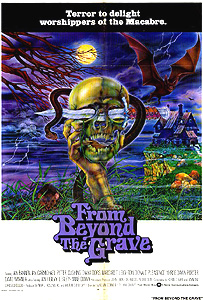

From Beyond the Grave / Tales from Beyond the Grave / Creatures from Beyond the Grave / The Creatures / The Undead / Tales from Beyond (1973/1975) ***

From Beyond the Grave / Tales from Beyond the Grave / Creatures from Beyond the Grave / The Creatures / The Undead / Tales from Beyond (1973/1975) ***

A lot of anthology horror movies derive some measure of unity from basing all of their stories on works by a single author. Usually, the author in question will be fairly well known: Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Robert Bloch, Richard Matheson, Stephen King, and so on. I was therefore taken somewhat aback when I reached the point in From Beyond the Grave’s opening credits where R. Chetwynd-Hayes was identified as the writer of all the source tales; I’d never heard of the guy. It turns out that Chetwynd-Hayes is a little like Dennis Wheatley— an enormously prolific writer and anthologist who was widely read and even somewhat respected in Britain, but relatively unknown on this side of the Atlantic. What’s weird, though, is that in 1973, when From Beyond the Grave was made, his success still lay mostly in the future, and he was almost as obscure at home as he remains in the US today. Amicus Productions creative boss Milton Subotsky just happened to pick up Chetwynd-Hayes’s short-story collection, The Unbidden, and decided that it would be the perfect starting point for the company’s next film. It was indeed a good choice. After the uneven and poorly received The Vault of Horror, From Beyond the Grave closed out Amicus’s eight-year cycle of portmanteau fright films on a high note.

The framing device is one of the studio’s best. Down an out-of-the-way alley somewhere in London sits an antique shop called Temptations Ltd. The proprietor (Peter Cushing) deals in pretty much everything under the sun— jewelry, furniture, knicknacks of all kinds, taxidermy animals, and who knows what else— but everything in the store is somehow accursed. How each customer fares in the face of the curse they bring home with their purchase is dependent upon their conduct in acquiring the malign merchandise. Something tells me we’re better off not knowing the fate of the one asshole (The Land that Time Forgot’s Ben Howard) who tries to rob the old man at gunpoint at the end.

First through the door is Edward Charlton (David Warner, from Grave Secrets and Tron). A serious collector of antiques, he is drawn to a centuries-old wall mirror, but balks at the £250 asking price. To be fair, that probably is a trifle steep for a piece in such condition, but Charlton’s counter-offer— £25— is just plain insulting. Nevertheless, the old dealer acquiesces to the 90% markdown, and Edward leaves with the ancient looking glass. At a party he throws that night, one of the guests remarks that Edward’s new acquisition looks like something a medium would own, which inspires one of the others to suggest a séance. This being 1973, everybody is up for a little paranormal mucking about, but things get a tad creepier than any of them actually wanted. Edward, leading the séance, has a vision of a very large man in a black cloak (Arabian Adventure’s Marcel Steiner), with his hair and beard done up in a non-specifically obsolete style; the caped man runs Charlton through with a rapier, at which point the group’s collective trance is broken. Naturally Edward is unharmed once the phantasm fades away, and no one ascribes the evening’s adventure much significance. Later that night, though, a spectral and cadaverous version of the man from Edward’s vision appears to him in the mirror, and commands him to kill. Edward refuses, of course, but the spirit in the mirror has the power to inflict psychic tortures fit to drive just about anyone to do just about anything. Within days, Charlton has become a post-Swinging London Jack the Ripper, while the mirror entity grows stronger with each life Edward takes…

The next Temptations Ltd. customer is the aptly named Christopher Lowe (Ian Bannen, of Doomwatch and Watcher in the Woods), a hen-pecked loser clinging with increasingly unrealistic tenacity to a past in which he still appeared to have a future. Lowe’s wife, once a sensuous, spirited beauty, has aged into a doughy harridan who treats him with undisguised contempt. (In an impressively canny bit of casting, Mabel Lowe is played by former hot chick Diana Dors, from Berserk and Nothing But the Night.) His son, Stephen (John O’Farrell), is just as disrespectful, so that the only thing Christopher dreads more than going in to his unrewarding job every morning is coming home from it at the end of each day. It’s enough to make Lowe nostalgic for the army! Not that his military career was in any way distinguished, but at least there a man knew where he stood, and could reasonably count upon getting his due.

That sentiment, apparently, is what leads Lowe to buy a pair of shoelaces from a pensioned-off serviceman street peddler (Donald Pleasence, of Wake in Fright and Warrior Queen) one fateful afternoon. But it’s the peddler’s appreciation of his generosity— the first genuine, unfeigned appreciation Lowe has experienced in who knows how long— that leads him to start adding ever-longer delays to his walk home, taking time out to chat with the older man. Mind you, even these pleasant interactions have their negative side, for Lowe is very self-conscious about never having served on the front lines or faced any serious danger during his years under arms. So when he walks by that antique shop, and notices a Distinguished Service Order on display in the window, he gets to thinking about inventing a more satisfactory biography to accompany his talks with the peddler— or Jim Underwood, to give him his proper name. One slight problem, though. Evidently Lowe isn’t the first self-aggrandizing douchebag to devise such a scheme, because the shopkeeper won’t sell the medal to anyone who can’t produce the certificate verifying that they or someone related to them are entitled to wear it. Still, the fantasy of engaging with Underwood not merely as an equal, but as someone meriting respect and even deference is enormously attractive. In the end, Lowe shoplifts the coveted medal, showing it off to his new friend at the earliest opportunity.

The relationship between Lowe and Underwood takes a second crucial turn when the latter invites the former over to visit. It isn’t just that hanging out with Jim at home means concocting a cover story to explain why he’ll be missing supper with his own family on an increasingly regular basis, although Mabel’s prying is certainly a consideration. The real issue is that Underwood has a daughter (Pleasence’s real-life progeny, Angela, who can also be seen in Symptoms and The Godsend). Emily is quite taken with Christopher, and she discerns at once the unhappy state of his marriage. The girl makes it her project to offer Lowe an alternative, in more ways than the ones that spring readily to mind. Emily Underwood is a witch, so if Christopher would like to be rid of Mabel, he’s got a pretty wide range of options…

Next comes Reginald Warren (Ghost Ship’s Ian Carmichael), whose approach to screwing over the owner of Temptations Ltd. splits the difference between Charlton’s and Lowe’s. Warren sees a silver snuff box that he fancies in one of the display cases, but he doesn’t fancy it enough to pay £40 for it. There’s another, cheaper box beside it, however, so Reginald switches the two price tags while the proprietor isn’t looking. On the train home, Warren finds himself sharing a compartment with an annoying old lady who calls herself Madame Orloff (Margaret Layton, of Frankenstein: The True Story and Journey Through the Black Sun). The Awful Madame Orloff claims to be a psychic medium, but more importantly, she also claims that Warren has an elemental on his shoulder. A right nasty one it is, too— one of the very rare homicidal variety. (“I’ve seen them sex-starved and alcoholic, but I’ve never seen a killer before,” the supposed medium muses.) Naturally, Reginald dismisses her as a loony, and accepts her business card only in the hope that doing so will shut her up. He starts to see things differently after he gets home, however. First the dog refuses his company, barking and snarling at him as if he were a hostile stranger (or had one perched on his shoulder, if you’d prefer). Then his wife (The House that Dripped Blood’s Nyree Dawn Porter) accuses him of slapping her from behind when he not only never touched her, but was standing too far away to do so even if he’d wanted to. And while he and Susan are sleeping that night, something seizes her by the throat as if trying to choke the life out of her. Good thing Reginald didn’t throw away Madame Orloff’s card like he meant to…

Finally, William Seaton (Ian Ogilvy, from Death Becomes Her and The Sorcerers) makes a remarkable discovery amid the junk at the antique shop. Propped up against one of the walls is an intricately carved hardwood door that perfectly suits his eccentric and rather morbid taste in home décor. The shopkeeper avers that it was removed from a derelict castle, where it once opened onto a parlor decorated all in blue, and offers to part with it for a remarkably thrifty £50. William has but £40 in his wallet just now, but the antique dealer decides that’ll do. The minimal haggling plus Seaton’s honesty in not raiding the cash register when the proprietor gives him the perfect chance will stand William and his wife, Rosemary (Leslie Anne Down, of Countess Dracula and In the Devil’s Garden) in good stead once the door’s curse reveals itself. When the hour is right, the weird artifact serves as a portal to the pocket universe created by the warlock Sir Michael Sinclair (Jack Watson, from Horror on Snape Island and Konga). There, in a magically preserved version of the blue room in his old castle, Sinclair dwells in diabolical immortality, sustained by periodic infusions of human blood. He’s just about due for a refill now, too…

Like the first film in the Amicus horror anthology cycle, Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors, From Beyond the Grave is noteworthy for the consistent quality of its several segments. It is possible to rank them, certainly, but the distance separating the strongest from the weakest is not great. My favorite of the lot is Christopher Lowe’s story. As the amount of space I granted it above should suggest, it’s the most complex and fully developed. Indeed, it might almost have supported a feature-length treatment. The psychological acuity of the bond between Lowe and Underwood greatly exceeds what one usually finds in anthology films, and Ian Bannen and Donald Pleasence are both wonderful as pathetic men who find in each other reassuring echoes of the days in which they weren’t pathetic yet. Angela Pleasence is impressive, too, creepy and appealing at the same time, although she gets a leg up simply because of how disconcerting it is to see so exact a duplicate of her father’s face on a young woman. Again the casting plays perfectly to the psychology of the script, for while Pleasence is not physically attractive in any normal sense, she conveys a warmth and docility that a man in Lowe’s position would obviously find difficult to resist. The flipside, of course, is Diana Dors as Mabel, all contemptuous stridency and angry regret. Dors is the one who really surprised me. The movies I’d seen her in previously treated her essentially as a British Mamie Van Doren— big hair and bigger tits without much going on behind them. Mabel, however, is a role worth throwing oneself into, and that’s just what Dors does. Crucially, she and director Kevin Connor alike seem determined to keep Mabel from being totally unsympathetic. After all, she clearly didn’t want this squalid life for herself any more than Christopher did. I should probably also mention that this segment has a terrific twist ending, but it’s one that I like way too much to say any more about it.

The other three segments— and the framing story, for that matter— are more or less equal. Charlton’s vignette is the most gruesome, and easily the bleakest. It also builds up a nice charge of tension in the endgame, as Edward’s downstairs neighbor (Tommy Godfrey, from The Vault of Horror and Straight on Till Morning) and closest friend (Wendy Allnutt) inadvertently put themselves into competition to become the victim whose blood will finally satisfy the thing in the mirror. On the downside, the nature of the mirror entity’s hold over Charlton is never as clear as it should be, nor does Edward put up enough fight against it for the full horror of his position as unwilling serial killer to come across.

The final segment, with Sir Michael Sinclair’s door, could almost be a remake of the first. Sinclair needs exactly the same thing as the guy in Charlton’s mirror, just not as much of it. That hurts the movie a little, but the similarity also plays off in the framing story with the revelation that Seaton, unlike Charlton, dealt squarely with the Temptations Ltd. proprietor. That is, we’ve already seen how this scenario could have played out, so it changes our impression of the shopkeeper when we learn that honesty toward him serves as protection against the worst of the curses on his goods. In retrospect, he seems less like a demonic figure sowing chaos than a trickster spirit running a sting operation against liars and cheats. There’s also something to be said for the visual impact of the Bava-esque set for Sinclair’s lair, and for having at least one story in which the central character isn’t kind of a jerk.

In between, the tale of the elemental sticks out somewhat for its tonal mismatch with the other segments. The Amicus anthologies had delved into black comedy before, of course (indeed, some commentators attribute The Vault of Horror’s commercial failure to too much of such delving), but I don’t recall them ever straying this far into outright camp without becoming insufferable. The “funny” bits that worked were usually closer to the grim absurdity of the vine segment in Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and Joan Collins’s battle with a homicidal Santa Claus in Tales from the Crypt. The broader approach works here, I think, for the same reason as it does in the best moments of The Smiling Ghost; goony old Madame Orloff may be played for laughs, but the threat posed by the elemental is unmistakably real and serious.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact