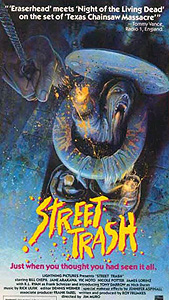

Street Trash (1987) -***

Street Trash (1987) -***

Given my dislike for Troma movies, I am no less surprised than anybody at how much I enjoyed J. Michael Muro’s Street Trash. A virtually plotless film that exists solely to assault the audience with its ever-escalating bad taste, Street Trash could very easily be mistaken for the work of Lloyd Kaufman and his followers, were it not for the much more accomplished special effects. It reveals a kindred fascination with gore so overblown and extreme that it becomes as goofy as it is gross. It leavens said gore with considerable amounts of sex, yet does so in a way that seems calculated to elicit the precise opposite of arousal. And it offers twice the misanthropy of even the most repellant Troma Team production, going so far as to play the carnal violation of a rape victim’s corpse for laughs. Yet somehow Street Trash appeals to me, for reasons that I’m not at all sure I can explain.

If nothing else, Street Trash is notable for focusing its story on a bunch of totally unromanticized hobos. They live semi-clandestinely in the auto junkyard owned by Frank Schnitzer (R. L. Ryan, from The Toxic Avenger and Class of Nuke ’Em High), where they are ruled over by a psychotic Vietnam vet named Bronson (Innocent Blood’s Vic Noto). As if this needed to be said, booze is nearly as valuable as money itself under hobo economics. Ed, the owner of the nearest liquor store (M. D’Jango Krunch), consequently sees more of Bronson’s bums than anybody, and his interaction with them is, on the whole, far from harmonious. Case in point: We receive our introduction to Ed and his establishment when a bum named Freddy (Mike Lackey) sneaks in behind Ed to burglarize the place while he opens up for the morning. Then, while running away from the enraged shopkeeper, Freddy encounters an older hobo named Wizzy (Bernard Perlman), from whom he steals what is, for him, a substantial amount of cash. Wizzy joins Ed in his pursuit of Freddy, with the chase causing several traffic accidents before Freddy is able to make good his escape. All in all, the second theft was not a very smart idea, though, for that money Wizzy was carrying was owed to Bronson for unspecified reasons, and now Bronson is going to have his eye out for Freddy.

Ed returns to his shop, where he has quite a bit of work to do. The basement is in only slightly less disarray than Bronson’s junkyard kingdom, and Ed figures it’s about time he did some straightening up. While he is thus occupied, Ed stumbles upon a sealed wooden crate in the crawlspace under the stairs; it proves to contain about half a gross of liquor in pint bottles. The labels identify the stuff as Viper, a brand Ed has never heard of in his life— which isn’t so surprising when you consider that the crate has probably been hidden away under the stairs since Prohibition. Figuring it’s good enough for the bums, Ed prices the Viper at a dollar a bottle and carries the crate upstairs.

Freddy is the first to buy a pint of Viper, but one of the other hobos pickpockets him before he has a chance to drink any of it. This is just as well for Freddy, really, because as soon as the other man takes a swig of his ill-gotten gains, he melts from the inside out, leaving little more than his right hand and an enormous puddle of Technicolor slime. Soon thereafter, a second bum has a Viper meltdown while relaxing on a fire escape. His messy demise attracts official attention, too, for his caustic renderings drip all over a passing yuppie (screenwriter Roy Frumkes), whose friends lead him straight to a nearby cluster of cops. Those policemen, led by a ’roid-raging detective named Bill (Bill Chepil), are busy just now investigating the murder of a motorist whose girlfriend says he was beaten to death by the boss of a homeless squeegie crew— she’s talking about Bronson, naturally. Bill initially takes the two melted-down hobos for more of Bronson’s victims, but he’s powerless to explain how their bodies could have wound up in such a condition. As the police medical examiner points out, not even napalm would do that to a man. Bill’s quest to bring Bronson to justice and solve the mystery of the melting bums is probably the closest thing Street Trash has to an actual story, but it gets shockingly little screen time and wraps itself up well before the end of the film.

Now let’s pick up what I would be tempted to call Street Trash’s biggest subplot, were there any legitimate main plot for it to be subordinate to. Schnitzer has a secretary named Wendy (Jane Arakawa), who with the boss’s extremely grudging permission runs a sort of informal social service for homeless teens out of his junkyard. Wendy’s favorite kid, Kevin (Mark Sferrazza), happens to be Freddy’s slightly less down-and-out little brother, and Wendy has fair enough reason to believe that she’s going to be able to salvage him. Kevin sort of has the hots for Wendy (the feeling is mutual— who knew dump funk had pheromone-like powers over the female sex drive?), but so, unfortunately, do both Schnitzer and Bronson. Bronson at least has a girl of his own (Nicole Potter) to keep him busy, but Schnitzer will spend pretty much the entire course of the movie pursuing an escalating campaign of sexual harassment against Wendy.

Then, finally, there’s Nick Duran (Tony Darrow). Duran is a high-rolling mobster, and he enters the story when his girlfriend (Miriam Zucker, of Thrilled to Death and Prime Evil) drinks herself into a stupor at Duran’s nightclub and wanders out back to puke up her guts. Freddy happens to see her, and since nothing says “keeper” like an expensively attired girl projectile vomiting in an alley, he takes her “home” to the junkyard. The other bums are quick to notice that Freddy has company, and once he passes out (leaving his “date” unsatisfied), they are even quicker to step in and finish the job. We don’t see this directly, but it is strongly implied that one of them bashes the girl’s head in with a pickaxe once they’re through gang-raping her. In any case, Duran’s girl is most assuredly dead when Schnitzer finds (and fucks) her the following morning. Bill ends up covering this case, too, and soon finds himself in the unexpected position of having to defend Freddy— whom Duran’s son or nephew or something (Frankenhooker’s James Lorinz) saw with the dead girl while he was working the door at the club— from one of the don’s assassins.

If you’re wondering how any of the aforementioned storylines— Bill’s pursuit of Bronson, Bronson’s pursuit of Freddy, Duran’s efforts to avenge his girlfriend, Wendy’s efforts to redeem Kevin, the matter of Ed and his crate of toxic hooch— might come together in the end, then I strongly suggest you stop it right now. The various threads begin as tangents, and they remain tangents until the closing credits. Storytelling is avowedly beside the point in Street Trash, which wants only to gross you out until you’re left with no alternative but to laugh or flee the building. Anecdotal evidence yielded by the crowd at B-Fest 2007 would seem to indicate that the incidence of the two possible effects is roughly 60-40 in favor of fleeing, even among an audience that has gone in expecting the worst, and I can’t say I’m surprised. It really does take a special kind of person to laugh at corpse-fucking and severed-penis keepaway (easily the most purely random set-piece in a movie that comes by much of its running time through random set-pieces), and I should probably be at least a little embarrassed to admit that I’m apparently part of this movie’s target audience. But shameful or not, I found Street Trash to be extremely funny, except during the dishearteningly long stretch in the middle where the movie gets bogged down trying to tell a story it doesn’t really have in the first place. But even that rather directionless section partially redeems itself with an honestly pretty disturbing flashback to Bronson’s ’Nam days. (The fact that Vic Noto really was a Vietnam veteran may have more than a little to do with the effectiveness of this scene.) I would have liked to see a little more focus generally, and in particular, I wanted the Viper to play a bigger role, but Street Trash still kept me entertained in a completely indefensible manner for the majority of its 91 minutes.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact