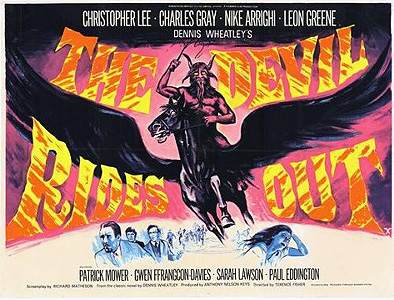

The Devil Rides Out/The Devil's Bride (1968) -***

The Devil Rides Out/The Devil's Bride (1968) -***

Though I have nothing but respect for Christopher Lee as an actor, I must admit that his taste in literature is somewhat questionable. Lee was both a close friend of author Dennis Wheatley, and a great fan of that writer’s often hilariously earnest novels of black magic and Satanism. As early as 1964, Lee convinced Hammer Film Productions boss Anthony Hinds that Wheatley’s The Devil Rides Out would make an excellent basis for a movie, but production was held up until late 1967 by the revulsion of the British censor board at anything dealing so directly with devil worship. The movie that finally saw release is a curious mixture of the compelling and the ridiculous, in which a few almost-brilliant performances and vast amounts of apparently authentic occult lore rub shoulders uneasily with frequently ludicrous dialogue, special effects that overreach themselves disastrously, and pacing that is far too brisk for the story to keep up with.

It isn’t often you see an English horror movie that goes too fast. But from the moment Duc Nicholas de Richleau (Christopher Lee) and Rex Van Ryn (Leon Greene, from the 1980 version of Flash Gordon) realize that their third friend, Simon Aron (Patrick Mower, of Incense for the Damned and Cry of the Banshee), hasn’t shown up for a planned reunion between the long-separated trio, there’s just barely enough downtime in which to explain how or why any of the strange goings-on that ensue are happening. As soon as de Richleau and Van Ryn realize that Aron isn’t coming, they head over to the big-ass mansion the missing gentleman recently purchased, where the duc immediately discerns that something is wrong. Simon is throwing a party, the guest list for which consists of all thirteen members of the astronomical society he has recently joined. He is obviously disturbed by his friends’ arrival, and several of the guests express some dismay that there are now two people too many in the house for whatever it is they planned to do later. When Mocata (Charles Gray, from The Beast Must Die and The Rocky Horror Picture Show), the head of the astronomy club, comes downstairs, de Richleau whispers to Van Ryn that “we’re about to be asked to leave,” and sure enough, Simon starts ushering them toward the door just moments later. The duc stalls by asking to have a look at Aron’s telescope (the mansion has a big, obvious observatory in the attic), and it is then that he finds the final confirmation of his suspicions. The charts on the walls of the observatory are not astronomical but astrological, and the floor is dominated by a mosaic of Oswald Wirth’s famous goat-head-and-pentagram motif. What’s more, a nearby closet contains a wicker basket in which a couple of chickens— the same pairing of a white hen and a black rooster recommended as sacrificial animals by Aleister Crowley— are imprisoned. “Astronomical society” my ass; Simon Aron has gone and joined up with a Satanic cult!

This is where Nicholas de Richleau springs into full-scale deprogrammer mode. When Aron won’t listen to de Richleau’s exhortations to dissociate himself from Mocata’s coven, the duc actually punches his young friend out and shanghais him from his own house! Back at Chez de Richleau, Nicholas hypnotizes Simon and sends him off to bed before taking on the arduous task of explaining to Rex just what in the hell is going on. But Mocata has a stronger hold on Simon than de Richleau has given him credit for. While Rex and his host are discussing the Powers of Darkness, Mocata psychically induces Simon to escape out the window of Nicholas’s bedroom and return to him. This poses an even bigger problem for his would-be rescuers than it might seem, in that Simon doesn’t go back to his mansion (our heroes nearly lose their souls to one of Mocata’s demonic underlings while finding this out), and neither de Richleau nor Van Ryn has any idea where Mocata might live.

Rex has an idea that might get them around that obstacle, though. At Simon’s party, he met a young woman named Tanith (Nike Arrighi), whom he’s certain he recognizes from somewhere. Thinking hard about when and where that previous encounter might have been, Van Ryn is eventually able to track Tanith down and ask her out. The idea here is that their date will serve as a pretext for extracting information about Mocata and his followers that could help de Richleau figure out where Simon is being held. While “stealthily” interrogating her, Rex discovers that Tanith isn’t yet a full-fledged member of the coven. Like Simon, she is still awaiting her Satanic baptism, and in fact both of them are supposed to be inducted in the same ceremony. When he hears that, Rex tries to pull the same trick on Tanith that Nicholas pulled on Simon the night before, driving her against her will to the home of his friends, Richard (Paul Eddington) and Marie (Sarah Lawson, from “The Trollenberg Terror” and Island of the Burning Doomed). Tanith proves just as slippery as Aron, however, and speeds off in Rex’s car the moment he gets out of it to greet the couple. The resulting car chase (and let me tell you, motor vehicle chases sure do look funny when they use 1920’s automobiles) ends with Tanith making a nearly complete escape; a little magical intervention from Mocata causes Van Ryn to wrap Richard’s roadster around a tree. The only reason the man is able to catch back up with his quarry is because he fortuitously encounters another member of the cult on the road, and is able to trail her to the warlock’s house.

That evening’s Satanic ceremony is, for me, one of the highlights of the movie— but not for any of the reasons director Terrence Fisher or screenwriter Richard Matheson would have intended. For one thing, this is just about the most restrained demoniacal orgy you’ll ever lay eyes on. (Nikolas Schreck, writing in The Satanic Screen, sums it up beautifully: “Although Hammer originally planned a more appropriately erotic bacchanal, the prudish censor insisted that proper British Satanists must keep all their clothes on whilst orgying.”) But equally counterproductive is the fact that Satan puts in a personal appearance, in the form of a most unimpressive goat-headed man. And lest you try to salvage the situation by saying the goat-man is just another minor demon, the eavesdropping Duc de Richleau deprives you of that option by exclaiming, “The Goat of Mendes— the Devil himself!” Surely the Prince of Darkness has better things to do with his time than attend the baptism of a pair of malnourished English cultists! Then in a turn of events that ends up making Mocata, his cult, and their infernal master look like far less of a threat than anyone concerned would like us to believe, the Duc de Richleau and his trusty sidekick banish the Lord of the Flies by tossing a chintzy little cross at him, and proceed to disrupt the baptism ceremony quite effectively by driving a car through it and making off once more with the two inductees.

Mocata wants both Simon and Tanith back, of course, and he’ll stop at nothing (well, nothing a British special effects department could afford, at least) to reclaim them. While de Richleau is out, Mocata comes calling on Marie (her house has been pressed into service as the base of de Richleau’s anti-cult operations), and nearly succeeds in using his powers of mind control to undo all of the duc’s progress. First he hypnotizes Marie into revealing that his quarry is indeed being hidden in the guest rooms upstairs, then he tries to force his lapsed proteges to kill Richard and Van Ryn, who have been standing guard over them. Only a timely interruption from Marie’s daughter, Peggy (Rosalyn Landor), staves off the sorcerer’s victory, breaking his concentration and freeing all three people from Mocata’s mental hold. Satan’s disciple withdraws at that point, but the battle is far from over. That night, when the setting of the sun brings his power to its highest point, Mocata sends a formidable roster of demonic forces to capture Simon and Tanith, including a Peggy doppelganger, a giant spider that Bert I. Gordon would have been proud to call his own, and a singularly disappointing Angel of Death. But Mocata has greatly underestimated his opponents, for Nicholas de Richleau’s white magic proves to be every bit as powerful as the warlock’s black.

The first item in the credit column of The Devil Rides Out’s quality ledger is, unsurprisingly, Christopher Lee. Lee makes the most of his underwritten and overblown character, and invests yet another tacky movie with considerably more dignity and authority than it really deserves. Charles Gray’s Mocata is almost as well realized, but I still couldn’t help seeing him first and foremost as that useless criminologist from The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Audience participation catcalls associated with Gray’s scenes from that movie kept shooting through my head whenever the evil magician was onscreen. The most interesting of The Devil Rides Out’s good points, however, is the unusually scrupulous portrayal of Mocata’s cult and its beliefs, rituals, and observances. On the one hand, such treatment ought to be expected, given that Dennis Wheatley was personally acquainted with Aleister Crowley, and apparently made much use of him as a source for the magical lore in the novel on which this movie was based. But at the same time, filmmakers all over the world have a long history of dumbing down the more complex elements of books they adapt to the screen, so there would be little reason to expect much of Wheatley’s painstakingly researched background material to make it into the finished film. That so much of it did is a major point in The Devil Rides Out’s favor.

Unfortunately, all that ends up being virtually drowned out by silliness. The tawdry monster effects— the giant spider, the rather shabby Satan, the absolutely hopeless Angel of Death— are sure to attract the most attention in this department, but really they do only a small share of the damage. Far more significant is the sloppy quality of the writing. De Richleau catches on to Simon’s dabbling in Satanism so quickly that all but the most uncritical viewers are likely to join Rex Van Ryn in his defiant skepticism. It doesn’t get any easier to believe when de Richleau spends the rest of the movie pulling out one tidbit of occult knowledge after another. Matters are then made even worse by the fact that it is never explained, or even hinted at, how and why Duc Nicholas came to acquire his esoteric education. No reason is ever offered for Tanith’s attraction to Mocata’s cult, or for her eventual apostasy from it either. And I’m quite certain that not a single one of my friends would be as eager to accommodate me as Richard and Marie are here if I showed up on their doorstep one day with a pair of semi-conscious hostages and a cock-and-bull story about devil-cults and evil magicians. I think the real problem stems from something I’ve only recently noticed about Richard Matheson as a screenwriter. When adapting other authors’ works to the screen, Matheson is remarkably adept at preserving the spirit of their writing, even when he distorts their plots, characters, and dialogue beyond all recognition. When he’s working from something written by a good or at least decent author— Edgar Allan Poe, for instance— this ability of Matheson’s is a tremendous asset. But when his source material comes from a lousy writer like Dennis Wheatly, it is a distinct liability. Wheatley apparently firmly believed in the literal reality of Satan, and he took the devil’s self-proclaimed disciples entirely seriously. Indeed, he was in the habit of prefacing his novels with warnings about the grave spiritual danger that a person placed themselves in simply by reading them! The result is that it is very difficult to take Wheatley seriously, and it is to the detriment of The Devil Rides Out that Matheson’s script carries so much of that quality over to the film, though it remains tremendously entertaining in spite of itself.

Thanks to Cliffie for supplying me with my copy of this movie.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact