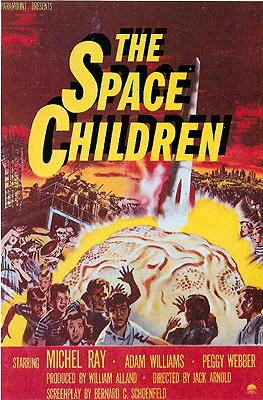

The Space Children (1958) ***

The Space Children (1958) ***

H.G. Wells was inspired to write The War of the Worlds at least partly by the extermination of the Tasmanian Aborigines. What would it be like, he wondered, for Britain to experience the same kind of calamity that it had inflicted there, and to a lesser extent on peoples all over Africa, Asia, and Oceania? How would Europeís arch-colonialists respond to being invaded and overrun by a culture whose technological and economic advancement outstripped theirs as starkly as British technology and productivity outstripped that of the Maasai, the Malay, or the Maori? Wellsís thought experiment would be rerun (usually with a great deal less care or conscious introspection) any number of times during the sci-fi movie boom of the 1950ís, including, as was only fitting, in a direct adaptation of his novel. Itís difficult to spot the basal colonial allegory in those films, however, because itís generally supplanted and overshadowed by Cold War anxieties about the looming threat of a Third World War even more terrible than the last two.

Thereís a second strain of 1950ís sci-fi, though, in which the colonial metaphor is closer to the surface, and which comes at it from a very different perspective. In these movies, the aliens are not rapacious conquerors, but benevolent civilizers, intervening in human affairs to prevent a promising but primitive species from annihilating itself with newly acquired power that it lacks the wisdom to wield responsibly. This breed of space invader does for humanity what apologists for colonialism like Rudyard Kipling claimed Europeans were doing for their nonwhite subject-peoples overseas, and the more or less explicit message is that our species should be grateful for the attention. Call it the Little Green Manís Burden, if you will. The ur-text here is obviously The Day the Earth Stood Still, but there are enough others to constitute a subgenre within a subgenre. The Space Children is a really extraordinary example, because it hides its Little Green Manís Burden content inside a form that typically has exactly the opposite philosophical valence. On the surface, The Space Children looks like another paranoid parable of communist infiltration, and only gradually does it become apparent that director Jack Arnold and screenwriters Tom Filer and Bernard C. Schoenfeld intend the mind-bending extraterrestrials to have the right of it.

Aerospace technician David Brewster (Without Warningís Adam Williams) has just been transferred. His firm is one of the main contractors on the Thunderer project, and his bosses are sending him and his entire family to take up residence in a hastily assembled beachfront trailer park in Echo Point, on the grounds of the site for the final phase. Thunderer is a highly classified military program, and thus far none of the nuts-and-bolts designers have been permitted to see enough of anyone elseís work to understand what the finished product is even supposed to do. Maybe all the secrecy goes some way toward explaining why Davidís fretful wife, Anne (Peggy Webber, of The Screaming Skull), finds the move from San Francisco to Echo Point not merely a nuisance, but downright frightening. The Brewstersí sonsó twelve-year-old Bud (Michel Ray) and ten-year-old Ken (Johnny Crawford, from Village of the Giants)ó have no such worries, however. Indeed, they regard the situation as something of an adventure, even before the first time they see the weird thing in the sky over the shoreline. It looks a bit like a rainbow, except that it seems to come straight down from the heavens instead of arcing across them. Also, it makes a noise, although it seems as if neither of the boysí parents can hear it.

There are several other families ensconced in the trailers at Echo Point, but the only ones with whom weíll spend much time are the Johnsons next door and the Gambles on the other side of the court. Frieda Johnson (Vera Marshe, from The Phantom of 42nd Street and Tormented) is the first of the Thunderer wives to try her hand at befriending Anne, and she has hopes of her daughter, Eadie (Sandy Descher, the catatonic little girl in Them!), doing the same with Bud and Ken. Her husband, Hank (Jackie Coogan, from Mesa of Lost Women and Human Experiments), is a blustery, loudmouthed fellow, but not so much as to place him outside the fat part of the bell curve for 1950ís dads. Peg Gamble (Voodoo Islandís Jean Engstrom) is one of Thundererís computer programmers. (Remember that the hands-on business of programming was considered womenís work in those days. Fussing with all those punchcards was too much like typing and file-keeping to be worth a manís time.) Thatís a major problem for Joe (Russell Johnson, of The Horror at 37,000 Feet and This Island Earth), the unemployable drunk whom she was fool enough to marry after her first husband didnít come back from the war. It wounds Joeís manly pride something awful for his wife to be the breadwinner, and he unhelpfully compensates by tyrannizing his thirteen-ish stepson, Tim (Johnny Washbrook).

The Brewsters havenít even finished unpacking before David is summoned to the lab. Evidently Colonel Manley (Richard Shannon, from Conquest of Space), the Air Force officer in charge of the project, has decided that the time has come to reveal to the rank and file just what theyíre going to be doing at Echo Point for the next few months. Together with lead physicist Dr. Wahrman (Raymond Bailey, of The Incredible Shrinking Man and Black Friday), Manley explains that Thunderer is a six-stage rocket of unprecedented size and lifting power, intended to insert a satellite of commensurately immense girth into a controllable stable orbit. The satellite in turn is the launch platform for a new type of compact hydrogen bomb. With an arsenal of such weapons circling 1000 miles above the ground, the United States will have a nuclear deterrent even more formidable than the intercontinental or submarine-launched ballistic missileó one absolutely impervious to attack by any means yet devised or even imagined. Thereís a certain urgency to the work, though, because military intelligence has reason to believe that several other countries are cooking up something similar, and not all of them are friendly.

Itís while their father is up at the base learning that heís in the Armageddon business that Bud and Ken find the cave on the beach. Mind you, they arenít the first to do soó indeed, all the Echo Point children like to hang out there, treating it as a sort of secret clubhouse. And by an interesting coincidence (or is it?), whenever that funny not-exactly-a-rainbow reappears, it seems to point straight at the place. One morning, while the kids are all playing on the beach in a gaggle, Bud thinks he spots an object of some kind descending toward the cave via the beam from the sky. When they go to investigate, they find something on the ground inside that looks very much like a disembodied human brain, except that the crenellations of the cerebral cortex are all wrong, and thereís no clear division between hemispheres. Also, the thing both pulsates and glows, neither of which can be considered normal for the brain of any creature on Earth. Strangest of all, the brain-thing speaks after a fashion, transmitting its thoughts directly to the minds of the children. We donít get to hear what it says, however. Itís plain enough, though, that Bud and Ken have been entrusted to protect the cerebral alien from harmó although one canít help thinking thatís as much a courtesy to the neighboring humans as a precaution for the brainís own safety, for it can paralyze, erase memories, and even kill when it needs to, all through the power of its thoughts alone. In any case, from the moment the kids meet the brain-thing, they start taking an untoward interest in their parentsí jobsite, sneaking past the perimeter guards with uncanny ease and facing no apparent difficulty from even the stoutest locks. Soon thereafter, a rash of accidents too strange for mere sabotage to account for them begins plaguing the Thunderer lab, and although Dr. Wahrman is quick to notice the proximity of the children as a common denominator, heís at a loss to understand what that might mean.

The Space Children ends on a biblical epigram, from the Gospel According to Matthew: ďVerily I say unto youÖ except ye become as little children, ye shall not enter into the kingdom of heaven.Ē In doing so, it tips its hand, I think, about the unspoken driving force behind all Little Green Manís Burden filmsó a yearning for some godlike intelligence to come down and solve the problems that humans canít seem to stop making worse no matter what they do. If God Himself no longer considers that to be his department, then why not redirect the feeling into fantasies of an older civilization of wiser beings from a planet that actually has its shit together? For all the sinister implications that emerge when these movies are examined in a Wellsian frame of reference, they nevertheless display an implicit humility about our species that contrasts strongly against the triumphalism of contemporary space operas, lost world pictures, and the more conventional strain of alien invasion films. Indeed, in The Space Children, the coworker of Davidís who comes closest to embodying that triumphalism is among those who fall victim to the space brainís psionic power. Even so, itís worth observing that movies of this type rarely if ever show the aliens fixing anything directly. Instead, the saviors from outer space guide human action, whether by enabling and supporting the work of those clear-eyed enough to see the problems for themselves, or by threatening to hasten the extinction that we insist upon courting unless we shape up. The Space Children might be the first such movie Iíve seen, though, to acknowledge so openly that it always falls to the next generation to correct each successive age cohortís fuck-ups.

It would be interesting to be able to watch this film through the eyes of 1958. After all, in 2024, we know what happened a decade later, when a critical mass of young people belonging to the Echo Point kidsí generation really did attempt to set their elders straight. And on a more hopeful note, we also know (or at least, those of us who are nerdy in just the right way do) that concern over weapons very much like Thunderer figured prominently in the arms-control negotiations between NATO and Warsaw Pact nations during the Dťtente era. (Alarm at the prospect of renewed progress toward real-life Thunderers helped animate the scientific communityís opposition to Ronald Reaganís Strategic Defense Initiative, too, but thatís a somewhat bleaker tale.) What did The Space Children look like when the things it wasnít even trying to predict, really, were still safely in the realm of fantasy, and not some of the hottest hot-button issues of the subsequent two and a half decades?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact