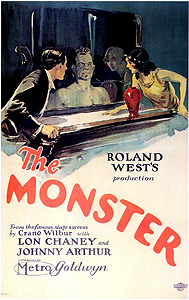

The Monster (1925) **

The Monster (1925) **

There are those who contend that this is the original mad doctor movie. That’s ridiculous. 1919’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari arguably counts as a mad doctor flick, the Edison Company released its version of Frankenstein way back in 1910, and the earliest known version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde came out two years before that. What might legitimately be claimed for The Monster is that it gave rise to all those “creepy old house full of loonies” movies that were so popular between the late 1920’s and the early 1930’s. In any event, The Monster is interesting enough, if only for its historical value, but suffers profoundly from a dearth of action and a bone-deep confusion about what sort of movie it’s supposed to be.

It gets off to a great start, though. In the middle of the night, on a lonely country road, a sinister-looking man in a black cloak (George Austin) lies in wait for passing motorists. From his perch in a tree overlooking the road, he sees a wealthy farmer (or so we are told by the intertitles) named Bowman driving toward him. The caped man lowers a huge mirror onto the road, with the result that Bowman sees his headlights reflected, giving the impression that another car is headed straight for his, matching his every effort to evade the collision. Finally, Bowman swerves completely off the road, his car tumbling down an embankment into the woods. The cloaked man and a raincoat-clad accomplice then pull the injured driver out of his wrecked car, and disappear with him into a tunnel concealed beneath a dense mat of creepers and moss.

The very next scene gives us much cause to worry. Several men from town are poring over the wreck of Bowman’s car, looking for any sign of the farmer himself. Included in the search party are constable Russ Mason (Charles Sellon), local dandy Amos Rugg (Hallam Cooley), and a young man named Johnny Goodlittle (Johnny Arthur). The division of screen-time during this scene suggests that Johnny is going to be The Monster’s central character, which is unfortunate because his behavior— to say nothing of the music that accompanies it— leaves no doubt that he is also going to be The Monster’s comic relief. Shit. I hate it when they do that. Anyway, Johnny wants to be a detective. He carries a how-to book on the subject around in his hip pocket everywhere he goes, and we will later learn that he has been taking a correspondence course for would-be private investigators. Naturally, Johnny finds the only thing even resembling a clue to Bowman’s disappearance, a small piece of paper with the words, “Dr. Edwards’s Sanitarium,” written on one side and the word, “help,” written so that it can be read only in a mirror on the other. And equally naturally, neither Mason nor Rugg considers Johnny’s find to be of any importance. After all, it came out of what used to be the trash heap for the asylum, which closed down months ago.

Jenkins, the detective called in to work on the case, doesn’t take Johnny or his clue seriously either. In fact, it seems like just about the only person in town who does is Betty Watson (Gertrude Olmstead), the daughter of the insurance salesman who also owns the general store where Johnny works. Johnny is in love with Betty, and Betty is rather fond of him, too, but matters are complicated by the presence of Amos Rugg. Not only is Rugg the suavest guy in the village, he’s also Johnny’s boss, and he too has a thing for Betty. Our hero obviously isn’t quite out of the running, though, because Betty invites him to the big party she’s throwing on Friday night. This invitation comes at a good time for Johnny, whose spirits have just been raised by the arrival in the mail of his detective school diploma and the badge, gun, and handcuffs that came with it. Now his fellow townspeople will have to take him seriously, right?

The party scene drags on way too goddamned long, particularly when you consider that its only real purpose is to put Betty, Johnny, and Rugg in the same place at the same time after dark. (Although it does provide some interesting hints as to popular mores regarding alcohol during the era of prohibition. An intertitle tells us that the party’s biggest attraction is the keg of cider the Watsons have stashed in the basement.) During a lull in the “action,” Johnny goes outside to sulk over his apparent inability to compete romantically with Amos, and while he is thus occupied, he runs across a very strange, obviously insane man in a curiously familiar raincoat (Knute Erickson), who asks him for a match with which to light his cigarette. When Johnny asks the man who he is, the stranger replies, “I don’t know,” and wanders off, muttering something about it being time to lower the mirror. Meanwhile, Amos has been turning up the heat on Betty, and has convinced her to go for a car ride with him. Those of you who remember the opening scene will have some inkling why this is an incredibly bad idea. Sure enough, the couple are snared in the caped man’s trap, at about the same time that Johnny, who had been following the smoking madman through the woods, falls into the hidden tunnel we saw earlier.

This fall (the tunnel is constructed like a long, underground sliding board) puts Johnny in what we can only conclude to be the parlor of Dr. Edwards’s supposedly defunct sanitarium. After all, we’ve clearly got two loonies roaming around in the woods— what better place to serve as their base of operations than an asylum? After much haunted hayride-scale creepiness, Johnny is joined in the locked parlor by Amos and Betty. The two men instantly begin sniping at each other, but all the bickering stops when Johnny notices what appears to be a dead body sitting in a chair in a darkened corner of the room. He and Rugg have just resumed arguing— this time over whether Johnny killed the sitter— when yet a third sinister individual enters the room through a door at the top of the staircase that dominates the parlor’s back wall. This is Dr. Ziska (Lon Chaney Sr., from The Phantom of the Opera and The Unholy Three), who claims to have taken over the asylum from Dr. Edwards. So much for the place being abandoned, huh? Ziska explains that the “dead” man is merely hypnotized; his name is Rigo, and he’s one of the doctor’s patients. (More importantly, he’s also the man in the black cloak, which raises the following question: how the hell did Rigo get into that chair when he was busy dragging Betty and Amos down to the asylum from their car?) Ziska then calls in his servant, Caliban (Walter James), to show his “guests” to their room. Given that Caliban looks like an executioner from a Sinbad movie, and he’s named after Shakespeare’s beast-man, this is probably not a positive development for Johnny, Betty, and Amos.

The three “guests” are, of course, locked into their room when Caliban leaves, and the men start arguing again. Betty shuts them up soon enough, however, when she finds a secret passage leading from the curtained-off sleeping area to who knows where. Johnny ends up with the unenviable task of investigating (hey, he is the detective here, right?), and at last some answers start materializing. The passage leads down to the basement of the asylum, and in a cell dug into the basement floor, Johnny finds Dr. Edwards, Bowman, and a third man whom the script never bothers to name. It seems Ziska, Rigo, Caliban, and Dan (the smoking crazyman) were all patients of Edwards’s, but that Ziska led them in a successful revolt against their keepers. Of the four lunatics, Dan is pretty much harmless, but that is far from being the case with the other three. Ziska had been a famous surgeon once, before his sinister experiments landed him in the asylum. Caliban is devoted to Ziska, and will do literally anything the surgeon commands. Rigo is a pathological killer, so dangerous that even Ziska must keep him under hypnosis at all times.

Meanwhile, back upstairs, Betty and Amos are in trouble. They may have been smart enough not to drink the drugged wine Caliban brought them, but Ziska has more tricks up his sleeve than that, and before long, both of them are being set up as subjects for Ziska’s experiments. Ziska hopes to use his electric chair to transfer Rugg’s soul into Betty’s body. Don’t ask me how— in fact, I rather think the patent impossibility of Ziska’s scheme is actually the point. So now Johnny gets his chance at last to prove himself to Betty, Rugg, and all the people in town who’ve been laughing at him all these years. Isn’t it uplifting? Doesn’t it make you want to puke?

Okay. There’s no question but that Lon Chaney Sr. was The Man. But even the best of them have a couple of clunkers on their resumes, and The Monster is one of Chaney’s. Its main fault is its creators’ inability to decide whether it was supposed to be a horror movie with moments of levity, or a comedy with horrific overtones. Such indecision is understandable in the context of 1925; genre confusion was rampant in those days, at least in Hollywood. This may be because filmmakers were still struggling to develop what might be called a language of conventions that would work in what was still a new medium. Not only that, art of any kind created for the express purpose of frightening its audience was a fairly recent innovation, and in the 1920’s, was looked on with intense suspicion just about everywhere but in Germany. To some extent, this cultural discomfort with horror is still with us three quarters of a century later. Writer/director Roland West (working from a play by Crane Wilbur) simply may not have had the nerve to sustain the mood of The Monster’s opening scene in the intellectual climate of his age, or perhaps the humor in the original play was mostly verbal and thus couldn’t easily translate to the screen in the silent era.

Finally, I would like, as a postscript, to draw your attention to Gertrude Olmstead, the actress who played Betty. From our vantage point at the turn of the 21st century, it’s hard to believe that the studio heads at MGM would ever have considered her viable as a female lead. She’s a very pretty girl, but she lacks completely the sort of improbable, almost unnatural beauty that we have come to expect from Hollywood actresses during the last 50 or 60 years. Not only does she look like somebody that mere mortals might know and indeed even hang out with, she actually has a major and conspicuous physical flaw: her eyes don’t line up right, giving the impression that she’s looking in two different directions at once. Can you imagine a time when independently targetable eyeballs wouldn’t have been deemed an unacceptable defect in the star actress of a major-studio movie? Neither can I, but the proof is right here.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact