serving as a hotbed of supernatural horror, so maybe Amicus got off easier by using Massachusetts instead. In any case, we might justly feel grateful that the BBFC didn’t raise enough of a fuss to dissuade the studio from going ahead with Horror Hotel. It has practically everything anyone could ask for from a 1960’s gothic— obsessively careful production design, beautiful and moody cinematography, radiantly lovely lead actresses in two unexpectedly forceful roles, an enjoyable if minor villainous turn from Christopher Lee. It even features a much stronger climax than was usual for movies of its time and type, and I have absolutely no idea how the BBFC let Amicus get away with this movie’s parting shot. Best of all, Horror Hotel offers a take on 60’s Brit-horror that is much farther afield from the signature Hammer style than most of its studio’s better-known horror films would venture. Die-hard Hammerhead though I am, I greatly appreciate the chance to hear the tune sung in a distinctly different voice.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact