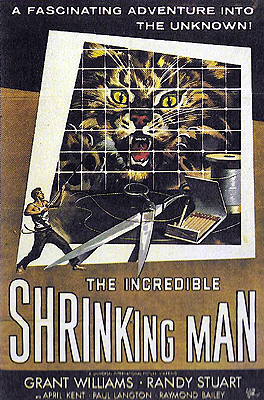

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) **˝

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957) **˝

One might persuasively argue that the 1950’s were the years when America’s ongoing love affair with bigness really hit its stride. Automobiles, women’s hairdos, and transcontinental bombers were just a few of the conspicuous things that became conspicuously more enormous during that decade, and if we extend consideration to all the myriad items which first appeared in the 50’s, and made their debut in plus-size form, then we’re probably talking about a simple majority of the stuff which the typical American would encounter over the course of an average day. And of course, in the world of the movies, the 50’s saw huge versions of practically everything animate arrive on the scene as well: giant lizards, giant snails, giant people, and of course giant bugs of species beyond all but the most dedicated counting, the vast majority of them owing their excessive size to some manner of brush with the mysterious power of ionizing radiation. Leave it to Richard Matheson, however, to do things a little bit differently. In his 1956 novel, The Shrinking Man, Matheson put the exact opposite spin on the popular theme of radiation-induced cell-growth fuck-ups, and used it as the jumping-off point for a thinking person’s pulp horror story nearly the equal of his earlier I Am Legend. The Shrinking Man, despite being published as a paperback original, did quite well, and proved to be one of its author’s most enduring works. It also caught the eye of Universal Studios, which snapped up the film rights and commissioned Matheson himself to write a screenplay; directorial duties would go to Jack Arnold, who was probably the studio’s most respected director of horror and sci-fi movies during this period. The results were rather mixed, with the finished movie alternating sharply between the brilliantly effective and the almost unbearably corny, and the main impression I get watching it is that Matheson should have had more trust in his writer’s instincts, while Universal should have trusted the production as a whole with a slightly bigger budget for a somewhat expanded running time.

The movie, unlike the novel, unfolds in a perfectly linear manner. It begins with Robert Scott Carey (Grant Williams, from The Monolith Monsters and Brain of Blood) and his wife, Louise (Randy Stuart), on a boating vacation together, somewhere off the Florida coast. While Louise goes down below to fetch a beer for her husband, the cabin cruiser drifts into a strange cloud of mist, which leaves Scott’s body covered with a dusting of even stranger silvery flecks. Neither one thinks much of the occurrence until six months later, when Scott notices that his clothes no longer fit. The waistband of his pants wants to slip down toward the swell of his buttocks, his shirt billows voluminously around his torso, and most alarmingly of all, the cuffs on both come much too far down around his extremities. Nor is it possible to pass the whole thing off as a mix-up at the cleaners, for every garment Scott owns is too big for him in exactly the same way. Scott goes to see his doctor (William Shallert, from Tobor the Great and Gog) for a physical, and discovers in doing so that he has lost both ten pounds and nearly three inches of height. The doctor disregards Carey’s concerns, attributing the lost weight to overwork and the lost height to errors in measurement on previous occasions, but Scott himself is not convinced. He’s right not to be. The shrinkage continues over the coming weeks until it becomes so obvious as to be undeniable— as when Scott notices that he and his wife are now of equal height. Carey’s regular doctor calls in a specialist on growth disorders, Dr. Silver (Raymond Bailey, of Tarantula and The Space Children), and it is Silver who discovers that Scott’s body has become impregnated with some sort of radioactive material. In particular, it would appear that whatever was in that cloud over the ocean combined at some point with a pesticide which Carey ingested from the spraying of the trees in his neighborhood to form some never-before-seen chemical compound which is now causing his body to shed matter at an unprecedented rate. Since nothing of the sort has ever been known to medical science, Silver frankly admits that he has no way of predicting what chance he may have of arresting, let alone reversing, the process, but he assures the Careys that he and his colleagues will do everything within their power to set Scott’s system aright again.

Carey, meanwhile, keeps right on shrinking, and his sense of helplessness, hopelessness, and indeed worthlessness grows in inverse proportion to his decreasing stature. To begin with, there’s the simple fact that the resolution to his problem is totally out of his hands, meaning that he really is helpless on that score. He’s also had to take a leave of absence from work, partly in order to make himself readily available to Silver and his team, but also because his condition is starting to give his coworkers the willies— the company he works for is on the periphery of the nuclear research industry, and rumors are circulating that Carey’s shrinkage was caused by something he was exposed to on the job. Fortunately, the owner of the company is Scott’s older brother, Charles (Paul Langton, of The Snow Creature and It!: The Terror from Beyond Space), who is more than willing to keep him on the payroll during his period of infirmity. Even a brother’s generosity has its limits, though, and when Charlie’s business hits a rough patch, causing his charity toward Scott to imperil the firm’s solvency, that limit is reached. Scott might have hated taking handouts from Charlie, but he hates being totally unable to provide for himself and Louise even more, and in the end, he grudgingly submits to the media circus his life was rapidly becoming anyway, and signs a book deal with some tabloid-minded publisher or other. And as Scott continues to grow smaller and more powerless, he increasingly takes out his frustrations on Louise, being a prick to his long-suffering wife on an ever grander scale.

Then something happens to reset Carey’s perspective. On the night when his height hits 36˝ inches, he has what amounts to a temper tantrum, and flees the house. There’s a carnival in town this evening, and shortly after Scott takes a seat in the most inaccessible corner of the local coffee shop, one of the sideshow midgets stops in for her break. Her name is Clarise Bruce (April Kent, who is decidedly not a midget), and when she sees Carey, she asks to join him. For the first time since his shrinking became really noticeable, Scott finds himself faced with a woman in whose company he can feel normal, and he spends a lot of time with Clarise after that night. (The film frustratingly ignores Louise’s reaction to this development completely.) It’s also right about then that Dr. Silver calls to inform Scott that he’s come up with a drug which he believes has a 50% chance of stabilizing Carey’s condition, though it will certainly not restore any of his lost size. Between the advent of Clarise and a whole week with no shrinkage, Scott’s spirits begin to lift, and he allows himself to find hope once more. The effect of Silver’s drug proves to be temporary, however, and the next change of scene presents us with the startling spectacle of Scott living in a dollhouse on the living room floor.

Even that minimal degree of normality is about to be stripped away, too, for it just so happens that the Careys have a pet cat. Now I yield to no one (or at least to no male) in my ailurophilia, but you know what? I wouldn’t take my eyes off my cat for a second if I ever caught a disease that caused me to shrink to a height of five inches. You might just as well play Russian roulette with an automatic pistol. Louise accidentally lets Butch into the house one evening while she’s on her way to the corner store, and the cat wastes no time in noticing the tiny, unarmed creature in the dollhouse. Carey escapes only by falling into the basement, and when Louise comes home to find Butch sniffing at a shred of Scott’s clothing, she jumps to the obvious conclusion. Scott, for his part, is far too small now to scale the basement steps unaided, so there’s nothing else for it but to accept that the cellar is his world from now on. Food, water, and shelter are his most immediate problems, but he quickly discovers that there’s a danger looming on the horizon which is arguably even greater than a hungry cat. There’s a spider in the cellar, and it’s going to be bigger than Carey in the not-too-distant future.

The Incredible Shrinking Man is one of those films which you’re likely to enjoy a hell of a lot more if you’ve never read the book. While it’s awfully good for a cheap-ass late-50’s programmer, the story loses virtually everything that made the novel work so well in the translation from print to celluloid. Matheson himself reports that the reasoning behind his decision to begin The Shrinking Man with Carey already in the basement, and fill in the rest of the story with flashbacks, stemmed from his perception that the linearly-structured early drafts of the novel took too long to get to “the good stuff.” And wouldn’t you know it, that is precisely the most obvious failing of The Incredible Shrinking Man, in which Matheson inexplicably backtracked to the narrative strategy he had already realized wasn’t right for the story. That structural awkwardness is not the movie’s most serious failing, however. The most serious failing is the short shrift the film gives to the psychological— and especially psychosexual— havoc which the experience of shrinking wreaks on its hero. Between the short total running time and the perceived need to get Scott down to the basement in a timely manner, there’s simply no room to develop the personal aspect of the story, and because Matheson is an author whose best work is all about the personal aspect, The Incredible Shrinking Man winds up feeling hurried and incomplete. It was also not a smart idea to make such frequent use of voiceover to establish what’s going on inside Scott’s head after the fall into the cellar. Better to have him talk to himself in an effort to simulate human contact, and let the inner landscape come into view that way.

Nevertheless, there is much to enjoy about The Incredible Shrinking Man. Most obviously, the special effects in this film are extraordinary. The back-projection is the probably the best I’ve seen since the opening of The Bat Whispers, and it mostly maintains that high standard throughout. The numerous matte shots are equally well-handled, comparing favorably to others of their kind even from movies made 20 years later. But most impressive of all is the forced-perspective trickery, which I’m not sure I’ve ever seen equaled. Though the technique is conceptually simple, it can be surprisingly difficult to get right. Here, the forced-perspective scenes are consistently the most convincing in the movie, creating a perfectly believable illusion of a four-foot-tall Grant Williams interacting with a full-sized Randy Stuart. The scenes with the spider— usually portrayed by a live tarantula— meanwhile, put Jack Arnold’s previous foray into the field of altering the apparent size of arachnids to shame. (The use of a completely different effects team is surely the main reason why.) The spider scenes also, and more importantly, are exceptionally suspenseful by the standards of 1950’s monster movies, and in general, Carey’s struggle for survival once he shrinks to doll-size contains the finest work Arnold had turned in since Creature from the Black Lagoon (at least as long as Grant Williams keeps his goddamned voiceover shut). Its reputation may be inflated a fair sight beyond what it deserves, but The Incredible Shrinking Man is on most counts a respectable effort.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact