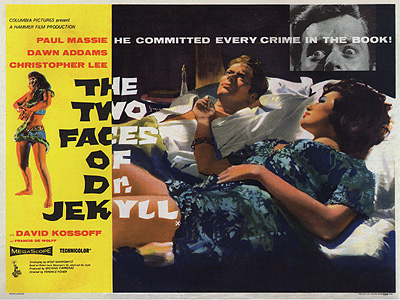

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll / Jekyllís Inferno / House of Fright (1960/1961) ***Ĺ

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll / Jekyllís Inferno / House of Fright (1960/1961) ***Ĺ

To the best of my knowledge, there has never been a truly faithful film adaptation of The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and itís much too late to try making one now. Robert Louis Stevenson handled the story like a mystery, revealing that Jekyll and Hyde were the same person as a twist ending; obviously that would never fly today, and given the international popularity of the novella and stage play throughout the Edwardian era, it might already have been a non-starter when Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde was filmed for the first time in 1908. Consequently, itís not fidelity that I look for in a Jekyll-and-Hyde movie, but astute reinvention. I want to see creative interpretations and expansions of Stevensonís themes, new angles on the duality of the title characters, clever approaches to the vexed question of why someone who wasnít already evil would undertake a research program like Jekyllís in the first place. The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll, the second of Hammer Film Productionsí three takes on Stevensonís story, delivers on all those fronts and then some. Easily the most radical adaptation of the novella yet mounted in 1960, it remains a fair contender for that crown even today. It takes the premise behind the previous yearís comedy, The Ugly Ducklingó dumpy megadork Dr. Jekyll becomes glamorous, amorous dandy Mr. Hydeó and handles it not just with complete seriousness, but even with what looks like philosophical rigor by horror-movie standards. Most remarkably, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll engages the issue of Victorian morality (a central concern of nearly all versions of this story) from a direction Iíve never seen before. Rather than attack or defend Victorian morals directly, this film treats it as a foregone conclusion that theyíre fucked up and inadequate, and devotes its energy instead to playing some possible alternatives against each other.

Weíve talked before about how the biggest stumbling block for any Jekyll-and-Hyde story is the need to justify or at least excuse Jekyll transforming himself into a monster. This version sidesteps the whole issue by ditching the notion that the difference between Jekyll and Hyde has anything to do with one of them being good and the other evil. Its Henry Jekyll (Paul Massie) is avowedly a post-humanist, although of course that term hasnít been invented yet in 1874. His work in developmental psychology (yet another thing his time doesnít properly have a name for) has convinced him that our species has the potential to evolve into creatures of perfect reason, perfect justice, and perfect compassion. However, there also exists a contrary potential, a chance to attain perfect selfishness and the untrammeled pursuit of desire. The humans of today might look at such beings and call the former ďgoodĒ and the latter ďevil,Ē but in Jekyllís view, that would be a mistake. Our morality is based on conscious choice between the behavioral patterns that we define as good and evil, but the behavior of these post-humans that Jekyll imagines would be driven completely by the imperatives of their nature. One might just as well make value judgements about the actions of sheep or crocodiles. Nevertheless, it should be obvious that the average personís lot in life would be improved if our evolution could be guided onto the ďangelicĒ track, and made considerably worse if we evolved into mortal ďdevilsĒ instead. Jekyllís scientific mentor, Professor Ernst Litauer (1984ís David Kossoff), thinks that whole line of reasoning is just so much theoretical tail-chasing, but the younger doctor has been looking into ways to force exactly the transformation he describes. Before he can launch a race of angels, however, he believes he must first find out what makes devils tick, and he is close to perfecting a drug that can temporarily isolate the Id Monster that lurks inside every human psyche.

Unsurprisingly, that kind of work takes lots and lots of time, and given the reaction that the project is sure to elicit from those who like humanity just the way it is, it also demands absolute privacy. Jekyll has therefore made himself a recluse even within his own home, and his wife, Kitty (Dawn Addams, from The 1000 Eyes of Dr. Mabuse and The Vampire Lovers), is thoroughly sick of it. Sick enough, in fact, to strike up an affair with her husbandís best friend, Paul Allen (Christopher Lee). Paul is the very model of a 19th-century European libertine: a gambler, a drunk, and a habituť of music halls and whorehouses. Thatís just what Kitty now finds she wants, though, even if she does disapprove of all the money Paul loses at the card table, and then borrows from Henry to keep his creditors at bay. The arrangement is actually just as beneficial for Jekyll as it is for the adulterers, when you really think about it. Every night Kitty spends out on the town with Paul is one she canít spend annoying her husband by barging into his laboratory and demanding to be acknowledged, as well as a night Paul canít spend gambling away his friendís money. Henry has never had a chance to ratify the scheme, though, since Paul and Kitty have been in no hurry to tell him what theyíve been up to.

As fate would have it, itís precisely Henryís success in the work that drove his wife to cheating that leads him to discover her infidelity. Following a promising line of animal experiments, Jekyll tries out his devil drug on himself, resulting in the emergence of a new personality with altered physical features to match. But instead of being crabbed or puffy-faced or downright simian as weíve been led to expect by 52 yearsí worth of previous films on this theme, the new Jekylló call him Edward Hydeó is younger, handsomer, and more vigorous than his usual self. Hyde also has no patience for Jekyllís monkish lifestyle, and no sooner has he manifested than he scoots off to the Sphinx, one of Londonís most stylishly sinful night spots. That happens to be the very same place where Paul took Kitty, whom Hyde is quick to notice among the crowd. He introduces himself as an old friend of Jekyllís, and proceeds to horn in on the coupleís date most shamelessly. Allen, drunk as fuck anyway and no hypocrite when it comes to women, is happy to relinquish the role of Kittyís dance partner for a while. She finds Hyde thoroughly charming as well initiallyó that is, until something he did earlier in the evening catches up with him. The Sphinx is prime hunting ground for whores, and Hyde had his eye on a few of those before he spotted Kitty. The prostitute with whom he was dancing at the time took great exception to being ditched so rudely; while Hyde befriended Kitty and Paul, the jilted hooker told her pimp (Oliver Reed, from These Are the Damned and Paranoiac, in his first role for Hammer) all about the incident. Now the pimp takes it upon himself to educate Hyde in the proper way to treat a lady (ladies of the night included), but he hasnít figured on Hydeís unique personal qualities. Eddie isnít a man to be bullied, even when the woman heís trying to impress is visibly displeased with his behavior. Kitty knows that sheís skipping out on an ugly scene when she storms out of the Sphinx amid a cloud of testosterone fumes, but she has no idea how ugly it nearly becomes. Only the timely intervention of a legitimately shocked Allen prevents Hyde from beating the defeated pimp to death with a lead candlestick from a nearby table. Hydeís violence is equally shocking to Jekyll, who reasserts himself strongly enough to force his alter ego back home for a reverse transformation.

Jekyll vows never again to use the drug that turned Hyde loose, but we know heís going to break that vow even before his remorseful attempt to patch things up with Kitty goes nowhere. Sure enough, Hyde is soon back at the Sphinx with Allen, taking in the performance of a foreign snake-dancer called Maria (Norma Marla, whoíd already done the Jeyll-and-Hyde thing once before in The Ugly Duckling). Rumor has it that Maria isnít above turning the occasional trick, but Paul cautions his new friend that her standards are too exacting for the likes of them. Naturally, that just makes Hyde more determined to bed her, and damned if he doesnít succeed through sheer audacity. Then he gets an even more audacious idea: wouldnít it be a hoot and a holler to seduce Kitty? To have, in effect, an illicit affair with his own wife? Hyde has misjudged Mrs. Jekyll, however. Although sheís no more inclined to stand on propriety than Pauló or even than Maria, for that matteró she has come to find Hyde even more repellant than her shut-in husband. Furthermore, while it may be true that her dalliance with Paul began as a way to relieve her loneliness and boredom, the truth is that sheís now in love with him. Hyde can fuck right off if he thinks heís getting in the way of that! Any fucking off on Hydeís part is purely tactical in nature, though. With truly diabolical inventiveness, he starts positioning himself as Paul Allenís personal bank, making up for Jekyllís sudden reluctance (brought on by what Hyde saw that first night at the Sphinx) to underwrite his friendís carousing. Once Allen is up to his eyeballs in hock to him, Hyde proposes to blank out the whole ledger if Paul will lend him Kitty for a while. Impressively, that proves to be the one point on which Allen is capable of making a firm ethical stand, and Hyde is thwarted once again. Very well. I guess itíll just have to be revenge, now, wonít it?

Jekyll, meanwhile, is having one of those dark nights of the soul you hear about. The Hyde drug is having serious physical side effects, accelerating his metabolism so that he ages noticeably every time he changes back into himself. Heís sick at heart over everything his alter ego does, yet heís also acutely conscious of how much more satisfied with life he is as Hyde. Itís getting to the point where Jekyll seriously contemplates giving up on himself altogether, and disappearing permanently into his artificial second personality. In the end, itís the vile thoroughness with which Hyde pursues his vendetta against Kitty and Paul that turns Jekyll against him, resulting in a drawn-out battle in which Hyde devises ever more ghastly crimes to pin on Jekyll, hoping to force him into surrendering control of their shared body as the only means of escaping punishment. What Hyde does not realize and can never understandó and what therefore places him at a disadvantage in his struggle against Jekylló is that the doctor is still human in that moral sense we were talking about before, and therefore capable of making the choice to sacrifice crude self-interest for the sake of something greater and nobler.

The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll represented an attempt by Michael Carreras to take Hammer upscale. The past five years, and the past three years especially, had seen the studio rise in status from inconsequential programmer factory to one of the most influential independent film studios in the world, and Carreras wanted to put the Hammer name on something more mature and respectable than their usual fare. Of course, it wouldnít do to alienate the customer base that drove the companyís ascent, so that prestige product needed to fall somewhere within the traditional confines of the horror genre. The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde must have seemed like the perfect basis for such an undertaking. Earlier adaptations had been among the most accomplished and highly regarded fright films of the 20ís, 30ís, and 40ís, and the source material was rich enough that even very minor variations like The Son of Dr. Jekyll often turned out better than one would expect. The Jekyll-and-Hyde story also had a strong tradition onstage as a vehicle for heavyweight acting. The dual title role had been reckoned a plum part since the late 1880ís, attracting top talent in all the nexuses of English-speaking drama. That stage history is particularly relevant to The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll, for rather than entrust the screenplay to a Hammer regular like Anthony Hinds or Jimmy Sangster, Carreras went outside the company to recruit Wolf Mankowitz, a playwright from Londonís West End theater scene. The final element of The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyllís bid for a new level of critical esteem was a big financing buy-in from Columbia Pictures, which despite its relatively weak position in Hollywood still had far more money to spend than Hammer. No one well acquainted with the history of horror movies in Britain will be surprised by what came of these efforts to classy up the Hammer brand. The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll was condemned to commercial failure by the very qualities that make it artistically impressive.

Mankowitz, to begin with, was an interesting creative mismatch with Hammerís company culture. As weíve discussed before, for all the flack the studioís gothic horror films took from censors, they actually display a staunchly conservative moral sensibility. The Curse of Frankenstein, Horror of Dracula, The Mummy, and their successors deal in stark extremes of good and evil, law and chaos, right and wrong, and can almost always be counted upon to side with the established order in deciding which is which. Itís one of the reasons why Hammerís output seemed so stodgy and old-fashioned in the more skeptical pop-culture environment of the 70ís. Mankowitz, if his work here is any indication, would not have had that problem. Nobody in The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll lives according to professed Victorian social or sexual norms, except for Dr. Litauer and a few minor characters whom we just barely see anyway. Hell, itís implied that the police inspector (Francis De Wolff, from The Black Torment and The Clue of the Twisted Candle) who gets involved when Hydeís battle for supremacy over Jekyll starts racking up a body count is normally on the take from the management at the Sphinx. And more remarkably, it never seems like the filmmakers are condemning any of these people for their lifestyle choices, even though almost literally everyone in the film comes to a bad end. Kitty and Paulís love for each other is shown to be real and committed, adulterous or not. Maria is treated not as a sinner reaping her just reward, but as someone who disastrously misjudged a riskó and nevermind that sheís basically a highfalutin whore. Mankowitz even shows some sympathy for the family of thieves who roll Hyde when he goes out to drown his sorrows after being rejected by Kitty a second time. But the most shocking departure of all from the usual Hammer moralism might be how everybody initially responds to Hyde. Wherever he goes, Hyde makes a winning first impression, precisely because he so openly doesnít give a fuck about the rules. Only when they realize that heís legitimately dangerous do people try to distance themselves from him. Itís hard to put my finger on how this differs from Hammerís portrayal of Victor Frankenstein as a charismatic sociopath, but it does. Maybe the key is that in the Frankenstein movies, itís the audience thatís attracted to a psycho against their better judgement, while the other characters almost to a one justifiably find him appalling. In any case, director Terrence Fisher was most discomfited by Mankowitzís script. He tried to compensate for what he saw as the movieís lack of a moral center by making Hyde an even more unapologetically complete monster, but his tinkering actually intensified the supposed problem. Now Hyde was doing things truly beyond the pale of acceptability for early-60ís movie villains, and the non-judgemental treatment of figures like Paul and Maria created the sense he might, just maybe, get away with them in the end.

I have no idea how The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll made it past the British Board of Film Censors at all, unless it was simply that it was Hammerís least gruesome horror movie to date, decorously devoid of organ-harvesting, corpse-animating, and arterial spray. Critical opinion was no less brutal than usual, though, and the paying public took less interest in the picture than they had in practically any Hammer production of the past five yearsó quite possibly because The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll was the companyís least gruesome horror film to date. In the end, Michael Carrerasís intended ticket to the big leagues lost Hammer some £30,000, or roughly a fifth of the filmís production cost. Columbia, meanwhile, had it even worse. As signatories to the old MPPDA Production Code, they were pledged to release nothing that would violate its terms, yet even after dialogue overdubs and eight minutesí worth of cuts, The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll still violated most of them. The movie Columbia had helped bankroll in exchange for its American distro rights was unreleasable without endangering the studioís membership in the Motion Picture Association of America (as the MPPDA was renamed in 1945), leaving no alternative but to sell it to some outfit that wasnít a member of the club in the first place. That outfit wound up being American International Pictures, whose lowbrow customers rejected The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll twice, as both Jekyllís Inferno and House of Fright. Once again, I suspect that the absence of both blood and monsters was the problem, especially since the US cut was missing most of the sexy stuff, too.

The upshot of it all is that The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll is a cult movie still waiting for its cult to emerge. The most ambitious horror film Hammer ever made, and the most subversive until Twins of Evil, it would be worth a look for what it tries to do and be even if it were a total failureó which it most assuredly is not. To return to what I said earlier about astute reinvention, thereís scarcely a single trope of the Jeyll-and-Hyde premise that this movie doesnít turn upside down or inside out. Hyde is handsome while Jekyll is homely, and itís Jekyllís appearance that worsens with each transformation, as the side effects of his formula prematurely age him. Instead of Jekyll having two women who want him, Hyde has two women whom he wants, and the Ivy analogue dies because Jekyll forces a transformation while sheís alone with Hyde. And in my favorite reversal of all, Hydeís predatory slum-prowling results in him being beaten and robbed! Now all that stuff is clever, but itís the thematic expansions that bring this movie to the threshold of greatness. First and foremost, Jekyllís normally ill-motivated experiments make perfect sense here. This Henry Jekyll is a scientific utopian looking to improve the fundamental nature of man. He creates Hyde not because he believes for some unfathomable reason that it would be intrinsically desirable to do so, nor even out of pure curiosity, but because he regards it as a necessary prelude to creating the ‹bermensch that is his true goal. And the late 19th century, you may recall, was a boom time for scientific utopianism. Eugenics, psychotherapy, mesmerism, and a hundred quackish ďlife reformĒ movements got their start in those days, all of them seeking to unlock some hidden potential of our species through the application of some newly discovered scientific (or ďscientificĒ) principle. Thatís the context in which we should be looking at Jekyllís research, at least at first. Heís a decent and well-intentioned man who believes, in his colossal arrogance, that he might remake humanity as easily as cultivating a new hybrid strain of orchid. Then later on, he continues the work past the point where its downside becomes glaringly apparent for all too plausible a reasonó his self-pity over being betrayed by the two people closest to him, contrasted against the thrilling confidence and self-certainty that comes with being Hyde.

Only three things prevent this movie from reaching quite the heights it should have. The first is little more than a nitpick, albeit a nitpick that arises at the worst possible time: Paul Allenís rather ludicrous death scene, which asks us to believe either that Maria performs with some hitherto unknown species of venomous snake that happens to look exactly like a ball python, or that so tiny a constrictor could bring down a man as gigantic as Christopher Lee in his prime. The second arguably has more to do with my expectations than with the quality of the movie per se, but I canít help docking a few points for setting up a thematically perfect ending, and then turning aside from it at the last minute. My final ground of objection is sufficiently pervasive, though, that I donít feel even a little bit bad griping about it. Simply put, Paul Massie doesnít give either Jekyll or Hyde quite what the part needs. He certainly isnít bad, but heís off in some small yet serious way. Too exaggeratedly morose as Jekyll, too theatrically stiff as Hyde, and just plain artificial in general. The Two Faces of Dr. Jekyll might be the only Jekyll-and-Hyde film Iíve ever seen where the performance of the actor in the title roles is the least memorable and impressive thing about it.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact