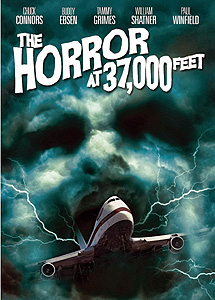

The Horror at 37,000 Feet (1973) -**½

The Horror at 37,000 Feet (1973) -**½

It’s been frequently observed that the made-for-TV movies that colonized such a broad swath of the airwaves during the 1970’s were remarkably consistent with regard to quality. Whereas their modern counterparts are apt to be utter stinkers, elevated just slightly above the level of direct-to-video movies, and the pioneering handful of films made for television syndication in the 1960’s collectively set an entirely new standard for awfulness, the movies of the week produced by the three major networks in the 70’s could be counted upon to achieve at least a professional grade of sturdy mediocrity, and not a few of them were really quite good. Furthermore, because the good ones have been disproportionately selected for preservation by the home video market, 70’s TV movies as a whole look even better today than they did at the time. You might have noticed, for example, that what little delving into this territory I’ve done so far has been devoted primarily to films that are now regarded as minor classics: Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Trilogy of Terror, Salem’s Lot. Yeah, well we can’t allow that state of affairs to go on any longer, can we? No, it’s time I dug up something from the other end of the spectrum, something to show that a 70’s telefilm could be every bit as dumb as contemporary drive-in fare, even if the natural conservatism of the networks would invariably hold it to a higher standard of workmanship. Something, that is to say, like The Horror at 37,000 Feet.

In Hollywood parlance, a “high concept” property is one where the premise itself is the main selling point, and would remain so even with a big star, a prestigious director, or any other obvious marketing angle attached to it. In practice, it tends to mean dizzying combinations of derivativeness and novelty, and on occasion a high concept movie has a concept you’d have to be high to dream up. The Horror at 37,000 Feet is awfully impressive in that regard. It is, for all practical purposes, Airport meets The Exorcist, as a transatlantic overnight flight full of jerks we don’t care about is brought to the brink of disaster by a demonic entity in the cargo hold, and only a faithless ex-priest has the slightest chance of salvaging the situation! And for the “Twilight Zone” fans among us, the folks at CBS have considerately cast William Shatner as that reluctant hero, facing something theoretically much grimmer than a gremlin on the wing— and a further 17,000 feet off the ground than last time, to boot!

The doomed flight here is an AOA (whatever that stands for) 747 taking off from Heathrow Airport under the command of Captain Ernie Slade (Chuck Connors, of Captain Nemo and the Underwater City and Maniac Killer). Curiously, there are only ten passengers booked for the flight, but as copilot Frank Driscoll (H. M. Wynant, from Conquest of the Planet of the Apes and Hangar 18) explains, most of the plane’s lifting capacity is taken up by the 11,000 pounds of “architectural features” in the cargo hold. Evidently one of those ten passengers— architect Alan O’Neill (Roy Thinnes, from The Norliss Tapes and Satan’s School for Girls)— has disassembled the central chapel from a medieval abbey on land belonging to his wife, Sheila (Jane Merrow, of The Woman Who Wouldn’t Die and Island of the Burning Doomed). We’ll later learn that the land in question has been sold off to a developing concern, the abbey slated for demolition, and that O’Neill arranged to salvage the chapel for installation in the couple’s home Stateside as a gesture of generosity toward his wife and her family. Not that Sheila seems the slightest bit appreciative, mind you. Indeed, I’m forced to conclude either that she’s actively pissed off about the preservation of this small piece of the family heritage, or that she’s just a horrible person who enjoys starting fights with people who love her for absolutely no reason.

Admittedly, the removal of the old chapel has not been without its attendant headaches, so maybe that’s what’s crawled up Sheila’s ass. A bunch of concerned locals got together to launch a baseless lawsuit against the O’Neills to make them leave the chapel where it was (presumably they’d have taken on the developers next if the judge hadn’t smacked them down), and now their leader, Mrs. Pinder (Tammy Grimes), is on her way across the ocean to bring even more baseless suit in an American court. And yes, that does indeed mean that Mrs. Pinder is on the same flight as Alan and Sheila, doing her best to annoy them from her seat back in coach. As for the other seven passengers, most of them could easily have been lifted straight from whatever Irwin Allen movie was in theaters on February 13th, 1973, when The Horror at 37,000 Feet was first broadcast. There’s Glenn Farlee the arrogant plutocrat (Buddy Ebsen), Annalik the fashion model (France Nuyen, of Death Moon and Battle for the Planet of the Apes), Dr. Enkala the philosophically inclined physician (Paul Winfield, from Gordon’s War and The Terminator), Steve Holcomb the B-list cowboy actor (Roar’s Will Hutchins), Jodi the unaccompanied child (Mia Bendixsen, who also had small parts in Prophecy and Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains), and Manya (Lynn Loring, from Black Noon and Journey to the Far Side of the Sun), the woman of so little intrinsic importance that I had completely forgotten her name by the time the credits rolled. Manya is worth noting only because her hard-drinking companion (Brother? Friend? Lover? Who knows?) is Paul Kovalik (Shatner), a simultaneously secretive and bellicose man whose alcohol-induced antics are clearly leading up to some major second-act plot development.

Weird stuff starts to happen almost immediately. Just barely is the plane off the ground before Sheila finds herself unable to raise anything on her headphones but ominous voices chanting in Latin and calling her name. Sheila is somewhat less freaked out by this than you might imagine, however, because apparently the experience is approximately in line with a nervous breakdown she had some time ago. Also in the “strange, but easily disregarded so long as it causes no actual problems” column are the mysterious, intense chill radiating from the cargo hold and the newly developed tendency of the elevator communicating between the Boeing’s three decks to become jammed whenever the younger and more skittish of the two stewardesses (Brenda Benet) is inside. What is completely impossible to ignore is the unexplained current of air resistance that the plane encounters once it’s climbed to cruising altitude. What starts as a bit of extra drag that the onboard instruments can’t account for turns into something truly beyond the bounds of known physical law by the time Slade and his crew reach a point 25 nautical miles west of Heathrow. (No, I don’t think screenwriters Ronald Austin and James D. Buchanan understand how quickly a jet airliner would cover that short a distance, either.) They find themselves literally standing still in the air, despite running the engines at a power output that ought to suffice for 640 knots! The only way to account for such a thing would be if the 747 were fighting a 640-knot headwind, and since AOA doesn’t offer service to destinations on Jupiter, there’s no way in hell any such thing could be happening. What’s more, that impossible wind shifts direction to remain pointed squarely at the plane’s nose no matter which way Slade turns after obtaining permission from ground control to return to Heathrow. Most of the passengers, being inexperienced flyers, don’t notice anything amiss, but Farlee has made this trip dozens of times, and he knows what the view from his window is supposed to look like. Slade and the other crewmembers manage to shut him up before he has a chance to sow any panic, but there’s clearly a time limit on the obfuscatory tactics the captain adopts to do so.

No amount of obfuscation will suffice, though, when the chill in the cargo hold turns into a frigid wind blasting forth from the crates containing O’Neill’s dismantled chapel, killing flight engineer Jim Hawley (Russell Johnson, from Hitch Hike to Hell and The Ghost of Flight 401)— and Mrs. Pinder’s pet dog along with him. Slade’s investigation of the craziness below decks goes pretty far wrong, too, as some unseen thing strikes him, leaving marks that Dr. Enkalla identifies as frost burns, but which are unmistakably in the shape of a set of fingers. Meanwhile, Sheila goes into a seizure, and starts intoning the same Latin chant that she had been hearing on her headphones earlier. Mrs. Pinder finally steps up to deliver her payload of exposition at this point, revealing herself as a representative of the modern-day Druid coven that worships in secret at the condemned abbey, and explaining that the chapel she and her fellows were fighting so hard to protect is consecrated to some Celtic winter deity. This god requires a sacrifice from Sheila’s family line once each century on the night of the summer solstice. That’s tonight, and if Mrs. Pinder is to be believed, nobody is getting off that airplane until Sheila surrenders herself to the supernatural presence in the hold. Then again, Manya also comes forward now to out Paul as a recently defrocked priest, and while Kovalik himself evinces no interest in throwing down with one of the Old Gods, I think we all know he’s going to wind up playing Lancaster Merrin (or perhaps Damien Karas) to the Winter Spirit’s Pazuzu before all is said and done.

The Horror at 37,000 Feet’s most striking feature is the contrast between the clunky professionalism of the production and the desperate weirdness of the subject matter. Network television was the default mass entertainment medium of the American people during the early 1970’s, and that exalted status brought a certain mindset with it. “Standards and practices” wasn’t merely a euphemism for censorship, although that certainly was one of the meanings implied by the phrase; fundamentally it was about quality control, albeit with a built-in upper-middle-class value assumption that giving offense was necessarily a sign of poor quality. The chronically undercapitalized independent stations that broadcast on the UHF band would continue to take whatever they could get until well into the 1980’s, but the networks always saw to it that even when their programming wasn’t good (which, then as now, was most of the time), it would for damn sure be presentable. Most of the people involved in The Horror at 37,000 Feet’s creation had resumés a mile long, and all that experience shows throughout. Cinematography, blocking, lighting, line delivery, sets, props, costumes, sound design— none of it ever rises above the level of workmanlike, but none of it ever falls below that standard, either. (Well, okay. William Shatner’s toupee is one of the worst I’ve seen anywhere, bearing no resemblance whatsoever to the portion of his hair that’s still permanently attached to his head.) But then you look at the script that all this unpretentious competence has been mustered to realize, and the cognitive dissonance is just mind-blowing. This is the sort of cynical mix-and-match cash-in premise that you’d expect from one of the more disreputable European film companies of the day, and the writing overall is practically in Eurocine’s territory. Attentive viewers will be left wondering why Druids would conduct their rites in Latin, how Mrs. Pinder’s cult managed to maintain the continuity of their worship when there’s been a Christian abbey sitting on top of their sacred site for the last 500 years, and why a deity associated with the icy winds of winter would set the holiest observance of its liturgical calendar on the night of the summer solstice. They’ll puzzle over the huge personal risk at which Kovalik puts himself during the climax— exactly when the much safer strategy he had counseled earlier was finally starting to work— and conclude that it must be because the only cribs from The Exorcist that we’ve seen during the past hour and ten minutes have been inexcusably subtle and oblique. They’ll ask why the writers bothered to set up Annalik as a romantic rival for Sheila if there was no intention to do anything with the subplot, and sigh resignedly over the revelation that the model, as a Southeast Asian, is naturally well versed in voodoo— which is functionally interchangeable with Mrs. Pinder’s Celtic paganism! I hasten to emphasize that The Horror at 37,000 Feet does not itself fulfill this promise, but it’s enough to raise the possibility of a stealth anti-classic, a film as bottomlessly ridiculous as anything dreamed up by Ted V. Mikels or Jesus Franco, but with enough surface polish that you don’t recognize what you’re seeing until after the fact.

This review is my extremely belated contribution to the B-Masters Cabal roundtable on made-for-TV movies from the golden— no, let’s make that pyrite— age of such things, the late 60’s through the early 80’s. Click the banner below to see what my collegues who were actually on time had to say on the subject.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact