Frankenstein (1910) [unratable]

Frankenstein (1910) [unratable]

It would take a very jaded person indeed not to be at least a little bit in awe of Thomas Alva Edison. Most inventors have one or at most a small handful of contraptions to which history attaches their names, but it sometimes seems like it would be quicker and simpler to list the things Edison didn’t invent, or at least have some role in perfecting. True, his reputation is inflated to some extent, since he wasn’t above making the occasional deal to market someone else’s gizmo as his own, but 1093 registered patents is a hell of a lot, no matter how you look at it. Any schoolchild knows that the incandescent lightbulb was Edison’s baby, and most adults probably at least dimly recall the part he played in the commercialization of electricity and the development of sound recording. What is not as widely remembered is his enormous involvement in the infancy of the motion picture.

Around 1888, shortly after his success with the phonograph, Edison began working with one of his most talented employees, William K. L. Dickson, on the problem of visual recording. The pair quickly settled upon a magic lantern approach using photographs taken at brief intervals, possibly inspired by the work of Eadweard Muybridge, whose Zoopraxiscope was almost literally a photo-based magic lantern. Of course, since most photos in those days— including the ones used by Muybridge’s device— were still taken on emulsified glass plates, the first thing Edison and his assistant were going to have to do was to devise some alternate photographic medium better suited to rapid sequential display. Then there were a host of other problems to solve regarding the machinery that would take those photographs, and the means of presenting them to the viewer. By 1891, Edison and Dickson had a two-part system consisting of a camera (dubbed the Kinetograph) and a display module (the Kinetoscope), the latter of which could be loaded with short loops of film (running about a minute at the absolute maximum, and frequently less than half that) viewable through a peephole at the top of the cabinet housing. The Kinetoscope was thus limited in both the nature of the films it could present (not much you can do with a 30-60 second running time) and the size of the audience it could entertain (only one person could look through the viewer at a time). It enjoyed a brief run of popularity spanning roughly 1894-1897, but was rapidly eclipsed by the French Cinematograph, which could exhibit its films to whole roomfuls of people by projecting their images onto a large external screen. (Note, incidentally, the conceptual similarity between the Edison Kinetoscope and the modern porn-shop peepshow booth. It is surely no coincidence that a sizeable fraction of the Kinetoscope loops shot at Edison’s studio featured scantily clad dancing girls.)

The obvious superiority of the Lumière Brothers’ technology led Edison to acquire the rights to a home-grown counterpart— which he renamed the Vitascope, and passed off as his own invention— and to begin experimenting with other projection systems that would later bear the original Kinetoscope name. And because the Gilded Age was the heyday of vertical integration in practically every industry, it was only to be expected that the Edison Company would commit significant resources to the creation of films that could be shown on their equipment. By exploiting much the same monopoly tactics as the major industrialists of the era (buying out financially struggling competitors, suing others out of business, and entering into collusive agreements with those too strong to be bested by either means), Edison was able to establish himself as the de facto tyrant of the American movie business, and it wasn’t until the establishment of the Hollywood enclave starting in 1911 that would-be filmmakers unaffiliated with Edison were able to get out from under his firm’s extremely heavy boot. The Edison Company kept its film studio and distribution network in operation until 1918, but the last six years were marked by steadily contracting market share. After all, the 1910’s were the era of D. W. Griffith; Hollywood was helping to lead a revolution in the style and technique of filmmaking, and the more conservative Edison production line simply could not keep pace. Their own success in cornering the market between 1900 and 1908 was surely part of the problem, for the lack of competition couldn’t help but encourage creative laziness, and as early as 1909, customer discontent with the studio’s output was running high enough that Edison sacked longtime production head Edwin S. Porter. The firm rallied for a couple of years, releasing some of the most ambitious movies in its history, but Edison was never able to regain the initiative from Hollywood.

Nearly a century later, the most celebrated product of the 1910-1911 resurgence is almost beyond question the Edison Company’s full-length (which in those days meant the full length of a single reel, or a bit less than fifteen minutes) adaptation of Frankenstein, although the film was a pretty complete failure upon its initial release. This was only two years after the earliest known narrative horror movie made on American soil, and the advance Frankenstein represented appears to have been considerable. Whereas the 1908 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was literally nothing more than a drastic abridgement of the stage play originally headlined by Richard Mansfield (who had died the year before), the Edison Frankenstein was shot from an original scenario by director J. Searle Dawley, and while Dawley’s direction was scarcely worthy of the name, the material aspects of the production were quite impressive by contemporary standards. Furthermore, this Frankenstein is the only one I’ve seen that follows the novel’s implied program for the monster’s creation, and the revisions to the second half of the story (presumably made with an eye toward avoiding the expense that Shelley’s original conclusion would have entailed) introduce an element of doppelganger horror to further differentiate this version from its successors.

Frankenstein (Augustus Phillips, from The Haunted Bedroom and the Edison Company’s one-reel version of The Bells) goes away to college, leaving behind his family and his girlfriend, Elizabeth (Mary Fuller, of The Ghost’s Warning and A Witch of Salem Town). After a scant two years of study (heaven knows nobody I went to college with applied themselves on anything like this scale), the lad has puzzled out the secret to creating life, and he writes to Elizabeth telling her that he intends to demonstrate his discoveries by creating an artificial man— and not just any man, either, but the most perfect human being ever to have lived. Needless to say, things don’t go precisely according to plan. Frankenstein’s creature (Charles Ogle, from The Witch Girl and Bluebeard) comes alive, alright, but it’s hunchbacked, misshapen, frizzy-haired, and all-around butt-ugly, and there’s something horribly wrong with its hands, as if they never quite got around to growing any skin on them. A fair sight short of perfect, in other words. Frankenstein wigs right the fuck out when he gets a good look at what he has made, and the monster, knowing when it isn’t wanted, slinks away.

It follows Frankenstein home, however, more than a little irate at how its creator has treated it thus far. Frankenstein, again, is horrified to see it, and would like nothing better than to have it go very far away. The creature has other ideas, though, and the ensuing quarrel quickly escalates into physical violence. Luckily for Frankenstein, his struggle with the monster occurs in front of a large mirror, and when it looks up and sees itself for the first time, the synthetic man turns out to be just as thoroughly repulsed as its maker. Again the creature withdraws, but it returns on Frankenstein’s wedding night, and makes itself known to Elizabeth while she is getting ready for bed. Elizabeth runs to her new husband for protection, he chases the creature off once more, and Frankenstein takes a sudden turn for the weirdly metaphysical— and for the weirdly metaphorical as well. By the time Frankenstein catches up to the monster, it has fled back to the room with the mirror, into which it somehow discorporates itself; when Frankenstein sees it in the glass, the monster gradually fades out into Frankenstein’s normal reflection.

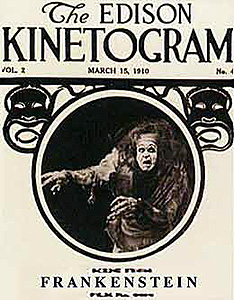

That ending owes a lot more to Robert Louis Stevenson than to Mary Shelley. The implication seems to be that although Frankenstein knew enough to create life, he was powerless to endow his creation with a soul— and so it took part of his to make up the difference. The intertitles, vague though they are, support such a reading: “The evil in Frankenstein’s mind creates a monster;” “The creation of an evil mind is overcome by love and disappears.” That is, the monster is an external embodiment of all Frankenstein’s worst qualities— his hubris, his jealousy (the intertitles constantly attribute the creature’s actions to a jealous nature), his capacity for violence— and Frankenstein’s love for Elizabeth, through which he rises above those faults, reunifies his psyche and puts an end to the creature’s independent existence. That Stevensonian reworking is most likely what the copywriter for the Edison Kinetogram meant when he wrote, in the March 15th, 1910, issue, “The Edison Company has carefully tried to eliminate all the actually repulsive situations and to concentrate its endeavors upon the mystic and psychological problems to be found in this weird tale. We have carefully omitted anything which by any possibility could shock any portion of an audience.”

It’s especially unfortunate, then, that J. Searle Dawley has gone so far to achieve the latter aim as to do serious violence to his efforts in the former department. Frankenstein’s monster is not very convincing as an incarnation of the evil in his soul, simply because it never quite gets around to doing anything that could be condemned as worse than mildly irritating. So solicitous and cooperative is it, in fact, that on its first visit to the Frankenstein house, it meekly obeys when its creator tells it to hide behind the curtains so that Elizabeth won’t see it. Furthermore, the one genuinely evil act we might surmise it to have attempted is apparently illusory, implicitly denied by the synopsis in the Kinetogram write-up. We know from the book that the monster has it in for Elizabeth, seeing in her the perfect weapon to use against Frankenstein in revenge for his callous abdication of the responsibility he incurred by giving the creature life. We also know (based not only on the book, but on any number of subsequent film versions as well) to expect an attack on her— and if we’re acquainted with the stage play from which the 1931 movie was derived, we’re apt to read that attack as sexually motivated. (Louis Cline, who script-doctored the version of the play that toured the US in 1931, described the scene thusly: “The Monster is to tear off Amelia’s gown, which gown is a breakaway affair, and leaves her as nude as the censors will allow. Then he is about to mount her in a rape. Before the scene gets too frankly sexy, the Monster is interrupted by a sound outside the window or door.”) And again, we’ve been told repeatedly in this movie about the creature’s jealousy, which makes a bid to rape Elizabeth seem like the natural way for it to establish its monstrous credentials at last. But Edison’s promoters were at pains to emphasize (in their ancillary materials, if not in the film itself) that the monster is jealous not of Frankenstein’s relationship with Elizabeth, but rather of his non-relationship with it. The monster wants Frankenstein all to itself, and Elizabeth is in the way. That being the case, we can safely conclude that, whatever the monster gets up to off-camera in its few seconds alone with Elizabeth in her bedroom, it isn’t supposed to be the libidinous assault that modern viewers will most likely imagine. The creature’s malefice is thus confined to a pair of playground-scale grapples with Frankenstein and the theft of a flower, making it just about the most miserably under-performing embodiment of evil ever, and making a hash of the most interesting idea this movie has to offer.

Luckily, Frankenstein is still closely enough in touch with the spirit of the previous decade’s trick films to give it some visual appeal, making up for its serious dramatic shortcomings even despite Dawley’s intensely archaic one-shot-per-scene directorial technique. Charles Ogle’s monster makeup (which he apparently designed himself) is as eye-catching as it is primitive, and as with the best renditions from later years, it leaves enough of his face free for him to get some real acting done. Viewers who are accustomed to thinking of the Frankenstein monster as a patchwork of limbs and organs harvested from stolen corpses will find the character design a bit puzzling, I expect, but that merely means that this Frankenstein is truer to the novel in that regard than any of its successors. For although Mary Shelley did have Frankenstein rob graves and mortuaries for raw materials, a close reading of the novel makes it very clear that he wasn’t simply sewing the best bits together into a new whole. So far as can be discerned from Shelley’s deliberately vague and obfuscating prose, the monster’s creation was primarily the result of quasi-magical biochemical and electrochemical processes, the necessary ingredients extracted and distilled somehow from all those pilfered bones and bodies. That’s how Dawley plays it in the creation scene here, too. Frankenstein mixes up a bunch of heaven-knows-what in a cauldron, seals the cauldron up inside a huge oven-like device, and then watches through a peephole as his creature gradually takes shape from the skeleton out. The trick is simple, but ingenious. Dawley built an articulated, multi-layered model of the monster, set it on fire, and then filmed it as it burned to ashes. Then he ran that footage backwards to produce the illusion of the creature’s body knitting itself together out of dust and vapors. It’s one of the most impressive sights in all of pre-modern horror cinema, more than compensating for the stultifyingly static approach that Dawley takes to literally everything else in the film.

This review is part of a B-Masters Cabal roundtable focusing on the olden days, when you had to bring along your reading glasses when you went to the movies, but never had to contend with the booming of the explosion flick in the auditorium nextdoor intruding upon your enjoyment of the sensitive relationship drama you were trying to watch. Click the link below to peruse the Cabal's collected offerings, and don’t mind the smell— that’s just the nitrate in the film stock rotting away to vinegar vapor before our noses...

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact