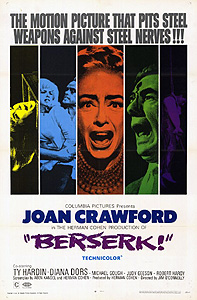

Berserk (1967) **½

Berserk (1967) **½

After Robert Aldrich brought their careers back to life with Whatever Happened to Baby Jane?, Bette Davis and Joan Crawford alike spent a lot of their time inflating the budgets of what would otherwise have been extremely cheap horror films. For Crawford, that meant teaming up successively with two independent producers who first drew attention to themselves toward the end of the previous decade. First came William Castle, who used her residual fame to help wean him away from dependence on loopy promotional gimmicks. Then it was Herman Cohen’s turn. Cohen’s name isn’t nearly as widely remembered as Castle’s, but it probably ought to be, since he was the mastermind behind American International Pictures’ late-50’s teen-monster cycle. Afterwards, he became AIP’s man on the ground in Great Britain, presiding over movies like The Headless Ghost and Konga. Cohen was still operating in the Isles when he got his hands on Crawford, casting her in Berserk, his bid to get in on the on-again, off-again 1960’s vogue for circus-themed horror flicks.

It’s been a difficult season for the Rivers Circus, and when the show’s star performer, a tightrope walker named Gaspar (Thomas Cimarro), falls to his death in a freak accident right in the middle of his act, co-owner and business manager Albert Dorando (Michael Gough, from Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors and The Skull) is just about ready to hang it up for the year. In fact, Dorando would just as soon sell out his interest in the circus to his longtime partner, Monica Rivers (Crawford), from whose family the circus takes its name. Monica, however, does not care for that plan, partly because she lacks the cash on hand to buy Dorando out, but also because she considers his defeatist attitude to be premature. In fact, she is convinced that Gaspar’s grisly fate actually heralds a major turnaround in the circus’s fortunes. Reasoning from the well-established morbidity of the paying public, she predicts (correctly, as it turns out) that tomorrow’s show will have the biggest turnout of the tour so far, and with that in mind, she puts Dorando to work bothering all the agents in his rolodex in order to find some exciting new act to put on in Gaspar’s place.

As it happens, none of Dorando’s contacts come through in a manner satisfactory to Monica, but a freelancer from America wanders in on his own initiative with an offer no circus proprietor could turn down. First off, he’s willing to let Monica set her own price if she likes his act. And secondly, Frank Hawkins (Ty Hardin, of The Space Children and I Married a Monster from Outer Space), like the deceased Gaspar, performs on the highwire, and he’s got an angle even Monica has never encountered before. Not only does Hawkins do his act without a net, he does it blindfolded, above a carpet of bayonets! Now that is what I call showmanship. The American says he came to last night’s show, and that he reasonably concluded on the basis of what he saw that the Rivers Circus could maybe use somebody with his talents. You’ve got to wonder, though— isn’t it awfully convenient that there was a highwire guy in the audience on the very night that Gaspar took his fatal plunge? Hawkins starts to look even more suspicious a short while later, when one of those agents Dorando summoned accosts him outside the big top and attempts to blackmail him into a business relationship by dropping hints about something that happened in Canada several years ago. All that agent gains from the attempt is a sound thrashing, however, and the only contract Hawkins signs is handed to him by Dorando.

With its new tightrope walker onboard, the Rivers Circus departs from Leeds, bound for Liverpool, but in all respects save the financial, Monica and company bring their troubles right along with them. To begin with, Monica strikes up an affair with Frank Hawkins. Now under most circumstances, my sole response to this development would be, “Go, Monica! You ride that young-enough-to-be-your-kid stallion for all he’s worth, you lusty, fishnet-wearing granny, you!” but these particular circumstances are fraught with ominous potential. Frank wants a Relationship, whereas Monica just wants to fuck. Meanwhile, Dorando’s had an affair of his own with Monica going for seven years, and he doesn’t take kindly to being booted out of her bed in favor of some young upstart. So when somebody murders Dorando shortly after Monica and Frank have a fierce argument on the subject of what exactly the two men mean to her, it’s only to be expected that people would get suspicious— even the ones who don’t see Monica stealing the partnership contract out of Dorando’s office caravan to burn it in her trash can immediately after the slaying. And by “people,” I mean practically everybody who works for the Rivers Circus, to say nothing of Scotland Yard. Laszlo the magician (Philip Madoc, of Daleks: Invasion Earth 2150 A.D. and Dr. Jekyll & Sister Hyde) is the first to make the connection between the two recent deaths, noting how much Monica stands to gain first from the spike in business that followed Gaspar’s fall and second from the sudden streamlining of her romantic situation. Bruno the dwarf (George Clayton, from Twins of Evil and The Devil Within Her) remains unshakable in his loyalty to the boss, but the other sideshow performers aren’t so sure, and Laszlo’s assistant/girlfriend, Mathilda (Diana Dors, from Theater of Blood and The Amorous Milkman), is utterly convinced that Monica is a killer. What’s more, she’s prepared to say so even when Monica is around to hear it.

As for Scotland Yard, they enter the picture when Commissioner Dalby (Geoffrey Keene, from Horrors of the Black Museum and Taste the Blood of Dracula) sends Superintendent Brooks (Robert Hardy, of Psychomania and Demons of the Mind) around to investigate Dorando’s murder, and to reopen the issue of Gaspar’s supposed accident. Brooks questions everybody— Mathilda most definitely included— and both Frank and Monica tell him a number of very interesting lies when their turns come around. Frank claims not to have known about Gaspar’s death at the time when he applied for a job with the circus, and Monica denies not only her affair with Dorando, but the dead man’s co-ownership of the circus as well. What’s more, Monica and Frank catch each other in their deceptions, and Frank starts trying to lever Monica into cutting him in as a partner, much as Dorando had been. Interestingly enough, however, he pursues his blackmail with the same soft sell as he had his employment bid, leaving it to Monica to decide just how much of a stake in the circus he’ll receive and when. The stakes for Monica, meanwhile, are getting higher by the moment. First, her teenage daughter, Angela (Judy Geeson, from Doomwatch and Inseminoid), turns up unbidden on the doorstep. Finally fed up with the long separations from her mother that have characterized her whole life, Angela has contrived to get herself expelled from boarding school, on terms that leave Monica with little choice but to take her on in some capacity at the circus, murder investigation or no. Then somebody tampers with Laszlo’s sawing-a-woman-in-half equipment so that Mathilda gets bisected for real. With Brooks now keeping a nearly panoptic watch on the Rivers Circus and Angela taking over for the hopelessly besotted assistant to Gustavo the knife-thrower (Peter Burton, from The Doctor and the Devils and The Love Box), it seems a fairly safe bet that the tour’s climactic London engagement will serve as the climax to the mysterious killing spree as well.

Berserk is a fun movie, but in the end, it isn’t a whole lot more than that. There’s too much emphasis on the circus performers and their acts, for one thing, and too little on the murders that we’re really here to see. Every acrobat and animal trainer who steps into the ring gets the camera’s undivided attention for the duration of their performance, and while that’s fine in the opening third of the film, it has the effect of stopping the movie dead every time once the killings begin in earnest. The relationship between Monica and Frank also loses most of its credibility once it finally develops from a matter of mutual exploitation into a genuine romance— and that’s only partly because of the twenty-year age gap separating them. The filmmakers are to be commended for attempting to get around the age issue by making a plot point of it (even if they do so rather belatedly and with notably imperfect success), and in any event, Joan Crawford still looked good enough at the age of 61 to get away with spending most of the movie wearing a form-fitting scarlet tuxedo jacket and a pair of fishnet tights. No, the real problem with the relationship in its terminal phase is that it seems totally out of character for both participants, each of whom has hitherto shown nothing but a ruthless maneuvering for advantage in all of their dealings with other people. For Frank and Monica to fall in love at all— let alone with each other— would seem to require a major personal transformation, and none is forthcoming. Nor does either character seem sufficiently appealing to constitute a transformative influence in and of themselves. Brooks’s investigation comes across as lackadaisical in the extreme, and the climax has a decidedly uneven impact. On the one hand, it wins some of my affection for killing off a character who seems completely off-limits by that point, but on the other, it contains a just-for-the-hell-of-it surprise that pins the murders on someone who hasn’t played nearly a big enough role to earn, so to speak, such distinction. It’s that above everything else, I think, that led me to the one really thought-provoking aspect of this movie. It left me thinking that Berserk suggests what the gialli might have been like had they been invented by Brits instead of Italians. All the elements are here— the impractically showy body-count murders, the dithering cops, the conniving women, the unresolved red herrings, the ridiculous denouement— but there’s a primness about the proceedings that could not be farther removed from the obsessively orchestrated mayhem of Mario Bava, Dario Argento, or their numerous down-market competitors. Instead, Berserk is more a Horrors of the Black Museum-style charismatic maniac film, only without the charismatic maniac.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact