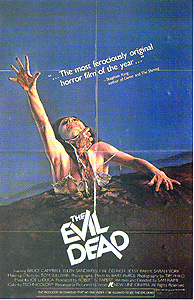

The Evil Dead (1982) ****

The Evil Dead (1982) ****

I grew up at a momentous time for fans of exploitation movies— for fans of exploitation horror movies especially. True, the drive-in was in its final decline, the 42nd Street grindhouses were being exterminated by the escalating efforts to clean up Times Square, and the companies that had produced the great trash classics of the 50’s, 60’s, and 70’s were dying off like megafauna after an asteroid strike, but there were two major countervailing developments that made the 80’s a great time to harbor my obsession. First of all, there was cable television; secondly, there was home video. Between them, cable TV and the VCR increased the accessibility of bottom-feeding film to a degree that would have seemed impossible in earlier eras. With cable, TV viewers no longer had to settle for the FCC- and Standards and Practices-approved neutered versions of movies like It’s Alive or The Howling, and if they were willing to stay up super-late, it was possible to see things the broadcast stations wouldn’t have touched in even the most piteously bowdlerized forms; for a really extreme example, consider that it was on cable that I first encountered Don’t Go in the House and Ms. .45! Home video broadened the horizon even more, in that it freed you from the vagaries of the programming schedule. The only limit on what you could watch at any given time was the selection offered by your neighborhood rental shop, and my readers who weren’t around for those days might be amazed at what even the big chains were willing to carry. Believe it or not, the first Blockbuster Video to open up within easy driving distance of me had Street Trash, Orgy of the Dead, and The Wrestling Women vs. the Aztec Ape on its shelves. Naturally, the self-appointed defenders of morality had a hard time accepting all that quality schlock falling within easy reach of us kids, and there was eventually a backlash. But nothing we faced in the United States holds a candle to what our cousins across the Atlantic had to deal with. While we were worrying about newspaper columnists, TV preachers, and horrified grandmothers convincing our parents to confiscate our rental cards, and grumbling about how much harder a low-budget horror movie had to work now to avoid an X-rating, horror fans in Great Britain were standing at ground zero of the Video Nasties panic.

At first, remember, the big movie studios were terrified of home video. Instead of a huge new market, all they could see for the first few years was an open invitation to piracy. Consequently, there was a serious shortage of mainstream product for video distributors to sell, so they turned to decidedly non-mainstream sources to fill out their catalogues. Things were arguably even worse in Britain, since a Hollywood studio looking to enforce its licensing prerogatives would have to contend with a foreign legal system on top of all the other uncertainties of the situation. It was thus understandable that British distributors, like their American counterparts, would end up buying the rights to huge numbers of independently produced movies from all over the world, and the economics of independent film being what they were, it was also understandable that a large proportion of those titles would be exploitation pictures. There was another way, too, in which the British experience in the early days of home video was like the American, only more so. Just as in the US, the agency charged with policing the content of movies released into theaters had no jurisdiction over home video, but because the British Board of Film Censors was at least in some sense a government regulatory body, the authority vacuum in the new industry seemed much more dangerously anarchic to the Brits than it did to Americans, whose MPAA ratings board was nothing more than a manifestation of industry self-censorship, and who had always been far more accepting of cinematic gore and violence in the first place. With no constraints on their behavior save the unwieldy and antiquated Obscene Publications Act, British video distributors imported uncut versions of foreign horror films that never would have passed BBFC muster. What’s more, they were outright boastful about it, employing the most lurid, sleazy, sensational advertising they could contrive, essentially trumpeting to the consumer, “Check it out! Here’s all the stuff you’re not allowed to see in the theaters!” The backlash in Britain was sharper by orders of magnitude than that in the United States. Right-wing tabloids like the Daily Mail ran scandal-mongering stories about “violent pornography” and “snuff films,” eventually coining the term “Video Nasties” to describe the appalling filth in which the nation’s video hire shops were supposedly awash from floor to ceiling. The National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association raised a louder and more sustained ruckus than they had about anything in many years. The Director of Public Prosecutions went on the attack with a ferocity matched only by the incompetence of his minions. Finally, in 1984, Margaret Thatcher’s Parliament weighed in with the Video Recordings Act. The BBFC’s authority was extended to cover home video, and the agency was given statutory (as opposed to merely regulatory) power for the first time in its history. Most significantly, a timetable was set up according to which all movies in circulation on home video would have to be submitted for BBFC certification, and all copies of those which were not passed in their current form withdrawn and replaced with the approved version. In the end, nearly 40 formerly available films were banned completely in the wake of the Video Recordings Act, while countless others were trimmed down until they were nearly as lifeless as the versions you could see on American broadcast television.

By any fair assessment, the vast majority of the horror movies that got snagged in the Video Nasties dragnet were indeed utter garbage, relying for their profitability upon their appeal to an audience (you and me, for example) that revels in the poorest possible taste. There were a few, however, that have come to be regarded as classics in the twenty-odd years since then, and Sam Raimi’s The Evil Dead is almost certainly the foremost of that lot. This is not to say that bad taste isn’t an extremely important element of The Evil Dead’s modus operandi, but a good gross-out is the least of its charms, and even when The Evil Dead does wallow in studiedly nauseating gore, writer/director Raimi makes smarter and more effective use of it than nearly anyone else in the business.

There appears to be some sort of law in force requiring anyone who reviews The Evil Dead to open their synopsis by commenting upon what a cliché the movie’s setup is. There is a certain amount of truth in that conventional lead-in, but it must be borne in mind that the group of college kids meeting a grisly fate while on a vacation in the woods was at least a living commonplace in 1982. More importantly, it seems to have been Raimi’s avowed aim to achieve something extraordinary by recombining the rudiments of his era’s most profitable horror subgenres in a novel and exciting way. In any case, the doomed vacationers are Ash (Bruce Campbell, later of Moontrap and Bubba Ho-Tep), his girlfriend Linda (Betsy Baker), his sister Cheryl (Ellen Sandweiss, who sadly would not be seen again until Satan’s Playground more than twenty years later), their friend Scotty (Crimewave’s Hal Delrich), and Scotty’s girlfriend Shelly (Sarah York). We meet them as they’re driving into the Tennessee woods in Ash’s ‘73 Oldsmobile (a car which can be seen at least briefly in nearly every movie Sam Raimi has ever made), with the intention of staying for a few days at an isolated cabin which Scotty has arranged to rent. The movie has literally just started, and already Raimi is showing us hints of what a horrible plan this is. As per usual, there’s a POV cam prowling around in the woods, but in contrast to the typical woodland slasher flick, there is simply no way these shots represent the perspective of a human being, no matter how demented or depraved; rather than proceeding haltingly at a man’s eye-level, this POV cam glides rapidly through the woods at perhaps two or three feet off the ground, and it is always accompanied by an unearthly and almost indescribable rumbling sound. As a further ominous touch, when the campers arrive at their cabin, they are greeted by the menacing rhythmic thud of the glider on the front porch banging against the outer wall, despite there being no evidence of wind otherwise. The glider’s swinging stops abruptly the moment Scotty retrieves the keys to the cabin from the hook above the front door.

The weirdness at the cabin only grows more intense and more threatening from there. Shortly after dark, while Cheryl is sitting alone in the front room, sketching the clock on the wall, the pendulum seizes up at the top of its arc, and the clock starts chiming even though the hands aren’t pointing toward any remotely round fraction of an hour. A powerful wind gusts through the open window, and Cheryl’s hand begins convulsively scratching out a crude drawing of a rectangular object with a hint of human facial features on its upper surface. The last thing to happen before the manifestation ends is a booming voice from outside intoning, “Join us.” Later, while the kids are eating dinner, something kicks open the trapdoor to the cellar. There’s no sign of anything living in the surprisingly vast basement when Scotty and Ash go to investigate, but there is a great deal of curious inanimate stuff down there. In addition to a shotgun, a reel-to-reel tape recorder, and a one-sheet for The Hills Have Eyes, the boys uncover an apparently ancient dagger with a hilt that might have been designed by H. R. Giger and a book that looks suspiciously like the object Cheryl drew during her trance. Scotty and Ash bring their discoveries upstairs, and on a lark, the kids decide to play the tape threaded through the recorder. It’s a diary of sorts, describing how an unnamed archaeologist excavating the ruined Sumerian city of Kandaar unearthed the book and the dagger, and then retreated to the cabin in order to study them in peace. The recorded diary identifies the book as the Noturon Demonto, the Sumerian book of the dead, and from what the professor has been able to determine, it contains incantations which are supposed to be able to summon forth undying evil spirits and give them license to possess human beings. Cheryl wigs out, demanding that somebody turn off the machine, but Scotty lets it run until after the part where the archaeologist recites an incantation from the book.

That, as if you couldn’t guess, signals the beginning of the end for our heroes. Cheryl continues to hear strange, voice-like sounds from the woods outside, and when she foolishly goes to track down the person she believes is making them, she is seized and pinned down by vines and tree branches, and raped by some sort of root! Cheryl breaks away and flees to the cabin, but something that apparently only she can see pursues her. Oddly, it doesn’t force its way into the cabin when Ash opens the door in response to his sister’s frantic pounding, but retreats into the forest. Cheryl, understandably, has had enough at this point. She harangues Ash into driving her back into town, but escape isn’t going to be that simple. In order to get to the cabin, Ash and his friends had to drive over a rickety old bridge across a sheer-sided ravine, and there’s nothing left of that bridge but a few tattered, rusty girders when Ash and Cheryl reach it going the other way. Back at the cabin a short while later, whatever entered the girl’s body when she was raped by the forest takes control of her, turning her into a vicious and inhumanly strong zombie-like monster. Scotty and Ash between them are able to force Cheryl down into the cellar and lock the trapdoor above her, but not before she stabs Linda through the ankle with a pencil. As the night wears on, the spirits awakened by the taped incantation will claim the remaining campers one by one, and though a serious wound from the Sumerian knife seems to be able to de-animate the possessed undead temporarily, the only way to destroy them is to hack them limb from limb.

That hacking limb from limb goes a long way toward accounting for The Evil Dead’s presence on the Video Nasties list. I had forgotten what an exceptionally grotesque movie this was, and in the old VHS edition from the 80’s, the relatively poor image quality has the effect of rendering the abundant gore utterly convincing. (In the more recent digitally remastered versions, both VHS and DVD, the sharper, cleaner picture unfortunately makes it much easier to spot the shortcomings of the low-budget makeup effects.) This is an important point of contrast with such later overkill-laden zombie films as Dead Alive or indeed Evil Dead II, in which the gore effects are deliberately stylized to one degree or another; unlike so many of its successors, The Evil Dead wants you to take its violence seriously.

In fact, the greater seriousness as compared to subsequent gore films extends to pretty much everything about The Evil Dead. Though it is frequently described as at least part comedy in more recent video guides, the authors of those guides are almost certainly allowing the knowledge of this movie’s sequels to color their impressions of the original. There is almost no humor as such in The Evil Dead, even in scenes like the root-rape, which would most likely be played for queasy laughs in a horror film of today. And it is for precisely that reason that this first film in the series remains my favorite, even though both of its sequels are substantially superior in most technical respects. Ash may be as much of a cypher as the more expendable characters, Bruce Campbell and Ellen Sandweiss may be the only cast-members capable of anything even resembling acting, and the story may be weighed down by countless minor idiocies and lapses of logic, but damn it, this is a horror movie that means it! And it is a horror movie that gets it right more often than not. For all the spurting blood and flying giblets, The Evil Dead offers more genuine suspense than probably half the other horror movies released in 1982 combined. In the undead versions of Linda and Cheryl, it has two of the most skin-crawlingly creepy fright-film villains of its era— villains who are all the more remarkable for retaining their menace even though they spend much of their screen time at least partially incapacitated (Linda by her ravaged ankle and Cheryl by the locked trapdoor to the cellar). There are a number of small touches in the script which contribute far more than their face value, as when Scotty, having just dismembered his girlfriend, announces that he and Ash are going to have to bury her, evidently because he is simply overwhelmed by shock and can think of nothing else to do to reassert control over the situation. Similarly, not even a truly slap-worthy delivery by Sarah York can spoil the chilling effect of Shelly’s out-of-left-field outburst regarding the zombified Cheryl after she has been safely corralled: “For God’s sake, what happened to her eyes?!?!” Finally, and most conspicuously, The Evil Dead is one of the few American horror films I’ve seen that can match the unnerving hallucinatory quality of their best Italian counterparts. Ash’s final face-off against the zombies is preceded by a long sequence in which reality seems to come apart at the seams, and for a while there, The Evil Dead feels almost like something Lucio Fulci would have made.

That latter point brings me, at last, to what has become The Evil Dead’s greatest claim to historical significance. As Sam Raimi’s first feature film, it marks the emergence of one of the major cinematic talents of the last 30 years. Raimi, despite long odds, has gradually developed into a filmmaker who can command massive budgets, and to whom big Hollywood studios will confidently entrust would-be blockbusters. He is a director with an instantly recognizable style, whom others further down the food chain— and not just gorehound fan-boys, either— rip off in an attempt to enhance their claims to legitimacy. And to a startling extent, most of the tricks and techniques for which he is now known can already be seen here in more or less mature (albeit obviously budget-constrained) form. The audaciously unlikely camera angles, the markedly eccentric editing, the willingness to combine seemingly incompatible approaches within the space of even a single scene, the unusually meticulous integration of visual and auditory elements— everything, in fact, but that damnable Three Stooges influence— is on display in The Evil Dead, leaving it a potent illustration of how boldness, imagination, and nearly insane commitment can triumph over lack of material resources. Right from the beginning, Raimi shows that he deserves all the breaks that came his way in later years.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal salute to the Video Nasties. Click the banner below to see just how much nastiness my colleagues and I could take.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact