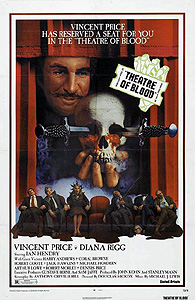

Theater of Blood/Theatre of Blood/Much Ado About Murder (1973) ****

Theater of Blood/Theatre of Blood/Much Ado About Murder (1973) ****

My longtime readers may remember how displeased I was with Dr. Phibes Rises Again. Luckily, there is another movie to which people may turn when they want more of the diabolical Anton Phibes— it just isn’t actually a Phibes movie, nor indeed was it released by American International. It does, however, have Vincent Price as an eccentrically evil genius who is generally believed to be dead, waging a bizarre and thematically unified campaign of vengeance upon eight men and one woman against whom he nurses a years-old grudge, and it spiffies up the place with an actress at least as easy on the eyes as The Abominable Dr. Phibes’s Virginia North. But instead of a composer, theologian, and inventor, Theater of Blood’s charismatic maniac is an actor who believes himself unjustly maligned as a ham, who slays the critics who denied him a coveted award by methods drawn from the plays of William Shakespeare. In other words, it was the most perfect imaginable premise for a Vincent Price movie, and it’s no wonder that Price himself reportedly regarded it as his favorite among the films in which he appeared.

London theater critic George Maxwell (Michael Hordern, from The Bed Sitting Room and Demons of the Mind) is having breakfast with his wife when the telephone rings. There’s a police constable on the other end, alerting Maxwell that an abandoned building which he recently purchased as a development investment has been taken over by squatters, and that his presence will be necessary if they’re to be rousted in a legal manner. Maxwell grumbles a bit, as this will likely make him late for the afternoon’s meeting of the Critics’ Circle, but he agrees to meet the policeman and his partner in front of the property. The bums inside prove to be a stubborn, truculent bunch, and the two cops strangely don’t seem to be very interested in backing Maxwell up. There’s an excellent reason for this, in that the policeman in charge is really Edward Sinclair Lionheart (Price), a Shakespearean actor who was supposed to have perished three years ago, and the half-mad bums in Maxwell’s building are his private army. The squatters savage Maxwell while Lionheart looks on approvingly, and then the actor himself finishes his victim off with a knife in the back, reciting dialogue from the assassination scene of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar in a steady stream. It is surely no coincidence that Lionheart and his minions have chosen the Ides of March as the date for Maxwell’s murder.

The other eight members of the Critics’ Circle have just gotten sick of waiting for Maxwell’s arrival when one of their secretaries bustles in to break the bad news a few hours later. Peregrine Devlin (Ian Hendry, of Captain Kronos, Vampire Hunter and Journey to the Far Side of the Sun), the Critics’ Circle’s unofficial leader, goes to meet with Inspector Boot (Milo O’Shea, from Barbarella and It’s Not the Size that Counts) at the scene of the crime, and it is he who first notices what will turn out to be an extremely important clue. Pasted to the wall above the spot where Maxwell died is a poster advertising an Edward Lionheart production of Julius Caesar, dating from the year of his supposed death.

Elsewhere, Hector Snipe (Dennis Price, of Devil’s Island Lovers and Vampyros Lesbos), another member of the Critics’ Circle, has received insider information to the effect that Lionheart is both alive and planning a high-profile comeback. Offered an exclusive interview, he goes to the long-abandoned theater which Lionheart apparently intends to renovate as part of his return to the stage, arriving during what the actor describes as a rehearsal. Specifically, he says it’s a rehearsal of the scene from Troilus and Cressida in which Hector is fatally ambushed by people whom he took to be his friends. This, I emphasize, comes just moments after Lionheart’s stage manager assures Hector Snipe that he is “among friends here.” Two down, seven to go.

Some time later, on what I take to be that very night, Lionheart arranges to have himself and an accomplice smuggled into the home of Horace Sprout (Arthur Line, from No Sex, Please— We’re British and The Bawdy Adventures of Tom Jones) within an antique steamer trunk. Lionheart anesthetizes both Sprout and his wife as soon as they’ve gone to sleep, and then saws off the man’s head. That head turns up on Peregrin Devlin’s property the following morning, leading him to place an immediate call to Inspector Boot. Then, at George Maxwell’s funeral, the morose scene is interrupted when a horse comes galloping toward the assembled mourners, dragging the badly worn corpse of Hector Snipe behind it. (Remember that after Hector was dead, Achilles made several circuits around the walls of Troy, dragging the body behind his chariot.) Again, Devlin is reminded of Edward Lionheart, for at just that moment, he spies the actor’s daughter, Edwina (Diana Rigg, who unfortunately has not brought any of her old “Avengers” wardrobe with her for this project), paying a visit to her old man’s cenotaph. In any case, it’s plain enough by now that somebody has it in for the Critics’ Circle, and Inspector Boot wants the lot of them rounded up, apprised of the situation, and put under police protection. Boot doesn’t move fast enough to save Trevor Dickman (Harry Andrews, from I Want What I Want and Horrors of Burke and Hare), however, for the latter man has already allowed himself to be charmed by a pretty, young actress into coming to see her amateur troupe’s rehearsal of The Merchant of Venice. Theirs is a rather free, modernistic interpretation, and in it, Shylock gets his pound of flesh.

It is at the group meeting with Boot that Devlin shares his growing suspicion that the maniac targeting the Critics’ Circle may be the supposedly deceased Edward Lionheart. Devlin has in his possession a handbill from Lionheart’s final performing season, and he points out to Boot the similarities between the circumstances of Maxwell’s, Snipe’s, and Sprout’s demises and those of the key death-scenes in the first three plays on Lionheart’s last schedule: Julius Caesar, Troilus and Cressida, and Cymbeline. Devlin also explains that Lionheart would have motive aplenty were he somehow still alive, for it was the Critics’ Circle’s decision three years ago to give their prestigious annual award to an up-and-coming actor, rather than to him, that sparked what was believed at the time to be Lionheart’s suicide. A hell of an exit it was, too, as the jilted actor threw himself into the Thames from the balcony of the Critics’ Circle’s penthouse office after barging in and demanding the award which he believed was rightfully his. No sooner has Devlin finished relating the foregoing than a courier arrives, bearing a box containing a pound of cardiac muscle cut from Trevor Dickman’s chest, together with a note ostensibly from Dickman, assuring his living colleagues that although he regrettably cannot be present, his heart is with them all. That clinches it, so far as Devlin is concerned: “It’s Lionheart, alright. Only he would have the temerity to rewrite Shakespeare.”

Boot is not convinced, however, and when Oliver Larding (Robert Coote, from The House of Fear and The Thirteenth Chair) is drowned in a barrel at a phony wine-tasting orchestrated by Lionheart and his followers, the inspector has Edwina arrested. It’s difficult to argue with his reasoning (“When I have two suspects, and one of them is alive while the other isn’t, which one do you think I’m going to arrest?”), but the diversion leaves Devlin open to attack in a manner derived from Romeo and Juliet’s big sword-fighting scene. Lionheart is merely toying with Devlin for now, however, tipping his hand so that his victims will know for certain whom it is they have to fear. (This curious feint also provides a chance for some exposition, revealing— somewhat to the movie’s detriment— how Lionheart survived his plunge from the balcony and fell in with the motley band of bums who now assist him.) From here on, Devlin will attempt to persuade Edwina that it is her humanitarian duty to aid in capturing her father, while Boot tries (with about as much success as attended the efforts of the Scotland Yard men in The Abominable Dr. Phibes) to protect the remaining members of the steadily contracting Critics’ Circle from Lionheart’s depredations. Solomon Psaltry (Jack Hawkins, from Tales that Witness Madness and the first talkie version of The Lodger), Chloe Moon (Dr. Crippen’s Coral Browne), and Meredith Merridew (Robert Morley, of A Study in Terror and The Old Dark House) are all doomed, their fates drawn from Othello, Henry VI, Part 1, and Titus Andronicus, respectively, and Lionheart has some especially nasty King Lear action planned for Devlin as the endgame. There’s also a sly little twist in the climax, at which point Theater of Blood finally parts company to some extent with the Phibes model.

I don’t think it’s much of an exaggeration to say that Theater of Blood stands as the culmination of Vincent Price’s entire career. Not only is it the most infectiously entertaining movie he’d made since The House on Haunted Hill, it manages to pull together all the major currents of his horror films since the late 1930’s in a way that both pokes fun at and pays tribute to its star. Most obvious, of course, is the premise itself, the revenge of a much-loved ham actor against the critics who have done nothing but belittle him, often unfairly. Though this is not explicitly stated, it is strongly implied that Lionheart’s plays were big moneymakers, wildly popular with working- and lower-middle-class audiences who came to them precisely because of the appeal of their blood-and-thunder take on the classics, a description which applies equally well to all the countless times when Price headed up a garish adaptation of something by Edgar Allan Poe, Jules Verne, Nathaniel Hawthorne— or indeed William Shakespeare. The Price-Shakespeare connection is made in an especially clever way with the murder of Oliver Larding, for Price had already played out that very scene on film twice before: first as the victim in Universal’s 1939 Tower of London, then again as the perpetrator in the 1962 version directed by Roger Corman. This movie’s recapitulation of Richard III’s wine-vat drowning becomes doubly appropriate when one remembers that the earlier Tower of London marked Price’s very first foray into the genre that would define his career almost completely in the aftermath of House of Wax.

But perhaps the more important parallel between Edward Lionheart and the man portraying him lies in Lionheart’s aggrieved conviction that he has been consistently underrated by the taste-makers of the press. Lionheart, of course, considers himself to be a fine actor; Edwina repeatedly describes him as “the greatest actor who ever lived;” and certainly all the punters who filled up theaters to see his plays must have seen at least some merit in him. But to critics like Devlin and his circle, Lionheart was nothing but an overstuffed blowhard with delusions of grandeur. Again, it would be easy to say something similar about Price, who more often than not overplayed his roles in a way that has rarely been seen since his gradual withdrawal into a comfortable semi-retirement in the 1980’s. What is easy to miss— and what I confess I missed myself for a number of years— is that Price overacted not because that was all he could do, but because that was what he usually believed his parts required. When he thought something more subtle was called for— as in The Conqueror Worm or The Fly— Price could and did rein in the hamming for which he was so justly famous. More than any other single film, Theater of Blood demonstrates the mostly unused breadth of Price’s range as an actor. True, Edward Lionheart is very much the usual Vincent Price madman (hell, he’s practically the quintessence of the type!), but because his various schemes to trap his enemies frequently require him to disguise himself as somebody else, we get to see Price trying his hand at roles most of his fans would never have imagined for him. You want to see Price play an English bobby? A smarmy French masseur? A comical chef? How about a queer 70’s hairdresser? Well, Theater of Blood has all of those. The hairdresser was the one that really stunned me, because Price really does sell it, even the part about posing as a man half his age. We are also made privy, as is only appropriate, to any number of Shakespeare recitations, and while many of them are bizarrely tone-deaf, those that aren’t unmistakably reveal the rest to be a deliberate stylistic choice on the part of Price and/or director Douglas Hickox, a case of Price playing the part of a crummy actor.

Finally (although this may well be a fortuitous accident), Theater of Blood plays as though its creators understood that the curtain was descending on horror movies of this type, and that some sort of grand final bow was in order. Admittedly, the paradigm-altering release of The Exorcist was still months in the future, but surely the writing was on the wall for all to see during the first quarter of 1973, when Theater of Blood was in production. The preceding five years had already witnessed Night of the Living Dead, Deliverance, The Last House on the Left, the early gialli of Dario Argento and the late ones of Mario Bava, the mature (if we can call it that) works of Hershell Gordon Lewis, and who knows how many other relatively well-exposed horror films of an exceedingly gritty and aggressive nature, and even television had started weighing in with the likes of Duel. The venerable mad genius could hardly have looked more antiquated, and the true brilliance of Theater of Blood may lie in its implicit acknowledgement of its own obsolescence. The way Price delivers the soliloquy from King Lear in his death scene, it feels strangely like a eulogy not just for Lionheart’s incomplete revenge, but for Price’s own career and indeed for the whole rapidly waning school of horror movies that had made him a star. All things considered, Theater of Blood comes across as one of the most thoughtfully self-aware fright films of its, or any other, era.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact