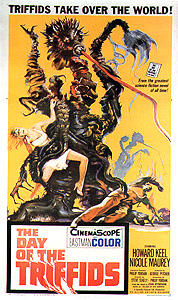

The Day of the Triffids (1962) **Ĺ

The Day of the Triffids (1962) **Ĺ

This is another movie that I like a great deal more than I can really defend. Yes, Iíve read the John Wyndham novel from which The Day of the Triffids derives, and yes, I realize that the film version represents a rather remarkable dumbing-down of the source material. Yes, Iíve noticed that the two parallel plot threads never actually intersect, nor indeed do they ever go much of anywhere individually. And yes, I did pick up on the fact that the titular plant creatures are handled very strangely, almost as if it wasnít until the shooting was well advanced that the filmmakers realized the triffids were going to be the primary focus of the second half. Having conceded all of those points, I now invite you to notice me not caring. In fact, Iíll go so far as to admit that I actually prefer this knuckle-dragging version of the tale to Wyndhamís. In the novel, the monster yarn and the social commentary keep getting in each otherís way, but the movie has no such identity issues. It seems to know that the sort of thoughtful, sober end-of-the-world story Wyndham attempted to tell is beyond its capabilities, and it spends little time on fruitless exertions in that direction.

So what, you may ask, is a triffid supposed to be, anyway? Well evidently a meteor landed in Britain some years ago, bringing with it the seed of an extraterrestrial plant. That seed unexpectedly germinated when it was introduced to our planetís soil, and the resulting plantó dubbed Trifidus due to its distinctive three-stalked body planó is now ensconced in the Royal Botanical Gardens in London. As we take up the thread of the story, the Earth is undergoing a meteor shower of unprecedented scale and intensity, with natural fireworks lighting up skies all over the world as the space rocks burn up and explode in the atmosphere. Something about the frequency of the light from those explosions has a very curious effect on the triffid, triggering a sudden, extreme growth spurt. And now that it has reached maturity, the triffid exhibits a previously unsuspected capability, uprooting itself from the ground, wandering off after the night watchman, and eating him after stinging him to death with the venomous tendril that emerges, tongue-like, from the blossom at the end of its central stalk.

The triffid at the Botanical Gardens isnít the only thing being affected by the radiation from the exploding meteors, either. Everyone who spent more than a few seconds watching the celestial showó and with all the media crowing about how this was a once-in-a-lifetime event, that means damn near everybody who was physically capable of doing soó has been blinded by the rays, not just their retinas but the optic nerves themselves burned away to useless nubs. Ironically, one of the few people to make it through the night with his vision intact is American seaman Bill Masen (Howard Keel), who had been in a London hospital, convalescing from some manner of eye surgery. His surgeon, Dr. Soames (Curse of the Demonís Ewan Roberts), had insisted that he keep the bandages over his eyes for the full ten days, even though Nurse Jamieson (Colette Wilde, from Circus of Horrors) was to have removed them first thing the following morning. Masen is astonished by the scene that confronts him at 9:00 AM, when impatience ges the better of him and he undoes the dressing himself. The hospital outside his private room is trashed, and there doesnít initially seem to be anybody in it. Then Masen runs into Dr. Soames, and learns to his horror what has happened.

That horror worsens considerably when Masen gets out onto the street, and has a look at the shambles that London has become. At a train station, he rescues a girl named Susan (Janina Faye, from Horror of Dracula and The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll) from a big, belligerent man who had attempted to press her into service as his bipedal seeing-eye dog, and then witnesses the appalling destruction when a locomotive with a blinded conductor smashes itself to pieces at the platform. Masen has a similarly rotten experience at the dockside, where he hopes to make a getaway aboard his ship; an airliner (which had exhausted its fuel while the blinded crew attempted to make radio contact with someone who might direct them into a more or less safe landing) falls out of the sky and into the vessel at the next pier, touching off an inferno that eventually consumes the entire port. Fortunately, there is a much more manageable boat moored at a wharf beyond the blazeís initial reach, and Masen is able to get it up and running to take him and Susan across the Channel to France.

Now, about those triffidsÖ The specimen from the Botanical Gardens is no longer the sole representative of its species on Earth. The same meteors that blinded the vast majority of the human race have also brought millions of triffid seeds, and these quickly take root wherever they find sufficiently nourishing soil. The new triffids grow rapidly (one assumes that the immense meteor shower must have made some permanent, triffid-friendly alteration to the Earthís ecosystem), and soon begin roaming the countryside, preying on the nearly helpless masses of freshly blinded humanity. They also begin propagating seeds of their own.

Meanwhile, in a lighthouse on an island somewhere, marine biologist Tom Goodwin (Kieron Moore, of Dr. Bloodís Coffin and Satellite in the Sky) and his wife/assistant, Karen (Janette Scott, from Paranoiac and Crack in the World), have been too busy to fry their optics with ill-advised stargazing. The couple are supposed to be doing some kind of work with stingrays, but really, Tom spends most of his time at the lighthouse getting his drink on while Karen futilely tries to motivate him toward their research. Life on the island gets a great deal more interesting (isnít there an old Chinese curse about that?) when triffids begin taking root there, giving Dr. Goodwin something he absolutely canít afford not to study. While the main storyline unfolds elsewhere, the Goodwins will struggle to defend their lighthouse against the increasingly aggressive plants, searching at the same time for some means of destroying them.

It is in France that the triffids first become a serious problem for Masen and Susan. They fall in with a man named Coker (Dead of Nightís Mervyn Johns, who was also in William Castleís remake of The Old Dark House), who takes them back to his rural mansion, which he and his neighbor, Christine Durant (Nicole Maurey), have converted into a sort of makeshift charity house for the blind. (Coker and Durant escaped blindness in much the same way as Masenó they were both hospitalized due to injuries sustained in a car crash with each other.) This cozy arrangement doesnít last long, however, partly because a gang of looters with working eyeballs set their sights on the Coker estate, and partly because a veritable plantation of triffids has cropped up only a mile or so away. The alien plants make their presence felt just as Masen is attempting to rescue Christine from the hooligans, and the two of them (accompanied by Susan) donít stop fleeing until they reach the NATO navy base at Toulon. (France was still part of NATO in 1962.) Masen had been hoping to hop a ship back to America, but Toulonís port is in about the same shape as Londonís was when he and Susan left it. Not to be discouraged even by this tremendous setback, Masen immediately rounds up the women, and sets off for Cadiz in Spain, where there is another NATO naval installation. They get held up on the way, though, when they encounter Luis de la Vega (Geoffrey Matthews) and his wife, Teresa (Gilgi Hauser). Both of the de la Vegas are blind (Teresa has been that way for years, as a matter of fact), and Teresa is due to give birth any day now. Luis persuades Masen and his companions to stick around and help with the birth, and to bring the de la Vega family along to Cadiz as soon as Teresa is fit to travel. The triffids reach the house long before she can be moved, however.

Ever since I was a small child, Iíve had an irrational aversion to big, weird plants, and Iím sure that goes a long way toward explaining why The Day of the Triffids appeals to me so much more than it truly deserves to. It helps a great deal that the creatures themselves are unusually well realized by the standards of 1962, especially considering that this movie was made by a tiny British company, and distributed by a descendant of Hollywoodís Poverty Row. Apart from a few scenes in which the seams show glaringly (those occasions on which a triffid is required to ascend a staircase are particularly laughable), the monsters are convincingly plant-like, benefiting enormously from an honest effort to follow the form described by John Wyndham instead of, say, falling back on a design that could have been easily realized by a man in a rubber suit. Because the triffids are really only marginally animate anyway, the movie actually benefits from the extremely limited mobility of the large puppets used to portray them. The rest of the special effects (the meteor shower, the plane crash, etc.) are less successful from the standpoint of representational realism, but a few of them manage to attain the cooler-than-real look that one encounters from time to time in carefully crafted 1960ís horror, sci-fi, and fantasy films. And the huge triffid army that lays siege to the de la Vega house during the main castís half of the climax is extremely effective, even if it is a blatantly obvious matte painting.

The Day of the Triffids also boasts a handful of potent moments that have little or nothing to do with the monsters. The fate of Dr. Soames early on is a brilliantly handled affair, and Masen gets a few character bits throughout the film that enable Howard Keel to rise a little above the level of the typical 60ís B-movie leading man. Janina Faye is quite good for her age as Susan, even if she does occasionally get dragged down by another actorís sub-par performance opposite her. And perhaps most importantly, The Day of the Triffids succeeds once in a while in capturing a glimpse at the horror of society as we know it coming completely unglued. This is still the sort of movie that someone in search of more than a pleasurable monster matinee will have to sift carefully in order to find the good stuff, but it does indeed reward such sifting to some extent.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact