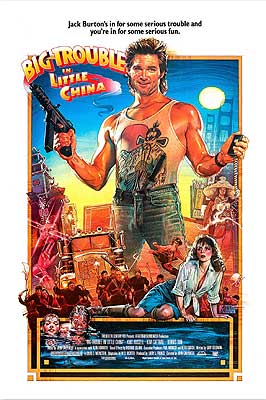

Big Trouble in Little China (1986) ***½

Big Trouble in Little China (1986) ***½

I didn’t actually plan it this way, but I’m going to pretend that this here review is my own little private fifteenth anniversary party for the B-Masters Cabal. That’s because I can’t believe that not one of us, past or present, has covered Big Trouble in Little China in all that time. It’s one of the key cult movies of the 1980’s, and it seems tailor-made for the tastes of several of our most prolific members. Yet somehow it falls to me to be the first, fully a decade and a half into the Cabal’s existence. So happy fifteenth, my fellow B-Masters. Is that the Anniversary of Being Cut to Pieces, or the Anniversary of the Upside-Down Sinners?

Long-haul trucker Jack Burton (Kurt Russell, of Stargate and The Deadly Tower) arrives in San Francisco’s Chinatown with a trailer full of live chickens and yearling pigs for the enclave’s restaurants and grocery stores. Presumably this is a frequent run for him, since he’s dubbed his rig the Porkchop Express. Once all the deliveries are made, he meets up with his friend, Wang Chi (Dennis Dun, from Warriors of Virtue and Venus Rising), the proprietor of a Cantonese eatery called Dragon of the Black Pool. The two men spend the whole night gambling at some Chinese domino game, and Jack’s run of luck is unbelievable. Come sunrise, he’s taken Wang for more than $1100, and a final, foolish double-or-nothing wager on Wang’s part goes Jack’s way, too. Unsurprisingly, Wang doesn’t have $2200 on him, and despite all the years of their friendship, Jack doesn’t trust him far enough to let him out of his sight for a moment until he pays up. Thus it is that Jack ends up giving Wang a lift to the airport— which is how the titular Big Trouble begins.

The reason Wang needs to be at the airport this morning is because his fiancee, Miao Yin (Suzee Pai), is flying in from Beijing to consummate their long engagement. He’s obviously pretty smitten with the girl, since he won’t stop talking about her during the drive to San Francisco International. One detail that seems especially to obsess Wang is the color of Miao Yin’s eyes— but considering how rarely one encounters a Chinese with green eyes, I suppose the fixation is somewhat justified. Less recognizable is the reason for a fixation that comes over Jack at the airport, where he spots an admittedly attractive blonde woman whom Wang identifies as Grace Law (Kim Cattrall, from Good Against Evil and Star Trek VI: The Undiscovered Country), a civil rights attorney specializing in issues of concern to San Francisco’s Chinese community. She too is here to pick up a girl from the old country, although Grace’s is apparently a fugitive from a sex-trafficking ring. Maybe that explains what three members of the Lords of Death— Chinatown’s most vicious street gang— are doing prowling around the arrivals pier. Sure enough, the mobsters pounce on Grace’s client the moment she emerges from the press of the crowd, but they didn’t figure on Jack Burton. Okay, so his intervention nearly gets him killed, as he proves wholly unequal to the challenge presented by three hardened criminals trained in kung fu. He does, however, cause the Lords of Death to abandon their bid to abduct the girl Grace is trying to protect. Alas, that just pushes them to make off with Miao Yin instead.

Wang and Jack give chase, of course, all the way back to Chinatown. Things take a turn for the truly weird, though, once they’re back in familiar territory. Pursuing the Lords of Death down an alley close to their home base, Jack and Wang run straight into a Tong funeral, as the members of the Chang Sing organization march the coffin of their recently deceased leader through the streets of Chinatown. The Chang Sing look fearsome, but Wang assures Jack that there’s nothing to worry about from them. However, the same is manifestly not true of a rival Tong group called the Wing Kong, whose soldiers suddenly fill up the alley from behind Jack’s truck, brandishing guns and twirling meat cleavers. The next thing Wang and Jack know, they’re in the middle of all-out war between the Tong factions, and the Lords of Death slip away in the confusion. Still, the Chang Sing appear to be pulling ahead in the fighting, so maybe Miao Yin’s would-be rescuers will get out of this okay after all. That’s when the Three Storms arrive. This aptly named bunch consists of three brothers dressed for a wuxia epic, whose kung fu confers upon them control over rain (Peter Kwong), thunder (Carter Wong, of The 18 Bronzemen and The Fatal Flying Guillotines), and lightning (James Pax, from Remains of a Woman and Dragon Chronicles: The Maidens of Heavenly Mountains) respectively. Evidently the Storms are friends of the Wing Kong, too, because they immediately set about slaughtering the Chang Sing. Jack rather sensibly panics at that point, and hits the gas. In doing so, he drives his truck straight over a towering, gaunt man (James Hong, from Blade Runner and Ninja III: The Domination) clad in the silken robes of an ancient Chinese nobleman. Alarmingly, the victim of Jack’s carelessness seems only mildly inconvenienced by being thus flattened. Now it’s Wang’s turn to panic, because he knows who the invulnerable mandarin is: Lo Pan, the legendary foe of China’s first Sovereign Emperor and master of the Three Storms. This is no time or place to tangle with the most powerful evil ghost in mainland East Asia, nor even to ask what he’s doing in Chinatown instead of, you know, China. Unfortunately, there’s also no room left for Jack’s truck to maneuver in the alley, so he and Wang are forced to flee on foot. When they return to the alley after waiting out the rest of the battle, the Porkchop Express is just as gone as Lo Pan, the Tongs, the Storms, and the Lords of Death. And so, in case this weren’t already obvious, is Miao Yin.

Later, at Dragon of the Black Pool, Wang, Jack, and Wang’s Uncle Chu (Chao Li Chi, of Archer: Fugitive from the Empire and The Big Brawl) plan their next move— or rather, Wang, Chu, and Eddie Lee (Deep Core’s Donald Li), the new maitre-d at the restaurant, plan the next move while Jack wrangles over the phone with his insurance company. Grace Law drops in, too, bearing scuttlebutt to the effect that the Lords of Death have sold Miao Yin to the notorious sex-slaver known as the White Tiger (June Kyoto Lu, from Lady in the Water and Confessions of an Opium Eater). It’s a safe bet they’re looking to sell Jack’s truck, too, but that’s a bit outside Grace’s area of expertise.

Obviously a visit to the White Tiger’s brothel is in order, but any such venture will require great care and a good cover story. Eventually, the prospective heroes settle on the following scheme: Jack is to pose as a sleazoid idiot seeking to hire a girl meeting Miao Yin’s description, while Wang, Grace, and Eddie wait outside in the latter’s Cadillac (the conspicuousness of which makes it maybe not the best choice as a getaway car). Once Jack has Miao Yin alone, he’ll explain the situation, and they’ll sneak out of the building together. This sensible-sounding plan hits a snag, however, when the Three Storms literally blow the roof off the whorehouse, and subject Miao Yin to her second kidnapping in 24 hours.

Now you might ask what Lo Pan— someone whose merest whim can banish an enemy to one of the many Chinese Hells— could want with the fiancee of a Chinatown restaurateur, but remember those green eyes Wang finds so enchanting (and which the White Tiger was counting on to set Miao Yin’s hourly rate in the stratosphere). When Qin Shi Huang, the aforementioned First Sovereign Emperor, defeated Lo Pan 2000 years ago, he called upon Ching Dai, God of the East, to curse the villain with his current deathless-yet-fleshless state. But if Lo Pan marries a girl with green eyes and then sacrifices her to the spirit of Emperor Qin, he can break the curse, regain his mortal body, and paradoxically acquire along with it the power to rule the universe. Right. So obviously it would behoove Lo Pan to keep his ear to the ground for any rumors of a green-eyed girl appearing on Chinatown’s prostitution market, and when you’re an immortal undead sorcerer, you tend to consider yourself above the need to pay for things. Rather surprisingly, it’s Grace who makes the connection between Miao Yin’s abduction by the Three Storms and Lo Pan, but it turns out the warlock is preceded by several reputations. Grace knows him as David Lo Pan, chairman of the National Orient Bank, owner of the Wing Kong Exchange trading company, and foremost gangster in Chinatown, and neither she nor her journalist friend, Margo Katzenberg (Kate Burton), can contain herself at the thought of publicly linking him to international sex trafficking.

Again the name of the game will be do-it-yourself covert ops, with Wang and Jack infiltrating the headquarters of the Wing Kong Exchange (which, by the way, is indeed Wing Kong as in the cleaver-twirling Tong army) by impersonating building maintenance contractors. Meanwhile, Uncle Chu calls in Egg Shen (Victor Wong, from Tremors and Prince of Darkness), the dotty-seeming old man who drives the Egg Foo Yong Tours bus around Chinatown. The latter man may sound like an odd choice of allies under the present circumstances, but all the locals recognize that no one in the neighborhood knows more about ghosts, demons, magic, and the like than Egg Shen. It’s Egg who explains to Grace what Lo Pan really is, and to her credit, she takes it completely in stride. But if Lo Pan is as powerful as the bus-driving peasant wizard says, then Wang and Jack are in fathoms over their heads. Indeed, the two men have just barely penetrated the distinctly weird inner sanctum of the Wing Kong Exchange when they are captured by the Three Storms. Grace, Eddie, and Margo’s rescue mission doesn’t go any better, but Wang and Jack are able to exploit Eddie’s arrival in their holding cell to break out, and launch a raid on the kennels where the Wing Kong keep the girls they import from overseas. Miao Yin isn’t in any of those cages, but Grace and Margo are. The ensuing escape attempt comes within a hair’s breadth of total success— that hair being Grace, who gets snatched up at the last minute by one of Lo Pan’s demons.

Clearly it’s long past time to take off the gloves. The next time Wang and Jack go into the Wing Kong Exchange, it’ll be no small-scale commando raid, but a full-on assault. Egg Shen will be along with his six-demon bag (“What’s in it, Egg?” “Wind. Fire. All that kind of thing!”) and a magic potion conferring the ability to see things no one else can see and do things no one else can do. They’ll have the full remaining force of the Chang Sing at their backs, too, and they’ll be coming in super stealthy-like, through a secret underworld beneath Chinatown known only to its most mystically-inclined residents. There’s a new wrinkle to the situation, though, that not even Egg Shen has foreseen. Grace Law’s eyes are just as green as Miao Yin’s, and Lo Pan has decided to marry both women, doubling his chances of breaking the curse.

If any American-made movie more accurately captures the flavor of Hong Kong fantasy action cinema than Big Trouble in Little China, I don’t know what it might be. The speed, the energy, the complexity of plot, the audacity with which seemingly incompatible elements are thrown together and made to work anyway— it’s all here. That would be an impressive enough accomplishment all by itself, but director John Carpenter goes further, combining that unexpectedly authentic Hong Kong sensibility with, of all things, a tribute to the style of Howard Hawks and an inversion of one of Hollywood adventure film’s most basic tropes, doing it all with a wit that manages to be both dry and campy at the same time. It’s kind of a mad project when you look at it in the round, and it’s little wonder that Big Trouble in Little China took years to find a properly appreciative audience.

I know that when I first saw this movie in my early teens, soon after putting two and two together to realize that John Carpenter was the guy who made both Halloween and The Thing, I was completely baffled by it. What I didn’t grasp until much later was that it’s supposed to be baffling, partly because that’s how the Asian films that inspired it often come across for Western viewers, but also because we’re seeing the story unfold mainly from Jack Burton’s perspective. As Burton himself puts it, that means the perspective of a reasonable guy who has just seen some very unreasonable things. Or alternately, we could use Lo Pan’s formulation of the same idea: “You were not brought upon this world to ‘get it,’ Mr. Burton.” (Have I mentioned yet that Big Trouble in Little China’s dialogue is almost infinitely quotable?) When the plot moves too fast to be followed in real time; when five new unexplained things crop up for every one that we succeed in making sense of; when there’s nothing we can do except to forgo asking for exposition or justification, and just float along with the current of the story— then we’re experiencing the same disorientation as Jack himself.

That’s central to the trope-flipping I mentioned earlier, because although Jack may be the viewpoint character in Big Trouble in Little China, he only thinks he’s the hero. This is the third consecutive update in which I’ve covered a movie that played that trick, but Big Trouble in Little China is different because its creators fully understood what they were doing, and fully explored all the implications of focusing on the sidekick’s point of view. At first glance, it resembles an old-fashioned “white guy saves the day” Yellow Peril movie, and golden-age Hollywoodisms like the Hawksian dialogue, a climax hinging on a coerced wedding between the villain and the heroine, and Jack Burton’s cowboyish persona encourage us to stick with that impression. But as the film progresses, it becomes increasingly obvious that Jack isn’t the one saving this particular day after all. Burton underestimating the Lords of Death at the airport is the kind of thing that could happen to any novice hero, but a typical action movie bad-ass would level up from there. Jack doesn’t. By the time he begins his contribution to the climactic battle by knocking himself unconscious, you’ll be impressed that he manages to tie his own moccasins all by himself. (Somehow I don’t think bringing that rain of debris down on his own head was quite what Egg Shen had in mind when he said the magic potion would let Jack do things no one else can do…) When Burton does contribute meaningfully to defeating Lo Pan, it happens essentially by accident— and incidentally turns Jack’s self-aggrandizing refrain of “It’s all in the reflexes” into one of the movie’s best and subtlest punch lines.

Meanwhile, Wang Chi, who by Hollywood convention has “Sidekick” written all over him, kicks ass and takes names all throughout the film. Wang knows what’s going on every step of the way. Wang defeats whole squads of Wing Kong soldiers singlehanded while Jack is scrambling to retrieve a knife that he accidentally threw across the room. Wang has the band of powerful and fiercely competent allies, Wang has the well-earned self-assuredness in the face of immense danger, and let’s not forget that it’s Wang’s girlfriend who motivates the story by getting captured in the first place. He is, by any imaginable definition, the hero of Big Trouble in Little China. Carpenter seems, however, to have underestimated the pull of the clichés he was playing with, and to have failed to appreciate how uncritically the average viewer would accept Jack’s own assessment of his place in the story. Certainly Carpenter’s handlers at 20th Century Fox missed the point by a mile, which is why the final cut includes that odd prologue with Egg Shen talking to the city attorney, harping on the Chinatown residents’ gratitude and sense of indebtedness toward Jack. This was the era of Stallone and Schwarzenegger, Bronson and Eastwood, Norris and Dudikoff; perhaps no one should be surprised that American audiences weren’t prepared for a comedy action fantasy in which the Chinese second banana is really the hero, while the top-billed white guy plays an extremely courageous man who isn’t actually good for much of anything.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact