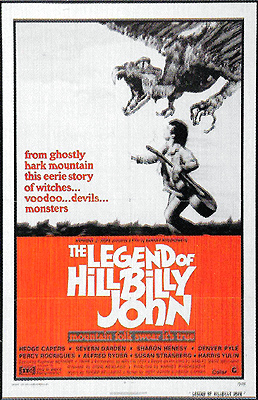

The Legend of Hillbilly John (1973) **½

The Legend of Hillbilly John (1973) **½

When I was a sophomore in college, I encountered two books that completely changed the way I approached reading fiction: Stephen King’s rambling, discursive, cross-media history of the horror genre, Danse Macabre, and David G. Hartwell’s monumental short story anthology, The Dark Descent. Up to then, I’d always been content to read very casually, accepting whatever happened to be on offer at the library or the local Crown Books. In practice, that tended to mean current authors and books that were either new or perennially popular. It also meant drawing few if any connections between writers, since mass-market paperbacks of books too new or too disreputable to be issued by a “classics” imprint (and seriously— what’s more disreputable than horror fiction?) didn’t typically come with introductions discussing their creators’ influences. Danse Macabre and The Dark Descent between them gave me a framework in which to place the books I’d been reading, introduced me to scads of authors I’d never heard of before, and most of all pushed me to seek out specific works, regardless of whether they were still in print. In a roundabout way, they also introduced me to the pleasures of the used book store, the public library’s sell-off racks, and the thrift store book department, for only in such places could I find the relatively esoteric stuff that I suddenly craved. One of those previously unknown writers I now found myself in search of was Manly Wade Wellman, a mid-century shudder-pulp luminary who used the folklore and superstition of southern Appalachia as raw material for some of the most memorable and distinctive horror stories I’ve ever read.

Like a lot of people in his corner of the business, Wellman used recurring characters to keep the magazines buying his tales and the fans reading them. During the 30’s and 40’s, when Weird Tales dominated the market for dark fantasy, Wellman had three ongoing series in the works, detailing the adventures of spook-busting heroes John Thunstone, Professor Nathan Enderby, and Judge Keith Pursuivant. But the character he’s best remembered for today was a later creation, not appearing until the early 50’s. Wellman never called him anything more than “John,” but to his fans, he’s variously known as Silver John, Hillbilly John, or John the Balladeer. Each of the three handles reveals something significant about him: the silver strings of his guitar, which have talismanic power against his supernatural foes; the Appalachian setting of all the tales concerning him; and his motive for wandering the remotest paths of the mountains, collecting the lore and music of isolated communities, and using the secret wisdom therein to battle the dark forces that seem to hold sway in all the most truly backward glens and valleys. I know of nothing else quite like the Silver John stories. They have an incredibly vivid sense of place, a strong and unmistakable authorial voice, and an approach to the subjects of monsters and magic that feels both completely fresh and ancient beyond mortal memory. They deserve to be far better known than they are, but they fall so far outside the stereotyped conceptions of fantasy and horror fiction that I’m only a little surprised that they’re not. What surprised me much more, when I learned of it via The Bad Movie Report, was that there had been a Silver John movie. The Legend of Hillbilly John doesn’t really capture the power or unique sensibility of Manly Wade Wellman’s writing, but it’s worth a look as one of the film industry’s stranger attempts to woo the hippy counterculture.

Now despite the existence of several novels written later in Wellman’s career, John the Balladeer has always been a short story character first and foremost. The Legend of Hillbilly John attempts to keep faith with that history by means of a narrative structure so episodic that the film might usefully be thought of as an anthology in which the same core characters figure in every segment. There’s even an anthology-like framing sequence in which a well-dowser called Mr. Marduke (Severn Darden, from Werewolves on Wheels and Conquest of the Planet of the Apes) holds forth on the role of the Devil in Appalachian culture, and shows us the worksite for the construction of a new interstate highway to illustrate how endangered the hillbilly lifestyle is today. That sets the stage for the first story, in which a young man named John (39th-string folk singer Hedges Capers) learns that his grandfather— also named John (Denver Pyle, of Escape to Witch Mountain and The Flying Saucer)— has vowed to sing the Defy.

I gather that singing the Defy is a bit like challenging the Devil to an MC battle. I can’t tell you anything about the details, though, because on this occasion, Satan drops the mike so hard the film breaks. All we see of the confrontation is a grizzled old man strumming his guitar and croaking out the coal-country equivalent to “Old Nick’s mama’s so fat…” for a minute or so, and then suddenly it’s all white screen and sprocket holes. Everybody in the whole valley— John the Younger included— had tried to talk Grandpappy John out of it, but the contrary old bastard was sure that he had an angle. Knowing that Evil fears nothing more than “true silver,” Grandpappy melted down five shiny new Kennedy half-dollars to make a set of demon-repellant strings for his guitar. The numismatists among you will already see the problem. The Kennedy half-dollar was introduced in 1964, just one year before the Coinage Act of 1965 reduced the silver content of 50-cent pieces to 40%— and since 1971, circulating American coinage of any denomination has contained no silver at all. Evil, or so we may surmise, doesn’t fear true cupro-nickel alloy one little bit. In the aftermath, John the Younger decides to take up where Grandpappy left off, to which end he hires Marduke to dowse him up some old Spanish pieces of eight in exchange for the only thing of value he can practicably offer— dinner at his house, including the salt pork that passes for fine dining in these parts. The Spaniards having been deadly serious about stealing silver from the Incas, there’s no question about those coins yielding guitar strings of Defying-grade purity.

John also has the good sense to work his way up to a proper Defy, honing his evil-fighting skills on somewhat easier targets first. His initial opponent is no demon, nor even a witch in service to same, but merely an exceptionally complete asshole. People in the next valley over are having trouble with their undertaker, Zebulon Yandro (Harris Yulin, of Bad Dreams and The Believers), although it’s unclear just what form that trouble takes. In any case, it’s recorded in song around yonder that Zeb’s grandfather, Yoris— an even greedier son of a bitch than his descendant— once got himself mixed up with a witch named Polly Wiltse, who offered him an incalculable fortune in gold if he would be her lover for just one year. According to the songs, Yoris took the gold and ran, leaving Polly alone on her mountain to witch up more of the stuff in the vain hope of luring him back. Zebulon knows those songs, too, and he’s intrigued when John tells him of a man he once met who claimed to have seen Polly’s gold with his own eyes. The mountain Polly supposedly haunts is on the Yandro family property, which would make Zeb the legal owner of the treasure if it really did exist. Inevitably, Yandro has John lead him to the place that midnight, when the songs all agree Polly comes out of hiding. Sure enough, they meet a lovely young woman (Susan Strasberg, from Scream of Fear and Hauser’s Memory) who claims to be the witch herself, preserved by her magic exactly as she was in Yoris Yandro’s time 75 years ago. Polly is unimpressed by Zebulon’s claim to ownership of her gold, since his land never gave it forth in the first place. But since Zeb is the spitting image of his granddaddy, she’ll be happy to extend to him the same bargain. Zebulon takes some persuading, but eventually concludes that the witch’s hoard is worth the hassle of taking a year off from the grave-digging business. And because it was John who made this “reunion” possible, Polly favors him with the information that the next station of his march to destiny lies in a place called Hark Mountain. Let’s just say that John winds up much happier with the outcome of the night’s adventures than Yandro. Bargaining with witches is hazardous enough, even when you don’t try to cheat them…

Hark Mountain turns out to be the site of a strip-mining operation for anthracite coal. John’s discovery of a girl’s body petrified into the same material under a drift of rubble indicates that it’s the site of something even more unsavory as well. A moment after finding the coal girl, he is attacked by the aptly named Ugly Bird, a creature which suggests what Sam Katzman probably wanted the monster in The Giant Claw to look like. John shouldn’t stand a chance against the feathered abomination, but Ugly Bird breaks off its dive every time it comes within talon’s reach of his guitar. After the horrid thing finally gives up and goes away, a quick experiment with one of its shed feathers confirms the main reason why; more than a second’s contact with the instrument’s silver strings causes the feather to burst into flames. Soon thereafter, John meets the Ugly Bird’s master, a warlock by the name of O. J. Onselm (Alfred Ryder)— who happens also to be the owner of the strip-mine, and wannabe owner of all the rest of the land around Hark Mountain. The previous village’s complaint with Zebulon Yandro might have been vaguely defined, but between Ugly Bird and the anthracite girl, any fool can see why Onselm has his neighbors terrified. Indeed, they’re frightened enough of the witch-man to breach the usually inviolable Appalachian norm of hospitality toward travelers when John comes through. Hell, they go so far as to take Onselm’s side once the inevitable battle between him and John begins, and so strong is the habit of their fear that they transfer it to their deliverer after John narrowly emerges victorious.

John’s third clash against the forces of darkness occurs at a crooked cotton plantation, where the black sharecroppers live in a state barely distinguishable from the slavery of their ancestors. Surprisingly, their chief oppressor is a black man himself, although viewers well versed in the intricacies of unreconstructed Southern racism will note that Captain Lajoie H. Desplaines IV (Percy Rodrigues, from The Astral Factor and A Carol for Another Christmas) is both lighter-skinned and more Caucasoid-featured than the wretches who toil in his fields. Such viewers will also recognize that Desplaines must be a dangerous man indeed to command the unquestioning obedience of the Boss Hogg type he’s got reading (or more to the point, misreading) the scale at the weighing station for him. As we shall soon see, the captain is a powerful Haitian witch doctor, much more formidable than Onselm and his giant turkey. John will have an ally in this fight, however, for among the put-upon field hands in a tough old man called Uncle Anansi (Chester Jones, of Dark Intruder and The Leech Woman), who’s as much of a Defier by temperament as the balladeer. That’s Anansi as in Anansi the Spider, West Africa’s foremost trickster spirit, and to hear Desplaines talk about the old troublemaker, I don’t think the name is a coincidence.

In between John’s big battles (the biggest of all being not shown, but rather implied by the charmingly naïve shot on which the movie ends), he faces a much subtler, but ultimately more significant struggle. During each lull, he is tempted by the siren song of a normal life. That temptation is personified by three figures: John’s dog, Honor Hound; his girlfriend, Lily (Sharon Henesy); and Marduke the dowser. Honor Hound, as befits his species, makes the crudest and most direct appeal, cowering before the unknown terrors of Hark Mountain just as soon as he’s sniffed out the trail leading to it. It’s a scary world John’s messing around with, the dog reminds him, and nobody’s forcing him to do it but himself. Lily, meanwhile, plays on a different set of emotions. She gets lonely while John is off fighting evil, and she rightly worries about his safety. Beyond that, she’s the voice of conventionality, asking, in effect, why it can’t be somebody else’s job to set avaricious jerks up with jealous witches and to smack Ugly Birds upside the head with silver-strung guitars. In fact, Lilly starts in on that line the second John shows her his pieces of eight, fantasizing about the domestic goods that the antique coins could buy them. Marduke’s temptations are the most interesting, not least because his motives are so ambiguous. He happens to come along whenever John needs help, and he always comes equipped to provide exactly the kind of help John requires— even the supernatural variety. Marduke’s aid, though, is always accompanied by a test of John’s resolve. When he divines the location of the coins, he mentions that there’s a much bigger cache of them buried deep down— deep enough that to get at them would mean putting off the Defying quest indefinitely. Later, after the Ugly Bird incident, he sets John up with a new guitar, but also cautions him to expect very little appreciation from the people he saves. Defying evil means stirring shit up, and most folks would sooner tolerate the Devil than a shit-stirrer.

You’ll notice that these are very much the kinds of things that the Devil himself would say. Meanwhile, it’s worth observing that Marduke has a donkey named Asmodeus, and that Grandpappy John’s Defy goes sour immediately after Marduke joins the crowd of onlookers— from a direction that visually implies opposition to the Defier’s designs. Consider also that Marduke eventually all but tells Lily that he’s really an avatar of the Eastern Semitic deity Marduk. It was common for other people’s gods to be reinterpreted as demons once Judaism completed its evolution from monolatry to monotheism, so Marduke might be confessing to a great deal more than the face value of his words would indicate. On the other hand, many of Marduk’s mythological exploits have parallels in myths of the Canaanite chief god, El— and far from becoming a demon, El was absorbed into Yahweh once the Jews had lived a few generations in the Promised Land, much as the Romans came to identify their Jupiter with the Greek Zeus. Perhaps, then, Marduke isn’t Satan, but God himself, in which case we should interpret his talks with John not as temptations, but as tests of faith. After all, whatever we call them, the result is the same. John turns away from the simple life to embrace his role as Defier.

It should be clear by now that The Legend of Hillbilly John is an exceedingly smart movie. Unfortunately, it’s also a muddled and disorganized one, without much focus and with only the vaguest through-line. Beyond that, it’s likely to annoy fans of the source material, because the film’s John is very different from Manly Wade Wellman’s. It stands to reason that a movie aimed primarily at hippies would valorize childlike innocence and simplicity, since the counterculture put great stock in those qualities as well, at least in theory. The Legend of Hillbilly John takes it much too far, however. Between Melvin Levy’s dialogue and Hedges Capers’s untutored performance, the movie turns Wellman’s sharp, resourceful hero into something perilously close to a magic retard— a Devil-defying Forrest Gump. The bid for hippy appeal is also evidenced to the picture’s disadvantage in the songs (a film about a wandering balladeer naturally features a lot of those), which are mostly folk music in the Joan Baez sense, rather than the Fiddlin’ John Carson sense. The impressive exception is Grandpappy John’s Defy tune, which truly does sound like it was handed down from one coal-country redneck singer to the next for a dozen generations, even though it was written especially for the film. Another questionable choice concerns the temporal setting. Wellman’s stories were themselves pretty vague about when they’re supposed to take place, but the overwhelming impression is of a time before the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Rural Electric Cooperatives, or the Interstate Highway System, when Appalachia was effectively a world unto itself, cut off from the rest of American culture by a geography as yet untamed by 20th-century technology. The Legend of Hillbilly John preserves that feel for the most part— but then shoehorns a couple of flower children into the middle of things, and keeps taking time out to tell us in other ways that no, this is definitely 1973. It’s almost as if every settlement John visits is one of those towns out of time that “The Twilight Zone” loved so much.

That said, if you can approach The Legend of Hillbilly John not as a Sliver John movie, but rather as a bunch of weird stuff that happens to this kid from Appalachia, it makes for fairly rewarding viewing. It’s full of thought-provoking mysteries and ambiguities, for which the lack of resolution feels purposeful instead of lazy. It’s a strange, haunted world these characters live in, whose secrets only a master of the dark arts may access, so the hints of bigger, unexplained mystical forces operating on the periphery of the story help to put us in the appropriate mindset. I especially like the implications of the final segment, where John’s hillbilly magic gives a West African trickster spirit the tool he needs to overcome the evil voodoo priest who’s been holding him captive. (The implications of the celebratory scene that follows the battle, on the other hand, are more than a little unfortunate.) The shooting locations in Arkansas and western North Carolina lend the film a vital authenticity that compensates somewhat for the absurd notion of hippies springing up by spontaneous generation in a place where apparently nobody has ever heard of Janis Joplin, LSD, or the Vietnam War. Another source of authenticity is the way the use of magic is depicted most of the time, although there’s a bit of a tradeoff involved there. Apart from Ugly Bird, The Legend of Hillbilly John doesn’t usually go in for visible displays of supernatural power. We never see Polly Wiltse creating gold, and the transformations that overtake her and her home at the end of the segment happen between camera cuts. Nor are there any special effects involved when O. J. Onselm tries to paralyze John, or when Anansi and Captain Desplaines go at it. It’s disappointing from the standpoint of spectacle, but also realistic in the sense that people who believe in such things as charms, hexes, and the Evil Eye must do so without any rays of colored light or whatever to support their credulity. Of course, the real reason for the absence of visible magic is almost certainly a lack of money in the budget for it, but it works just the same. It also helps that the big exception to that rule— Ugly Bird— is pretty nifty, despite a few unmistakably cut corners in both the animation and the stop-motion puppet itself. So although I wanted considerably more from a John the Balladeer movie than The Legend of Hillbilly John delivers, I’m also pleased that I finally caught up with this one.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact