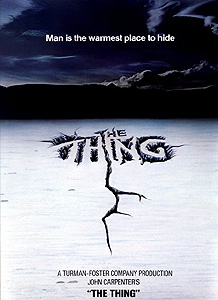

The Thing (1982)*****

The Thing (1982)*****

If someone were to ask me (not that anybody ever would) what I thought was the most misunderstood horror film of the 1980’s, I wouldn’t need more than a second to consider my answer: John Carpenter’s remake of The Thing. The professional, mainstream critics came down on The Thing like an imploding welfare high-rise the instant it appeared in theaters. “Gore for gore’s sake,” they said. “Nothing but one special effect after another,” they said. “No story, no characters, no soul,” they said. Hell, one reviewer went so far as to call Carpenter “a pornographer of violence!” And to my undying bewilderment, most of the hardcore horror and sci-fi fans seemed to agree. Like their more highly visible counterparts, they pointed to the version Howard Hawks and Christian Nyby had made back in 1951, and exclaimed, “Look, man— that’s how it’s supposed to be done!” No one seemed to realize that Hawks and company had taken an excellent pulp sci-fi story (John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?”), excised absolutely everything about it that had made it good in the first place, and built an enjoyable but extremely simplistic monster movie around the tale’s initial setup. To be fair, the Hawks-Nyby The Thing was the first of its kind, and introduced all of the tired old cliches that litter its every scene; it thus merits a fair percentage of the esteem in which it is conventionally held, as it is unquestionably one of the two or three most influential sci-fi/ horror films of its era. As an adaptation of its source, however, it is an utter failure, and “Who Goes There?” spent the next three decades just crying out for somebody to come along, make a movie out of it, and do it right. That is exactly what Carpenter did (although screenwriter Bill Lancaster plays with the details of Campbell’s story in several intriguing ways), and it pleases me to see that finally, after most of twenty years, this movie has started getting some of the respect it deserves. Having been staunchly in The Thing’s corner for about fifteen of those twenty years, I’d like to take a moment now to say, “I told you so.”

Right out of the gate, Carpenter lets us know that he will not be taking most of his cues from the 1951 version. There are no soldiers, reporters, or sexy secretaries here— just a helicopter with Norwegian markings pursuing a Siberian husky across the bleak Antarctic landscape. No explanation will be forthcoming for quite a while, but for some reason, the two men up in the helicopter really want to kill that dog. The man on the passenger’s side spends the whole flight leaning out the window with a semiautomatic rifle, taking potshots at the husky, and even goes so far as to toss hand grenades at it whenever the helicopter overtakes the animal before circling around for another pass. The Norwegian isn’t a very good shot, however, and his quarry eventually reaches the site of US Outpost #31, Station 4 of the United States Antarctic Research Institute. As the staff of the outpost wander outside to see what all the hoopla is about, the chopper lands, and its armed passenger disembarks, still intent upon killing the dog. Again, his efforts have little positive effect. In the brief interval before Station Manager Garry (Donald Moffat, from the ill-advised “Logan’s Run” TV series) shoots him in the face from the rec-room window, the Norwegian manages to wound meteorologist George Bennings (Peter Maloney, of The Children and Manhunter) in the leg and blow up his own helicopter by mistake. The put-upon husky, meanwhile, makes it safely into the custody of Clark (Richard Masur, from Nightmares and The Believers), the research station's dog handler.

The whole scenario is terribly odd. Atmospheric conditions prevent Windows the radio operator (Thomas Waites, of The Warriors) from reaching anyone in the outside world for advice or assistance, and barring the suggestion of camp cook Nauls (T K Carter) that “maybe we’re at war with Norway,” the only thing anyone can come up with to make sense of the strange attack is cabin fever. Even that explanation leaves a bit to be desired, however, for the Norwegians have apparently been in the field for only eight weeks. Dr. Copper (Prophecy’s Richard Dysart), the station’s physician, is concerned about the Norwegians; as he says, a man crazy enough to chase a sled dog all that way in a helicopter could do a lot of damage. Copper convinces the institute’s own helicopter pilot, R J MacReady (Kurt Russell, of Escape from New York and Big Trouble in Little China), to fly him out to the Norwegians’ campsite.

What they find there confirms the doctor’s worst fears and then some. Every building in the campsite has been burned down or blown up, their scorched and shattered interiors covered with slicks of frozen blood, but there’s a fair amount of evidence that the two men in the helicopter weren’t the sole cause of the damage. The first body Copper and MacReady stumble upon is clearly that of a man who took his own life— the corpse’s throat has been slashed, but it is still clutching a bloodied straight razor in its frozen hand. The mystery deepens further when MacReady discovers a huge block of ice elsewhere in the compound, a block which features an empty space in its center where something was obviously chopped out. Stranger still is what the two Americans find in a pile of charred rubble while returning to their helicopter. The burned remains are certainly those of a living thing, but neither man has any idea as to its species. What it looks most like is the bodies of several human beings that have somehow been fused together, but the patent impossibility of such a thing leads Copper and MacReady to discount that interpretation out of hand. Their scientific curiosity piqued, they bring the burned thing with them when they fly back to their camp, along with a ream or so of research notes and several hours’ worth of videotapes the Norwegians had made over the course of their expedition.

The moment he gets a look at the barbecued carcass Copper and MacReady have brought home, Garry orders head biologist Blair (Mr. Oatmeal himself, Wilford Brimley) to perform an autopsy. All Blair can tell his colleagues afterwards is that the dead creature is apparently human and apparently normal internally— which, needless to say, doesn’t go very far toward explaining it gross external abnormality. The solution to that mystery will have to wait for later that night, when Clark finally gets around to putting the Norwegian dog in the kennel along with his own huskies. As soon as their handler is out of sight, the dogs become extremely agitated, and begin barking furiously at their new kennel mate. And no wonder— the new dog undergoes an almost indescribable transformation and goes on the attack. Clark and MacReady both hear the dogs howling in pain and terror, and rush to investigate after tripping the fire alarm so as to awaken the rest of the men. Garry opens fire on the monster immediately upon seeing it, but neither his pistol nor the shotgun another of the men brings to bear seems to do much damage, and MacReady sends Bennings to fetch Childs the mechanic (Keith David, from They Live and The Puppet Masters) and one of the station’s two flamethrowers. Childs arrives just in time to witness the creature’s most disturbing trick yet; as he draws a bead on it with the flamethrower, the monster grows a pair of shockingly human-like arms, which punch through the ceiling, grab hold of the rafters, and haul half of its body to safety before Childs torches the rest of it.

This time, Blair’s autopsy is more informative. After dissecting the half of the creature that stayed in the kennel, he concludes that what he and his companions are dealing with is an organism that is capable of imitating any other species, and imitating it perfectly. So far as Blair can determine on the basis of the numerous half-formed dog carcasses that he found within the monster’s main body cavity, the creature has combined the functions of nutrition and reproduction. It somehow absorbs its prey, adds their biomass to its own, and then divides into several separate bodies (its own plus another for each of its victims) patterned after that of whatever organism it has just killed. Had Clark and MacReady not interrupted it, the men of US Outpost #31 would have had an entire pack of the things on their hands, and they would have been none the wiser.

The obvious question is, where in the hell did such a creature come from? Sure, it seems safe to conclude that the Norwegians cut it out of that block of ice, but how did it get there in the first place? As it happens, the videotapes Copper collected at the ruined camp hold the answer. They reveal that the Norwegians discovered some huge object buried under the ice a few miles from their camp, but accidentally blew it up while trying to melt it out with magnesium thermite. With the help of geologist Vance Norris (Charles Hallahan, from Terror Out of the Sky and Nightwing), Copper and MacReady find the place where the Norwegians had been working, and discover the wreckage of what can only be described as a flying saucer! (Naturally, there’s also a spot not far away where somebody had cut a big, rectangular block out of the ice.) According to Norris, the ice the ship was buried in should be about 100,000 years old.

Meanwhile, Blair’s been thinking about the monster, and he doesn’t like the conclusions he’s coming to one bit. Reasoning that the thing’s life cycle makes it more of a pathogen than a predator, Blair runs some computer simulations based on epidemiological models. If his computer is to be believed, there is a 75% chance that one of the men at the station has already been taken over by the alien. Even worse, the spread of the “infection” will be impossible to prevent in the event that the creature from space should make its way to a civilized area. In that case, the entire human population of the Earth would be assimilated and replaced within 27,000 hours of first contact. And if that’s so, then the perfection with which the alien duplicates its prey means that there’s only one way to avert such a catastrophe: neither Blair nor any of his colleagues can be allowed to leave Antarctica alive.

Rather than just diving right into why I think The Thing is such a fantastic film, I suppose I ought to take on each of the usual objections to it in turn. Let’s start with the “gore for gore’s sake” charge and its cousin, the “special effects über alles” complaint. This is a longstanding sticking point for me. Yes, The Thing is an extremely gory movie, and yes, the special effects are the most attention-getting thing about it. But in neither case can I understand how an attentive viewer can honestly contend that these features are gratuitous, or that they are the sole reason for the picture’s existence. The obsessive attention which both Carpenter and effects designer Rob Bottin devote to the monsters and their bloody transformations are absolutely necessary if this movie is going to do its job, which is to exploit the instinctive dread and visceral revulsion that most people feel toward biological contamination. If dueling life cycles is the name of the game, then it is essential that the viewer understand what the enemy life cycle is and find it as repellant as possible. The biology of the monster certainly is that, and the sheer energy of imagination that Bottin invested in his creations is stunning. It’s also light-years removed from James Arness in a bald cap, and I can see why people who walked into this film expecting something along those lines were taken so strongly aback. I also get the feeling that audiences— both lay and professional— would have been more comfortable had Carpenter and his accomplices cast the paranoia at the heart of the story in political terms, the way Hawks and Nyby had back in the 50’s. Critics, like most highly opinionated people, love to talk politics, and they’ve been having a field day with the Hawks-Nyby The Thing and its transparent ideological bent for more than 50 years. But this Thing isn’t a commie proxy. It’s a disease, and the paranoia it generates has less to do with the Red Scare than it does with the Black Death. And seeing as the early 80’s marked the beginning of the end for the triumphal advance of medical science (with the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria, exotic and incurable nightmare diseases like the hemorrhagic fevers, and AIDS, the Big Daddy of all the modern-day plagues), The Thing made its debut at a time when that kind of paranoia had an immediacy to it that fossil fears like communist infiltration couldn’t possibly match. At first glance, you’d expect it to have gone through the roof for that very reason, but remember that the early 80’s were also a time of vehement and emotional backlash against the transgressive pop culture of the preceding decade. By the time The Thing hit the theaters, mainstream audiences didn’t want to be made uncomfortable anymore; in that light, the genuinely appalled reaction that initially greeted it ought to be taken as the surest sign of its greatness.

As for the equally common complaints about the movie’s paucity of story and characterization, I can only answer, “you people just weren’t paying enough attention.” Admittedly, twelve major characters are a lot to keep track of, and the necessity of having them all clothed up to their eyeballs for much of the movie in virtually identical parkas doesn’t make the task any easier. And I concede that it never is made precisely clear just what functions some of the characters— Childs, Fuchs (Joel Polis), and Palmer (David Clendon)— perform at the station, or, for that matter, what kind of research the team is there to conduct in the first place. Those details really aren’t important, however, and there’s a difference between characters that are lightly sketched and characters that have no life to them. It never ceases to amaze me how efficiently the filmmakers— and the cast even more so— establish the web of relationships between the men of the outpost. With nothing but a line of dialogue here, a facial expression there, they set up a pattern of cliques, counter-cliques, friendships, and antagonisms that will be instantly recognizable to anyone who has ever spent much time in an all-male setting. (Incidentally, it occurs to me that the reviewers who take the most dismissive view of characterization in The Thing seem to be disproportionately female. This is probably not a coincidence.)

Furthermore, the story here is much smarter and more skillfully told than most critics give it credit for. None of the characters ever behaves in a manner that is less than credible, the movie never talks down to its audience in that way that horror and sci-fi fans know so well, and I can think of only one instance of questionable elements being introduced solely for the sake of plot convenience. (Just why would an Antarctic research outpost have a pair of flamethrowers lying around?) It’s also clear that Carpenter and Lancaster trusted their audience to do some thinking on their own, and were content merely to hint at some of the story’s more disturbing possibilities. For instance, what I find the most fascinating aspect of The Thing’s scenario is the one that has drawn the least attention— the question of whether an infected individual knows he has been taken over. Evidence repeatedly surfaces to suggest that the Things know who they are, but the filmmakers never come right out and say so, and they get tremendous mileage out of the fact that most of the uninfected characters have no real idea one way or the other. The issue comes out most strongly (although even here it is never explicitly acknowledged) during the scene in which MacReady forces everyone who remains alive at the station to submit to an improvised blood test designed to exploit the alien’s unique physiology. As each man’s turn comes up, it becomes obvious from the looks on most of their faces that they honestly aren’t sure what the results will be. This is another way in which this version of The Thing reveals its basis in the fear of disease rather than of consciously evil agency; the palpable relief of those men who are cleared by the test would be just as appropriate coming from somebody who has just received negative results in an HIV screening.

The parallels with virulent, lethal, and incurable disease also point toward the quality that I like best about The Thing. This was the first of the thematically related films that Carpenter sometimes refers to as his Apocalypse Trilogy: The Thing, Prince of Darkness, and In the Mouth of Madness. As befits an apocalyptic movie, The Thing is overlain by one of the strongest senses of inevitable doom that I’ve ever encountered. A conventional happy ending isn’t simply unlikely. Under the terms of the situation as the script has defined it, it’s categorically impossible— either it’s curtains for our heroes, or it’s curtains for the entire freakin’ world. And while it is true that the ending flinches just the tiniest bit from showing us one or the other of those possibilities directly, it could scarcely be called any less bleak for showing such restraint. I doubt that I could think of a much sharper a contrast to the “Through vigilance we will prevail!” coda of the 1951 version. The grim, hopeless tone is this movie’s one major departure from the spirit of the tale on which it is based, but to me, such a handling follows more naturally from the subject matter than either the confident determination of the earlier film or the guarded optimism of “Who Goes There?,” and gives Carpenter’s adaptation the greatest impact of the bunch.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact