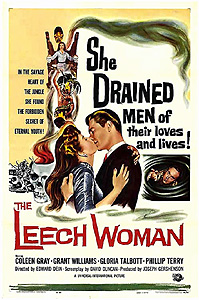

The Leech Woman (1959/1960) **Ĺ

The Leech Woman (1959/1960) **Ĺ

Normally when a major studio and a minor one release suspiciously similar movies at about the same time, we can be reasonably sure how it happened. Somebody at the little studio heard about a film under production at the big one, and decided to grab a piece of the action for themselves. The Asylum infamously built their whole business model around such cinematic claim-jumping, but they were hardly the only ones doing it. Roger Corman was a master of the ďscoop the majorsĒ game in his day, and like the Asylum folks, he took undisguised, justifiable pride in his ability get his cheap knockoffs into circulation before the pricier pictures he was copying. So when we observe the marked similarity between Cormanís late-1959/early-1960 Allied Artists quickie, The Wasp Woman, and Universal Internationalís The Leech Woman, also shot in Ď59 and released in Ď60, itís tempting to assume that this is yet one more case of an oft-observed phenomenon. Iím not so sure thatís really what weíre looking at, though. The Leech Woman was hardly a prestige production, after all. Indeed, some sense of the studioís esteem for it may be surmised from the fact that Universal sat on it until they needed a supporting feature for their import of Hammerís The Brides of Dracula. And if the temptation to steal a march on The Leech Woman was slight, the opportunity was at least equally so. Itís one thing for a small, nimble production to outmaneuver a lumbering juggernaut like Jurassic Park, but quite another to subject a fellow low-budget programmer to the same treatment. That said, if the resemblance between The Leech Woman and The Wasp Woman really is just a coincidence, itís one of the most remarkable Iíve seen lately.

Dr. Paul Talbot (Phillip Terry, from The Monster and the Girl and the 1947 version of Seven Keys to Baldpate) is an endocrinologist whose work focuses on slowing down the aging process. Like a lot of movie scientists, Talbot wears the deep-seated psychological motivation for his studies like a slogan on a t-shirt, right out where everyone can immediately see it: heís repulsed by the physical manifestations of age, especially in women. So good thing he married a dame considerably older than him, huh? That would be June Talbot (The Phantom Planetís Colleen Gray, who was thirteen years younger than Terry in real life, and looks it even despite about four pounds of old-age makeup). Itís difficult to imagine what brought the two of them together, since Paul is a completely unrepentant asshole, and June has old-people cooties. In any case, the honeymoon is well and truly over nowó the current state of the Talbotsí marriage is a veritable three-ring circus of mutual psychological abuse, with June unmistakably getting the worst of it. Realistically speaking, the only thing maintaining Paulís interest in his wife is the possibility that he may one day persuade her to volunteer as an experimental subject for his anti-decrepitude experiments, which June has thus far adamantly refused. Weirdly enough, though, June is still in love with Paul, so itís no wonder she feels compelled to spend most of her life sloppy drunk.

When we meet the Talbots, Paulís work is at an impasse, and moodiness is making him an even bigger bastard than usual. He and June have an especially vicious fight when she comes to visit him at the lab, escalating until Paul announces that heís had enough, and will be initiating divorce proceedings at the earliest opportunity. June rushes home to get blasted, and calls her friend (and Paulís lawyer), Neil Foster (Grant Williams, from The Incredible Shrinking Man and Doomsday Machine), to tell him all about her latest marital trauma. Paul, it would seem, is going to be needing a different attorney for this particular job.

Or on second thought, maybe he wonít be needing an attorney at all. That same afternoon, an old black woman named Malla (Estelle Hemsley) comes to the lab in response to one of Paulís ads for research volunteers of great longevity, and she unexpectedly puts his studies onto a whole new track. Malla claims to be over 150 years old, and the tests Paul and his assistant, Sally (Gloria Talbott, of I Married a Monster from Outer Space and The Cyclops), run on her corroborate her seemingly impossible story. The old lady has a curious background. She was born into an African tribe called the Nandos, but abducted by Arab slavers when she was little more than a child. Up until recently, Malla believed herself to be the last Nando alive, but it has come to her attention that a small remnant of her people still exists in a remote stretch of dense jungle. That matters for Talbotís purposes, because she attributes her incredible lifespan to the use of a drug from back home (I assume sheís not talking about peri-peri, ďNandoĒ notwithstanding), which slows aging to a crawl when taken regularly in small doses. She gives Paul a bit of the stuff for analysis, but whatís really interesting is that the Nandos are supposed to have knowledge of a second substance that, when combined with the age-retarding drug, can actually make people physically younger! Malla says sheís going home soon to seek out her lost kinsmen, and Paul gets it into his head to make his own expedition to Nando country. He also gets it into his head to call off the divorce now that thereís a clear prospect of not merely arresting Juneís aging, but indeed reversing it. Of course, he doesnít say anything to her about the real reason for his change of heart when he comes home and suggests that instead of splitting up, the two of them should try to reconnect via a working holiday in Africa.

What follows is pretty standard. Paul hires a guide (John Van Dreelen, from 13 Ghosts and The Clone Master), the guide assembles a team of native bearers upon arrival in Africa, and then itís nothing but pretending to interact with stock nature footage for the next reel or so. Paul and June renew their hostilities while trekking through the recycled jungle, and Bertram Garvay the guide starts taking an interest in her (although it would be going too far to say that he takes a liking to her). Hints emerge that Malla is not far ahead, leading Paul to begin pondering seriously how to approach her for a peaceful introduction to her tribe. But before he makes much headway in that direction, a Nando war band ambushes the Talbot party, massacring the bearers and taking the three whites captive.

Inevitably, itís Malla who saves the prisonersí asses. Despite not having set foot in this village at least since the 1820ís and possibly ever, the old lady seems to command a certain amount of authority. Enough, anyway, that nobody objects when she invites Garvay and the Talbots to witness her peopleís greatest secret, the ritual of renewal. Apparently itís something that only women get to do, on the grounds that old age sucks twice as hard if youíre female; a woman who is tired of living may imbibe the Nandosí restorative composite drug to enjoy a brief return to her glory days before committing ritual suicide. This, of course, is what Paul came here to see. The secret second ingredient turns out to be fluid extracted from the pineal gland of a living manó well, living up until the moment of extraction, anyway. If Paul has any ethical qualms about using such techniques in his own research, they evaporate when Malla takes her dose of the youth potion, and transforms into what looks like a woman of 30 at the most. (Specifically, she turns into The Wizard of Baghdadís Kim Hamilton.) The trouble is, June may have lousy taste in men, but ultimately sheís no fool. After Mallaís demonstration, she figures out at once what this African adventure and the reconciliation that preceded it are really about. June is no more interested in being a lab rat here than she was back home, and she devises on the spot a diabolical revenge when Malla offers to let her have the next turn at rejuvenation. Going next means first selecting a man to be her pineal-fluid donor, and while Malla intended her tribesmen to be the recruitment pool, June has something a little different in mind.

That still leaves Garvay and the refreshed June in the Nandosí clutches, and Malla has made no bones about her peopleís intention to kill the outsiders sooner or later. Naturally, neither June nor Bertram likes that plan, and theyíve got a hidden advantage over their captorsó they know where the explosives are. Garvay gets Mallaís okay to go searching through the luggage that the warriors confiscated earlier, on the pretext of finding some jewelry of Juneís to present as a gift for the Nando leaders. June did indeed bring some pretty impressive necklaces along (who the fuck knows why?), but the main thing the guide salvages is about half a dozen sticks of dynamite. You know what makes for a really effective diversion? Blowing up peopleís whole fucking village, thatís what! The Westerners make their getaway, and Garvay quickly finds their way to a river that will eventually lead them to a more populated area. Explaining that last part to June maybe isnít the smartest idea, though. The effects of the Nando youth potion are temporary, and when they wear off, June goes just a little bit nuts. Also, she smuggled some of the anti-aging powder out of the village during the escape, so all she would need to become young again is some more pineal fluid. Garvayís, for example.

June finds herself in a bit of a bind upon returning to the States, of course. Questions about Paul and Bertram can be deflected easily enough by saying that the party was attacked by savages in the jungle. Itís even technically true. But people donít normally come home from vacation decades younger than when they left, so June will have some explaining to do in the event that she meetsÖ well, anybody she knows, really. Thus it is that she acquires a niece nobody ever heard of before, who has come to stay with her in her hour of sorrow. And if folks see the niece a lot more often than they see June these days, the widow Talbot has every reason to want her privacy. As it happens, though, people see June quite a bit more frequently than sheíd like, because her body is developing a tolerance for the Nando drug. She hadnít intended to take up serial killing in her spare time, but what do you expect her to doó get old? Thatís crazy talk. Soon a detective (Charles Keane, from Curse of the Undead) is looking for her based on a calling card discovered on one of her victims, and thatís another hassle she has to manage. A more immediate and perhaps more dangerous hassle arises when Neil Foster meets June in her rejuvenated state. Sure, Foster is already dating Paulís former lab assistant, but once the new June comes round his office to close out Paulís affairs, itís infidelity at first sight. Sally quickly catches on, and she determines to fight for her man, even if he is a fickle, two-timing asshole who doesnít want her anymore. These are exactly the sort of complications that can get a murderer into trouble, you know?

Thereís a lot not to like about The Leech Woman. The distractingly obvious old-age makeup, the tiki-bar African village, the intensely racist portrayal of the Nandos and the Talbotsí native bearers, the dreary slog through the stock-footage jungle, and so on. What makes up for all that is how charmingly nasty and mean-spirited this movie is. Itís like the 70ís suffered premature ejaculation, and The Leech Woman grew from the wet spot. Everyone in the film is a loathsome, self-serving, and totally unsympathetic slimeball, willing to fuck over anybody for the slightest personal gain. Even characters who look at first like innocent victims turn out to fall somewhere on the spectrum between amoral schmuck and complete monster, as when Sally responds to Neilís final betrayal by going after June with a pistol in her purse. Such a cast of scoundrels is a rare thing to see in a film from a major studio, especially in this era, and that brings us, in a roundabout way, back to The Wasp Woman.

I grant you that on a plot-point-for-plot-point level, The Leech Woman and The Wasp Woman donít sound as though they have much in common. However, the same core premise drives them both: an aging woman rebelling against the passage of time with the aid of a mad-science drug becomes a murderous fiend. The fascinating thing about directly comparing the two movies is that Universalís interpretation turns out to be the scummy exploitation hack-job, while Cormanís is unexpectedly thoughtful and mature once you get past the cheesy monster suit. The Wasp Womanís titular were-bug has every legitimate reason to gamble her humanity on a chance to cheat old ageó as a fashion model turned cosmetics magnate, she makes her whole living from being young and beautiful, and her industry is one of the few in which women could attain the kind of wealth and power that male entrepreneurs of equivalent rank took for granted in the 1950ís. Furthermore, she is literally not herself whenever she kills people, and thereís never much sense that sheís getting her just punishment for trying to step out of her place, even though she herself is always the driving force behind the experiments that turn her into a were-wasp. The Leech Woman is much less forgiving of June Talbot, and gives us correspondingly less room to forgive her, either. Remember that regaining her youth was never her idea. Juneís initial experience with the Nando rejuvenation drug is purely an act of revenge against her abusive husband, assented to only when she recognizes the ďpoetic justiceĒ potential of making Paul sacrifice himself to the very experiment that he dragged her all the way to Tanganyika to perform. But once the deed is doneó once Paul is dead, and his stolen pineal fluid has undone the work of time on her bodyó June is suddenly willing to kill pretty much anybody to prevent herself from returning to normal. She commits her crimes in complete possession of her faculties, too, even going so far as to devise a pretty slick gigolo-hunting routine.

That last part is maybe the most genuinely interesting thing about The Leech Woman. Fluid-harvesting movies are so common as to constitute a weird little subgenre of their own, but from Dr. Mirakle killing hookers in the name of Science! in Murders in the Rue Morgue to Elizabeth Bathory bathing in blood for cosmetic purposes in Countess Dracula, the preferred victims are nearly always female, and very frequently virgins. Not so in The Leech Woman. Here itís only mature and virile men who can provide June with the pineal fluid she needs, as she discovers to her disadvantage in the end. My guess is that screenwriter David Duncanís main reason for doing it this way was to keep any hint of lesbianism out of the film (how times have changed, huh?), but it still gives The Leech Woman another point of refreshing difference from the norm.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact