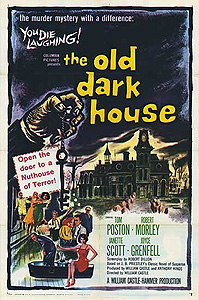

The Old Dark House (1963/1966) -*

The Old Dark House (1963/1966) -*

I wish I knew what James Carreras and Anthony Hinds were thinking in 1962, when they decided to bring William Castle over from America to produce and direct their remake of James Whaleís The Old Dark House. Everything Iíve read about the studioís history devotes as little attention as possible to The Old Dark House, and I can totally understand that. Itís a dreadful, shameful movie, a humiliating blot on two otherwise remarkably consistent records. But you know there has to be a story here, and Iíd love to hear it. Hammer, after all, was not in the habit of handing creative control of their products over to people from outside their usual stable of producers, directors, and writers. Theyíd imported plenty of American talent over the years, but only for jobs in front of the camera. The Hammer regulars had very carefullly developed an instantly recognizable house style since the studioís rise to international prominence in 1957, and if itís true what they say about imitation, then that style was among the most sincerely flattered all over the horror-film-producing world. Castle, too, had an unmistakable style, and it could not possibly have been any further at variance from Hammerís. Although luridness was surely a core Hammer characteristic, filmmakers like Terence Fisher, Freddie Francis, Val Guest, and Jimmy Sangster almost always managed to make it look classy and well-mannered. Castleís luridness was of an unapologetically boorish and thoroughly American stripe. Having him over to make a Hammer film was like hiring a carnival barker to sell Jaguars. All I can think of to explain it is the fact that The Old Dark House was a co-production with Hammerís latest transatlantic partners, Columbia Pictures; Castle was arguably Columbiaís star horror director in the early 60ís, and I can imagine that studioís leadership snowballing Hinds and Carreras with some bunch of bullshit about creative synergy or whatever. What this most unlikely of alliances produced, however, was something close to the exact opposite of synergy. Castle and Hammer turn out to be the two great tastes that induce gagging and nausea together.

Tom Penderel (Tom Poston, of Zotz!) is an American car salesman living in London. Specifically, he seems to work at a Lincoln dealership, which I didnít know they had over there. His living arrangements are rather peculiar, for although he shares his flat with another man, Penderel and Casper Femm (Peter Bull, from The 3 Worlds of Gulliver and Footsteps in the Fog) have never actually met. This is possible because Casper occupies the flat only during the day while Tom is at work, vacating it each evening to goÖ well, somewhere. The two sort-of roommates are about to make each otherís acquaintance at last, however, for Casper has lately gotten it into his head to buy one of Tomís extravagantly huge and powerful vehicles. To that end, Tom leaves the lot at quitting time in a powder-blue Continental convertible, and drives it to the private club where Casper does his gambling. Penderel has a hard time talking his way past the concierge (whose whole job, after all, is to keep the club free of rabble like Tom), but eventually gets in with a stern warning not to take part in any of the games. The meeting does not go quite as Tom expects. Casper is enchanted with the car, alright, but he wants Penderel to drive it home for him. And by ďhome,Ē Casper means not the apartment that he and Tom share, but rather the ancestral manse of the Femm family, far away in Dartmoor. That, apparently, is where he disappears to every night. Tom will have to make the drive alone, too, because pressing time constraints about which Casper feels himself not at liberty to speak here demand that he himself return by airplane. Penderel understandably balks at this onerous stipulation, but Casper wins him over partly by appealing to a wildly exaggerated conception of their friendship and partly by mentioning his lovely cousin, Cecily.

The drive to Dartmoor is uneventful until Tom comes to the end of it. An intense, persistent thunderstorm breaks out during the home stretch of the journey, Femm Manor turns out to be accessible only via a winding dirt track through the center of an immense marsh, and the front gate is stuck shut when Penderel finally arrives before it. His efforts to unstick the gate have the collateral effect of dislodging the enormous granite gargoyle atop one of the masonry columns anchoring it, and while Tom dodges the falling statue handily enough, Casperís Lincoln isnít so fortunate. Also, the knocker on Femm Manorís front door was booby-trapped by Casperís Uncle Potiphar (Mervyn Johns, from Dead of Night and The Confessional) so as to dump anyone who tries to use it through a trapdoor into the cellar, where he can safely interrogate them about their business at the house. Ohó and Casperís dead, too.

Waitó what?! Yes, Casper is dead, and although none of his relatives profess to know how, they are virtually unanimous in suspecting foul play. Tom gets the latter information (or at least some hints in its direction) from Cecily (Janette Scott, from Paranoiac and The Day of the Triffids)ó who, incidentally, pretty well lives up to her billing and marks herself out thereby as Penderelís natural love-interest. The prime suspect appears to be Cecilyís father, Roderick (Robert Morley, of A Study in Terror and Theater of Blood), de facto head of the Femm clan, and she makes every effort to hustle Tom out the door before her old man returns home. No such luck there. Roderickís arrival is not without its upside, however, for it means that at last thereís someone able and willing to answer a few of the 11,000 questions that Tom has formulated since being dragooned into delivering Casperís car to the chateau.

To begin at the beginning, the Femm family is obviously very rich, but that wealth was not gained legitimately. The founder of the line was a notorious pirate called Morganó whom we are indeed apparently supposed to identify with that Captain Morgan, even though the timeline and biography for the Femmsí Morgan donít remotely line up with his. Building this house in the middle of a swamp was Morganís way of going belatedly straight, and the terms of the trust in which he put his plundered riches were intended to keep all of his descendants out of the buccaneering business, too. In order to maintain any claim to a share of the family fortune, a Femm must meet at least a minimal standard of permanent residence within the old manse; they must be present beneath its roof each midnight, which is obviously incompatible with a life of piracy on the high seas. That it would also be incompatible with many other totally legitimate lifestyles was apparently of no concern to Morgan. The trust is inalterable so long as the house remains within the family, which is the next best thing to saying itís inalterable forever, since thereís also a clause forbidding its sale. Not even arson would get the clan out from under their ancestorís thumb, since the only fire that could harm the fortress-like walls of Femm Manor is the volcanic variety from which the basalt blocks originally sprang. Meanwhile, the funds disbursed from the trust as an allowance to the heirs are equally divided among all of them who play by its rules, so that they each have an obvious incentive to engineer each otherís disinheritance.

That last is why Casperís death has everyone so worried. Itís hard to think of a more efficient means of engineering someoneís disinheritance than murdering them, and sanity is unmistakably in short supply among the Femms. To all outward appearances, the younger generationó Casper and his twin brother, Jasper (also Peter Bull); Cecily; the predatorily amorous Morgana (Carry On Screamingís Fenella Fielding)ó are merely eccentric, but their elders to a one are loonier than Harley Quinn. Potiphar is expecting the end of the world any day now, and has an ark built and stocked to Biblical specifications in the backyard, all ready for the rains to float it. (The funniest scene in the movieó funny for all the wrong reasonsó concerns a meeting between Penderel and one of Potipharís hyenas. Itís right up there with the taxidermy attack in Jesus Francoís Count Dracula.) The twinsí mother, Agatha (Joyce Grenfell), looks harmless enough, channeling her craziness into literally hundreds of miles per annum of useless knitting, but the way she talks about her perpetual project puts me strongly in mind of the three Fatesó and you remember what was supposed to happen when Atropos snipped off her sistersí threads. Morganaís father, Morgan (Danny Green, from Murder at the Baskervilles and The 7th Voyage of Sinbad), is the most visibly dangerous of the lot, harboring a psychotic jealousy of his daughter, and being generally assumed to have killed all of her previous suitors. As for Roderick, his gun collection could outfit a respectable Third World military, and of all the Femms, heís the most openly conscious of the family legacy as a zero-sum game. Now ordinarily it might seem that Tom personally has nothing to worry about except for steering clear of Morgan after Morgana sets her sights on him, even once Casperís killer begins working on the rest of the clan. However, there happens to be a legend about a little-known American side of the family, and Roderick thinks he detects a resemblance between Penderel and the portrait of old Morgan the Pirate that hangs in the chateauís drawing room.

Before we go any further, I want to remind you all of my utter loathing for James Whaleís interpretation of The Old Dark House. I consider it easily the worst major-studio horror movie of an era in which major-studio horror movies more often than not were clumsy, anemic affairs, of more academic interest than actual artistry or entertainment value. So when I tell you that William Castleís The Old Dark House reeks in the nostrils of the Muses, you will know that it is not just loyalty to the original talking. Whatever imagined benefit of a Castle-Hammer alliance might draw you to this movie, I assure you, you wonít find it here. The only trace of normative Hammer-ness is a genuinely terrific setó and it was used to much better effect a bit later in The Kiss of the Vampire, anyway. The Castle touch, meanwhile, is represented only by a very modest gimmick indeed, an animated main title sequence by Charles Addams, which is far and away the best thing about the film. Otherwise, The Old Dark House is the kind of mess that any two-bit hack could have made. Danny Green, to begin with, is no Boris Karloff, and Tom Poston is no anybodyó although he seems, horrifyingly enough, to be aiming vaguely in the direction of Kay Kyser! Story logic is thin nearly to the point of nonexistence. Most notably, thereís no apparent reason at all for the Femms to pick this night in particular to begin exterminating each other. If you fail to unravel the mystery of the killerís identity, it will be only because you stopped giving a shit well before anything in the way of a clue was presented. The remake manages to be just as boring and pointless as the original, even despite having both five times the body count (including a double knitting-needle throat-stabbing!) and something faintly resembling a plot. And as with the old version, itís a tough call which is the bigger affront, that soul-sapping dreariness and inanity, or all the noxious anti-comedy. Whale at least was trying for something sort of sophisticated by the standards of his day, alternating poisonously unfunny comedy of manners with poisonously unfunny camp. Castle and screenwriter Robert Dillon, on the other hand, mostly just substitute random zaniness on the Crane Wilbur model, shamelessly reusing not a few gags that had been polluting the atmosphere of horror comedies at least as far back as The Monster in 1925. To be fair, there are also a few thoroughly botched attempts at the sort of gallows humor that AIPís writers were proving so adept with around the same time, but not enough to have rescued The Old Dark House from itself even if they had worked. Frankly, Iím not a bit surprised that the Hammer leadershipís reaction to the finished product was to send it straight to the vault, not releasing it domestically until 1966. Columbiaó perhaps also not surprisinglyó showed no such discernment.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact