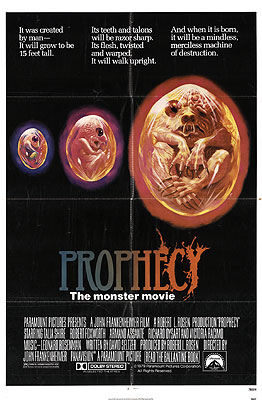

Prophecy (1979) ***

Prophecy (1979) ***

Now, before you go getting your hopes up too high, thinking, “At last! El Santo has finally developed some taste!,” allow me to draw your attention to this movie’s release date. This is not-- I repeat, not-- the Christopher Walken movie about a civil war between factions of angels. I may get around to that movie someday, but not today. No, this Prophecy is John Frankenheimer’s almost ludicrously sincere environmentalist epic, in which an acrimonious conflict between a paper mill and an Indian tribe is complicated by the activities of a gigantic mutant bear.

Like all excessively earnest movies that would like to be seen as serious statements about serious social issues, Prophecy features a cast of characters whose one- or at best two-dimensional personalities any reasonably intelligent viewer will be able to fully assess within (at most) fifteen seconds of screen-time. It takes far less than that to pin down Dr. Robert Verne (Robert Foxworth, from Invisible Strangler and Damien: The Omen II), the film’s obligatory angry and disillusioned bleeding-heart liberal hero; all we need do is listen to the first line of dialogue spoken by the impoverished black mother of the rat-bitten infant that Verne spends his first scene examining in the mother’s blighted ghetto home. “Landlord said it was chicken pock...” the woman says bitterly. The rest of this scene will fully confirm our expectations of Verne’s character. He tells the mother he’s sending her baby to the hospital (doesn’t even ask about insurance), promises (tight-lipped with fury) to write up a condemnatory report on the landlord (absentee, of course) and to recommend that his agency file suit against him, has the mandatory “Man, I just don’t feel like I’m making a difference here” conversation with his boss-- the whole deal. The scene naturally ends with the boss offering Verne a chance to make a difference on a much larger scale than he can by treating rat-bitten babies. He wants Verne to go to Maine to weigh in on that dispute I mentioned earlier. He takes a bit of convincing, but we knew all along he’d go for it, didn’t we?

Verne’s wife, Maggie (Talia Shire-- Adrian from the Rocky movies, if you can believe that), is the closest thing to a fully developed, well-rounded character that we’ve got here. She basically shares her husband’s views, but she lacks his crusader’s fire, and while she respects Robert for it, she also doesn’t fully understand him. There is one particularly thorny issue between the Vernes-- that of childbirth and parenthood. Robert has clearly read The Population Bomb-- he refuses even to consider having kids. Maggie on the other hand wants nothing more. As the movie opens, it seems that this conflict is about to take on new urgency. Maggie is pregnant. This unconventional element of the plot will become the key to the best scenes in this movie-- the ones that elevate it in spite of itself to heights that Frankenheimer only wishes its rather clunky main body could attain-- so do your best to fight off the urges you will inevitably feel to tune out and dismiss the movie as so much drooling-monster bullshit. (Not that I have anything against drooling-monster bullshit... ask me about Forbidden World/Mutant sometime.)

When the Vernes arrive in Maine (well, the movie says it’s Maine-- it looks a lot more like Washington state’s Cascade Mountains to me), Frankenheimer again does exactly what we expect. First, he introduces Isely (Richard A. Dysart, the man who played Dr. Copper in John Carpenter’s unjustly maligned remake of The Thing), the director of the paper mill, who meets the Vernes to drive them to their cabins, mouthing the usual contemptuous, bigoted platitudes about the local Indians and singing the praises of his company’s environmental record the whole way up the mountain. They of course find the way blocked by a group of Indians, led by John Hawks (Armand Assante, who’s been in a whole lot of crap-- Judge Dredd, for instance) and his sister Ramona. Frankenheimer belabors the standoff on the trail for far longer than can be excused, but at least he follows it up with something unexpected-- a surprisingly vicious broadaxe-vs.-chainsaw fencing match between John Hawks and one of Isley’s men, a duel which ends in defeat for the less-heavily-armed Indian. Hawks’s comrades back off, and Isley continues the drive to the cabin. “These are violent people-- they get drunk, they get violent-- and you’ve got to show ‘em you mean business,” he says.

What makes this contest between the Indians and the mill so excessively ugly is that it’s about more than just the usual “the forest is our way of life” business (although Hawks will later say that in almost exactly those words). You see, something is making Hawks’s people sick-- bizarre motor-function disorders are rampant, stillbirths and hideous birth defects abound, and Hawks’s grandfather, M’Rai, the oldest man in the tribe (Nightwing’s George Clutesi), keeps burning himself with his cigarettes without noticing, as though something were wrong with the pain receptors in his skin. Because it is the late 1970’s, the tribe’s leadership is naturally inclined to look to the paper mill in its search for the source of the problem, making the entirely understandable assumption that it must take some incredibly nasty chemicals to turn a tree into a ream of stationery. Isely, for his part, is equally suspicious of the Indians, partly out of prejudice, but mostly because experienced woodsmen have started vanishing without a trace in the forest, and it seems to Isely that people who have declared their willingness to die for their cause might just be willing to kill for it, too. The situation reaches critical mass when a family of three on a camping trip in the woods is torn into tiny pieces one night on land that the tribe claims as its own. We in the audience saw it happen, so we know that it was no Indian that slew the campers (unless those birth defects that Hawks was talking about are much worse than he let on), but Isely jumps to the conclusion he’s long wanted to reach, and calls in the police to arrest Hawks.

Meanwhile, Dr. Verne has been snooping around, and he has seen some disturbing shit. In addition to the problems Hawks described, he has seen evidence of contamination on a broader scale. The trees around one of the ponds that the paper mill uses to store felled trunks when it gets backed up all have seriously deformed root-systems. Then there was the time he and Maggie were attacked by a mad-- but not rabid-- raccoon. Still more ominous, one day while he was out on the lake fishing, he saw a salmon big enough to swallow a duck whole (a salmon which did just that), and later, M’Rai shows him a tadpole nearly two feet long. His tour of Isely’s mill turns up nothing at first-- none of the bleaching or pulping chemicals ever leaves the plant, and Isely has the water purity tests to prove it-- but then Verne notices that Maggie got something on the soles of her shoes when she waded out to the boat that they had used to reach the mill. Maggie’s boots emerged from the water covered with a very strange silvery substance, a liquid that paradoxically felt dry to the touch-- mercury! Now, mercury is some extremely poisonous shit, and while I don’t know that I buy all of the things the characters in this movie say about it, I can tell you that it really does cause a degenerative nerve disease that impairs motor functions and kills the neurons that process pain. It can cause chromosomal damage and lead to some pretty ghastly birth defects, too. It also used to be used in the production of paper, before word got out how terribly destructive it could be, and it’s many times denser than water, in which it is not readily soluble, meaning that it could sink to the bottom of a pond or stream, where it wouldn’t show up on the kind of water-quality test that Isley uses. Ladies and gentlemen, I think we’ve found our culprit!

And not too much later, Maggie finds something at the site of the campers’ murder that should be able to convince just about anybody on Earth that the local ecology is 31 flavors of fucked. While her husband and Ramona are looking for evidence that might exonerate Hawks, and while the pilot of the helicopter that they rode out to the area becomes increasingly worried about their prospects for takeoff in the rapidly worsening weather, Maggie hears a truly hideous sound coming from a salmon net that some poachers had strung across a nearby stream. When she gets close enough to see, it turns out that the creature making the noise is, if anything, even more hideous than its vocalizations-- picture the monster from I Was a Teenage Frankenstein reinterpreted as a dog, picture a bear cub with no skin and only half a face, picture the aftermath of that scene in the 1986 version of The Fly where the baboon emerges from the telepod as a monkey-shaped hamburger; any of those will get you somewhere close to what this thing looks like. There are actually two of the creatures, but one is already dead (From exposure? From problems relating to its own grievously fucked-up anatomy?), and Verne seizes upon the idea that the other monster must be kept alive long enough to show to Isely and the local authorities. The only trouble is that the weather is now too severe for the chopper to take off, the Vernes’ cabin is much too far away to be reached before the mystery beast freezes to death, and the town is further still. The only viable option seems to be to make for the Indian village.

Now, let’s talk about this village for just a moment. Do you remember where in the country this movie is supposed to be set? That’s right, Maine. And do you remember from second grade American history what kind of houses the Indians in Maine built? No? Well I’ll tell you this, they sure as fuck didn’t live in goddamned teepees!!!! But guess what sort of structures this village is composed of. That’s right, goddamned teepees!

Anyway, Verne sends some of the Indians to town to get Isely and the Sheriff, while he sets up a sort of makeshift ICU in one of the goddamned teepees. (I’m sorry, I swear I’ll stop doing that-- it’s just that it really makes me mad.) The authorities arrive in time to see the baby monster with their own eyes, and there’s one of those big change-of-heart scenes that these social message movies are so fond of (although at least this time, the stimulus behind that change of heart is intense enough to make the scene somewhat credible). Unfortunately for all concerned, Isely’s arrival is followed in short order by that of the creature’s mother. Man, if you thought the kids were ugly... So Mom starts tearing up the village Gorgo-style, pulling off faces, biting off heads, throwing people into trees like she’s working on her fastball, and the only way anybody survives is by hiding out in the tunnels under the village, which serve as sort of a collective larder for the whole tribe.

The next day, the survivors are faced with the task of getting back to civilization without being eaten, hoping to Hell that the monster is nocturnal. Isely’s plan is to go up the mountain to the big radio tower to call for help while the rest of the group stays put in the relative safety of the village. (Riding the helicopter home is not an option, seeing as how the pilot was one of those who got their heads bitten off.) Now, you know what has to happen. Isely may have come around, but he’s still got a lifetime of Evil Capitalist karma to work off, so yeah, he’s not quite going to get to that radio. This puts the other survivors right back where they started, and it probably comes as no surprise to you that a big showdown with the monster is in the offing. I’ve seen worse monster showdowns in my time, but would somebody please tell me why, when it comes down to Verne vs. the mutant, this creature that has repeatedly demonstrated its ability to swipe your head right the fuck off your shoulders-- to the extent that nobody yet that has been so much as touched by it has lived-- would content itself with lifting the doctor off of the ground and bear-hugging (mutant-hugging?) him while he stabs it over and over again in the face with an arrow? Can anybody answer me that? Please?

But let’s end this review on a positive note, shall we? Earlier, I said that Maggie’s pregnancy was a major element of Prophecy’s story, and that it was the key to the movie’s best scenes. Remember, the problem here is mercury in the water, and mercury, at least according to the ecology of Prophecy, is one of those toxins that works its way into the food chain, and thus is able to fuck up everybody, in much the same way that DDT does-- it gets into the water, sinks to the bottom, and leeches into the soil; plants absorb it into their roots, they get sick; animals eat the sick plants, they get sick; sick animals have litters, the cubs are born defective. And remember also that I earlier mentioned a fishing trip on Verne’s part, on which he saw that monster salmon. Well, that fishing trip was a success, and that night Robert and Maggie had salmon for dinner. Pregnant Maggie had mercury-contaminated salmon for dinner. There is a fantastic scene maybe twenty minutes later in which Robert (who is, as yet, unaware that she’s pregnant) describes to Maggie in horrifying detail the mutagenic potential of mercury, completely misreading her escalating unease as sympathy for Hawks’s people-- as usual, seeing everything in his life through his liberal crusader’s eyes, unable to imagine that his wife’s trepidation might have a source closer to home. And why not? Verne is a white doctor. This is a man who experiences hardship only vicariously; how could it possibly occur to him that that pattern is about to change, drastically and catastrophically? The fact that it’s Maggie who finds the mutant cub, and who usually ends up being the one to carry it around only illustrates the situation more graphically. If the baby comes to term, she may be repeating this experience with a mutant of her own nine months down the road. To find such truly and legitimately powerful scenes slipped into the middle of a movie that spends so much time wallowing in triteness and facile stereotypes-- and in a fucking monster movie, no less-- is like having someone sneak up behind you and dump a bucket of ice-water on your head. I find myself asking, “If John Frankenheimer could do this, then what the hell was he doing during the rest of the movie?” I mean, was his deft handling of this subplot just a lucky accident, or what?

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact