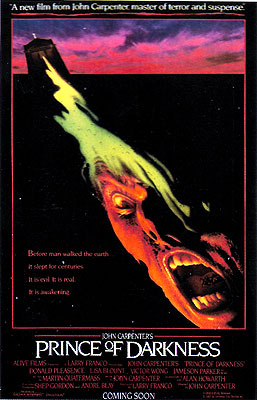

Prince of Darkness (1987) **½

Prince of Darkness (1987) **½

John Carpenter’s Prince of Darkness is not a movie for thirteen-year-old boys, which is part of what makes it so exceptional among the horror films of 1987. I mean, while the rest of the industry was mostly content to scrape the bottom of the slasher barrel or maybe to rip off Evil Dead II, Carpenter marked his return to independent filmmaking (following four years of increasingly exasperating work for the major studios) with an elliptical, cerebral picture inspired equally by Nigel Kneale and H. P. Lovecraft, which recast the normatively supernatural story of the rise of the Antichrist in purely science-fictional terms. Unfortunately, when I first saw Prince of Darkness, I was a thirteen-year-old boy, and consequently did not get it at all. So I’m sure you can understand why, of all the movies I watched back then, but haven’t seen since, this is the one regarding which I trusted my old memories the least. Nevertheless, that sensation of grumpy bewilderment stuck with me, to say nothing of the largely negative reactions of contemporary fans and critics, and I remained in no great hurry to revisit Prince of Darkness even as its reputation steadily improved. Come on, though. I’m 41 fucking years old now— if I’m still not mature enough to handle this movie, then it’s unlikely I ever will be. Furthermore, I’ve seen Five Million Years to Earth, I’ve gotten over the worst of my disdain for Lovecraft, and I’ve read enough about what Carpenter was trying to do here that I should certainly able to keep from getting lost. It’s long past time for me to suck it up and give Prince of Darkness another try.

Seven million years ago, a star seven million light years away blew itself to bits. That, of course, means that its death throes are due to become visible from Earth right… about… now. In the wake of the supernova, small outbreaks of weirdness begin happening all over the Los Angeles neighborhood where stands a certain dilapidated Catholic church: frenzied behavior among insects and other vermin, a zombie-like purposefulness coming over the local population of the homeless and insane, that sort of thing. The elderly and infirm priest who runs the church in question dies, and his successor (Donald Pleasance, of Vampire in Venice and From Beyond the Grave) inherits a mystery along with his new office. There’s something in the basement, you see. The foundation of the church is much older than the building currently standing on it, dating all the way back to Spanish colonial times, and within it are housed a book written in an indecipherable jumble of ancient languages and the biggest, spookiest Lava Lamp you ever saw. The dead priest’s diary explains that the site belongs to a secret appendage of the Catholic Church called the Brotherhood of Sleep, and that their job was to watch over the two artifacts while making sure that nobody on the outside ever found out about them without proper authorization. Apart from that, the new custodian of the relics is pretty much in the dark. Most everything that has ever been known about the big canister of swirling, green fluid is contained in the unreadable book, and all he can glean from the diary is that the stuff inside the Lava Lamp is both apocalyptically bad news and also in some sense alive. So Father Whatshisname does the only sensible thing under the circumstances, and calls for backup.

Backup in this case means theoretical physicist Harold Birak (Victor Wong, of Big Trouble in Little China and Tremors), whom the priest met some years ago when they both participated in a series of lectures and debates sponsored by the professor’s university. Together with his colleague, Dr. Paul Leahy (Peter Jason, from The Amazing Captain Nemo and Streets of Fire), Birak puts together an eclectic team of elite grad students— aspiring physicists, chemists, biologists, mathematicians, linguists, cryptologists, computer programmers, and who knows what else— to study the priest’s relics, and with any luck to figure out just what in the hell they are. The team’s discoveries are disquieting, although some of the researchers, most vocally Walter (Warriors of Virtue’s Dennis Dun, also returning from Big Trouble in Little China) and Wyndham (Robert Grasmere, who shows up briefly in Demolition Man and They Live), don’t entirely believe their own findings. Analysis of the corrosion on the canister suggests a seemingly impossible age of seven million years. (Hey! Just like that supernova!) Kelly (Susan Blanchard) determines that the artifact has a complex locking mechanism operable only from the inside. The computer program that Catherine (Lisa Blount, from Dead & Buried and Nightflyers) sics on the text of the book uncovers a huge and involved body of differential equations encoded into it, despite the fact that it was written more than 1600 years before the invention of calculus. And as Lisa (Ann Yen) translates the book, a story emerges corroborating the vague alarmism of the dead priest’s diary. If the ancient tome is to be believed, the liquid inside the canister is the being that Christianity calls Satan, bottled up for safekeeping by its father, the Anti-God, when the latter was driven out of our universe seven million years ago. At one point— this would have been about AD 30— an extraterrestrial being visited Earth to warn us of the peril that would soon be upon us (for cosmic values of “soon,” anyway), but the authorities of the time didn’t feel like listening to him, and his human followers for the most part completely misinterpreted what he was trying to tell them. The few who understood founded the Brotherhood of Sleep, but were quickly subsumed by the misguided cult that became the Roman Catholic Church. And now it’s too late to heed any warnings. The supernova has awakened the spawn of the Anti-God, and neither Jesus nor “the God Plutonium” (to quote my favorite line in the whole film) will save us.

Okay. But what exactly won’t they save us from? What kind of power does a can of old glop really have? Well, we already know it can control the behavior of bugs, worms, and crazy people. In practice, that means Birak and his team quickly find themselves pinned down inside the church by a platoon of deranged bums led by Alice Cooper (whose other dabblings in acting include Freddy’s Dead: The Final Nightmare and Monster Dog). And as Susan (Anne Marie Howard, from The Collection and Lost Signal) is the first of the researchers to discover, a devil doesn’t need horns or a pitchfork to wield the traditionally Satanic power of possession. In fact, it might even be easier for a liquid devil to possess people, since it can just squirt some of itself into whichever bodily orifice a potential victim makes handy. Nor, as it turns out, need the victim be alive for possession to take hold— so I guess Prince of Darkness has just a little bit of Evil Dead in it after all. And last but not least, this devil resembles the standard model in its desire to knock up humans in order to create hybrids more powerful than the zombie-like beings that possession yields. However, infernal pregnancy in Prince of Darkness works rather differently than we’re used to. Instead of Kelly giving birth to a baby Antichrist, she somehow absorbs the full power of Lava Lamp Satan into herself so as to become the incarnation of evil. It isn’t quite clear what that incarnation will do if given the chance, but to judge from the vague dreams of the near future that everyone working in the church has whenever they fall asleep during the ensuing night, I’m sure it’s nothing that humans are going to like.

Well, that certainly was a letdown. The snarky tone of my opening paragraph notwithstanding, I revisited Prince of Darkness fully expecting to get it this time, not merely in the sense of understanding what was going on, but in the deeper sense of appreciating it as the ambitious, sophisticated horror film that increasing numbers of fans now recognize it to be. Prince of Darkness surely is both ambitious and sophisticated, despite hailing from an era that had little patience for or interest in either of those qualities, and it deserves some respect because of that alone. It features a couple of great performances, too, most of all Victor Wong’s as a scientific answer to the Chinese folk magician he played for Carpenter the year before. However, this film is also unfocused, limply paced, and kind of boring, nor does it ever find a convincing way to articulate its creator’s notion of naturalizing the supernatural through the insights of quantum mechanics.

With regard to focus, the principal trouble is Carpenter’s Michael Mann-like failure to appreciate just how deeply in the dark the audience would be when he handed them a can of Mountain Dew and told them it was the Devil. I can see why he wanted to steer clear of a standard-issue Satan in this of all movies, but the advantage to using one is that we’d all grasp at once what the stakes of the story were just by cultural osmosis. By making Satan a vat of green liquid, Prince of Darkness cues us to discard everything we think we know about him, but we need something to put in place of the conventional understanding. If this devil isn’t the one we know, then what is it instead? Carpenter isn’t telling. Indeed, all we ever learn about the agenda of his Satan is that it’s bad enough for people in 1999 to rig up a tachyon television dream transmitter in the hope of motivating the past to take action. Don’t bother asking how they managed that, though— and don’t bother asking what’s so special about 1999, either. My best guess is that it’s a lazy reference to the crudely literal school of thought, common at the time, which held that the big-M Millennium would begin at the turn of the little-m millennium, but a guess is all that is. Even at the climax, there’s no clear sense of what specifically is supposed to be happening. All we can say is that Antichrist Kelly needs a big-ass mirror to serve as her portal to somewhere. So— what? She’s going to come back in twelve years with a trained Jabberwock at her side?

That lack of clarity combines with the sleepy pace to sabotage all of Prince of Darkness’s efforts at being scary. With the true nature of the threat this obscure, the film is unable to avail itself of Alfred Hitchcock’s famous bomb under the table, and few of the characters seem much more than intellectually offended at how the relics in the church keep violating their tidy models of how the world is supposed to work. If they’re not frightened, why should we be? This might actually be a case of Carpenter’s Lovecraft getting in the way of his Kneale, because old Howie was all about scholars sitting around learning things they didn’t want to know. Meanwhile, the quantum mechanical apocalypse, whatever it may be, stands on the sidelines glancing irritably at its atomic watch.

The more I think about it, the more convinced I become that the repeated invocation of quantum mechanics is where Prince of Darkness gets most seriously lost in the weeds. Carpenter had recently become fascinated with the subject, and I can see what he was trying to do by building a horror movie loosely around its concepts. It can indeed be pretty unsettling to contemplate that subatomic reality works so differently from the reality that we experience that it can be described only probabilistically. Hell, quantum mechanics is downright Lovecraftian, if you look at it from the right angle. Why not use it to give substance to a film about Newtonian-scale reality breaking down under the influence of otherworldly forces? The thing is, that’s a trick question. The reason you shouldn’t do it is because what quantum mechanics actually does is to give us a basis for dealing rationally with a setting where ordinary rationality doesn’t apply. Quantum mechanics tames the apparent breakdown of reality, turns it into something measurable, quantifiable, understandable. Compare Prince of Darkness to something like Demons, The Gates of Hell, or The Beyond. Those movies are genuinely irrational, and they’re disturbing because of it. This one wants to elicit the same response, but it keeps showing us the protagonists figuring shit out. The Unknown stops being as scary when you reframe it as the Stuff We Don’t Know Yet.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact