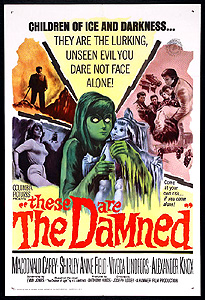

These Are the Damned/The Damned (1961/1963/1965) ****

These Are the Damned/The Damned (1961/1963/1965) ****

Hammer Film Productions ought to be better remembered for its contribution to the cinema of science fiction. Admittedly, the studio made relatively few such films, and nobody paid much attention to them until Val Guest added horror to the mix with The Creeping Unknown, but even outside of the Quatermass trilogy, Hammer did some very impressive work in the genre. Most notably, they made These Are the Damned, which should by rights have eclipsed even the Quatermass films. From both the title and the involvement of a group of very strange children, you’d assume this movie was nothing more than an attempt to cash in on the success of MGM-UK’s Village of the Damned, and from the perspective of the studio heads, it might actually have been. Writer Evan Jones and director Joseph Losey made something a great deal more substantial of it, however, and These Are the Damned unexpectedly exceeds Village of the Damned in many respects, including some that were among the earlier film’s strongest points. But as was so often the case in Britain during the early 60’s, the very qualities that gave this movie its power also caused such consternation among censors and critics that These Are the Damned was packed off as quickly as possible into disdained obscurity after having its release held up for some two years. Nor did it fare much better overseas after a further two-year delay, its American distributors apparently having little idea what to do with something so mannerly that was simultaneously so utterly bleak.

These Are the Damned won’t be playing its John Wyndham card for a while yet. Far from mysterious outbreaks of unconsciousness or waves of inexplicable pregnancies, we begin instead with a somewhat loutish American tourist named Simon Wells (Macdonald Carey, from End of the World and It’s Alive III: Island of the Alive) on vacation at a resort town somewhere along the southern coast of England. An attractive girl (Shirley Anne Field, of Peeping Tom and Doctor Maniac) catcalls Wells while he stares up at the clock tower in the town square, and Simon tries his hand at picking her up. It’s really just a trap. Simon’s gawking has exposed him as an out-of-towner, and because non-natives mean money at coastal resorts, the rocker gang (universally misidentified as Teddy boys, even within the film itself— at least we Americans have an excuse for not knowing the difference between the two tribes) with which the girl runs has marked Wells for beating and robbery.

Meanwhile, in a nearby coffee shop, an elderly scientist called Bernard (Alexander Knox, from The Psychopath and The Son of Dr. Jekyll) is receiving a visit from an old girlfriend of his, Freya Nielsen (Viveca Lindfors, of The Corpse Collectors and Creepshow). Freya apparently drops in every year to spend the summer at Bernard’s cliff-side beach house, which the locals have somewhat snidely dubbed the Birdhouse as a consequence. She’s a sculptor, and she finds that the forbidding solitude of the Birdhouse focuses her creative energies and enables her to do far and away her best work. Bernard, on the other hand, can’t talk about whatever he does for a living. It’s military-funded and top secret, and I really don’t think he’s kidding when he tells Freya that to confide in her would be to condemn her to death. Anyway, while the two of them are chatting, a pair of serious-looking men carry the battered and bloody Simon Wells into the café. By an interesting coincidence that may actually be nothing of the sort, Simon’s rescuers are Major Holland (Walter Gotell, from Circus of Horrors and The Boys from Brazil) and Captain Gregory (James Villiers, from Asylum and The Nanny), both of them soldiers attached to Bernard’s hush-hush project. Holland and Gregory need the scientist for something out at the lab complex, and Bernard goes off with them, leaving Wells to Freya’s ministrations.

A few hours later, Simon has his second— and more serious— brush with the rockers. While he relaxes on the deck of his boat, Wells is accosted again by the girl, who strikes up a very odd conversation with him. Turns out her name is Joan, and her brother, King (Oliver Reed, later of The Devils and The Pit and the Pendulum), is the leader of the gang that worked Simon over that morning. Joan seems not to approve completely of King’s lifestyle and behavior, and indeed she gives the impression of being at least somewhat frightened of her brother and his hooligans. But since she also professes to consider Simon a sleazy creep who thinks with his prick (he never so much as asked Joan her name when he was hitting on her earlier, after all), it’s hard to understand what she’s doing inviting herself onto his boat and airing her discontents with the life of a gang hanger-on. King’s motives, however, are perfectly clear when he and his boys arrive on the docks and surround Simon’s boat. He wants Joan to get her ass back onto dry land, and he’s got an eight-inch blade in the handle of his cane that says Wells is going to stay the hell out of any inter-sibling disputes. But Wells fires up his boat’s engines the moment Joan sets her feet on the wharf, and before long, he’s encouraging her to hop back aboard. Joan takes off running, and leaps down to the deck before King has formed more than the vaguest idea of what’s happening. Simon will have to bring Joan home sometime, though, and King means to be ready for Wells as soon as he does.

As for Bernard, he unexpectedly turns out to be in the teaching business, after a fashion. In a concrete warren beneath his fenced-off seaside lab live four girls and five boys, apparently about nine years old, who seem to have absolutely no contact with anybody other than him. And even that contact is strangely indirect, for Bernard will speak to them only via a closed-circuit television link between his office and their classroom. The children don’t like this, of course, but Bernard assures them that the separation is vitally necessary, for reasons which he will explain to them someday, when they’re mature enough to understand. The whole of the kids’ lair is wired with security cameras, so that it would be easy enough to keep tabs on all nine of them, 24 hours a day. Bernard doesn’t want to do that, however. In fact, his refusal to fully exploit the surveillance potential of the laboratory subbasement is a bone of constant contention between him and Major Holland, who would subordinate everything, if given the chance, to his twin obsessions of secrecy and security. Naturally, that means Holland stays tight-lipped even in front of us in the audience, but we do have one major clue to go on in puzzling out the mystery of the children under the lab. Bernard has an obsession of his own, you see, an appalled faith in the long-term inevitability of full-scale nuclear war, and it’s a safe bet that only something that played to that obsession could lead him to participate in a project that keeps nine children imprisoned for years in an underground bunker.

Simon and Joan encounter Bernard and his kids soon after they put ashore. Joan is reluctant to go back to town, for her own sake at least as much as for Simon’s. King nurtures a psychotic, incestuous jealousy of his sister, and refuses to countenance the idea of her having any other man in her life but him; I suppose being both a controlling sadist by temperament and a 25-year-old virgin in a subculture that puts great stock in simplistic metrics of masculinity might do that to you. Having both rebelled against King in front of all his followers and taken off to spend the day alone with a man, Joan understandably fears that her brother might become violent unless she delays their reunion until after he’s had a good, long while to cool off. So instead of taking her back to the docks, Joan has Simon put her ashore at the Birdhouse, where she has long been accustomed to hiding out from King’s more menacing rages. King means business this time, though, and his gang has kept the whole of the neighboring coastline under constant surveillance since Joan’s departure. King’s lieutenant, Sid (Kenneth Cope, from Island of the Burning Doomed and X: The Unknown), sees Wells’s boat come in, and Simon and Joan have only an hour or two of peace at the Birdhouse (Freya is in town when they land) before King and his minions descend upon them. The harried travelers seek escape the only way they can, by scaling the perimeter fence around Bernard’s lab complex, and they and King alike are soon hounded over the cliffs by Major Holland’s security forces. It is the children who rescue them, and as Simon, Joan, and King spend their next several days amongst the peculiar kids, it gradually becomes apparent that the latter are the centerpiece of an experiment into which the full horror of the Cold War has seemingly been distilled. The nine little children are all mutants, born with a superhuman resistance to ionizing radiation as the result of a nuclear accident that claimed all of their mothers mere days before the irradiated babies would have been delivered naturally. Bernard, with his terrible certainty that the Earth is doomed to atomic holocaust, has battened onto these kids as the final hope for humanity. The bunker is partly to protect them against the more immediately deadly effects of a nuclear exchange, but it’s also partly for the protection of their adult handlers and the inhabitants of the nearby settlement. For having absorbed in utero enough radiation to kill any normal person, the children are lethally radioactive themselves.

The most frightening thing about These Are the Damned is the way in which it illustrates how the pervasive pressures of the Cold War could transform lunacy into sanity, and vice-versa. Begin with Dr. Bernard’s thesis that global nuclear war is, in the long run, unavoidable— a thesis that seemed chillingly plausible even as recently as the early 1980’s. Assume further that the human race as it exists now cannot survive in a post-nuclear environment, a premise with which it would be difficult to argue even today. Now add to the equation nine children who, through an accident of birth, are perfectly adapted to life in a world poisoned by radiation. Suddenly, there is hope for the species after all, and Bernard’s bunker— flagrantly unconscionable in a sane world— becomes the only rational approach to the problem. Meanwhile, a similar process works the same transformative magic upon Major Holland’s neurotic (and ultimately murderous) drive for secrecy. Holland, Bernard, and their colleagues are forced, by dint of their professions, to live full-time in the upside-down moral universe of the Cold War, but they know perfectly well that the majority of the citizens for whose safety they supposedly labor will insist (like Freya Nielsen, who eventually becomes much more important than she initially appears) upon believing that the world is still sane, and that operations like Bernard’s are therefore still beyond the pale. People like Freya would demand that Bernard’s work be abandoned, sacrificing humanity’s last chance for survival in order to give nine individuals a normal childhood— individuals whose biological peculiarities almost certainly preclude anything like a normal childhood in the first place. It therefore follows that no one outside the lab must ever be allowed to learn of what goes on within it, and that the strictest measures must be taken to prevent anyone who does uncover the secret from passing it along to anybody else. Thus when everything finally spirals out of control, the true horror of the situation is that there doesn’t seem to be any way in which the catastrophe might have been averted. It is impossible to abide what Bernard has been doing to the irradiated children for the last nine years, but equally impossible to deny the monstrous logic by which he and his colleagues have arrived at their scheme. After all, the one fact that would invalidate Bernard’s central premise— that the whole Soviet system was in truth one vast Potemkin village, with the Warsaw Pact’s apparently immense military might unsupported by any commensurate economic or technological infrastructure— was unknown in the West in 1961, and indeed would not even begin to be suspected until well into the 1970’s.

Joseph Losey was unusually well placed to make a movie about the all-consuming madness of the Cold War, for he had been on the receiving end of some of it himself. His career in Hollywood was derailed when it was only just getting started, for the House Un-American Activities Committee (and never has a government body chosen a more unwittingly apt name for itself than that) had some questions to ask him about a few of his friends. Unwilling to cooperate with J. Parnell Thomas’s reprehensible official witch-hunt, but recognizing well enough which way the wind was blowing, Losey fled to England to start anew; most of the films he directed during the 1950’s were made under various pseudonyms. The hysteria had cooled substantially by the turn of the 60’s, of course, and These Are the Damned carried Losey’s real name, even in American release. Given Losey’s history, it is all the more remarkable that this movie plays less as a simple indictment of Cold-War excesses than as a cry of desperation over the seeming impossibility of averting them. Perhaps someone who fits more comfortably into one of the standard right-wing/left-wing pigeonholes than I do would read it differently, but I can’t imagine it’s an accident that King, the only character in the film who is portrayed as being personally villainous, ends up allied in spite of himself to both Simon and the children, while the reasonable, compassionate, and utterly well-intentioned Dr. Bernard eventually commits the movie’s most shockingly evil deed.

Now let’s talk about King for just a bit. His inclusion here is probably the most curious feature of These Are the Damned. In one sense, King is a mere plot device, an instrument for herding Simon and Joan in the direction of the lab and the children, but he is also easily the movie’s most complicated character. First off, he’s one of the better B-movie psychos of the 1960’s, and an extremely effective vehicle for Oliver Reed’s tensely threatening screen presence. So fearsome is Reed, in fact, that the clownishness of the other rockers and the groan-inducing theme song with which the gang has been saddled (You remember Hammer’s embarrassing bid for hippy appeal in the last couple of Dracula movies? Well, this is much worse.) are unable to diminish him. King could just as well have figured in something from Hammer’s contemporary cycle of “mini-Hitchcocks,” and an unsuspecting viewer is likely at first to take These Are the Damned to be the studio’s answer to The Sadist. But more importantly, King muddies the waters like nothing else does during the final act. He may be meaner and crazier than practically anybody else in the whole Hammer canon, but his ferocity is the only thing giving Simon’s plan to escape from the bunker with the children the slightest prayer of success. I can’t think of any other film save maybe Cronenberg’s version of The Fly that pins so much of the protagonists’ hopes upon the valor and competence of the bad guy.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact