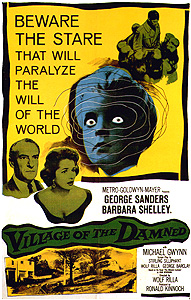

Village of the Damned (1960) ****

Village of the Damned (1960) ****

The original Village of the Damned, derived from John Wyndhamís novel, The Midwich Cuckoos, is another one of those movies with a storied reputation that doesnít get much attention these days because everybody but a couple of niche-market cable channels is afraid to air anything in that was shot in black and white. This is a crying shame, too, because itís probably the best non-Hammer British sci-fi or horror film of the 1960ís. At first glance, youíd probably figure it for your basic evil child flick, and it certainly does tread a lot of ground familiar from such movies. But even there, in the horror genreís classiest neighborhood, Village of the Damned has an intriguing feature to distinguish it from its peers. The children in it are dangerous, destructive, and even deadly, but because we never do learn just what their agenda really is, itís impossible to say with any certainty whether they are really evil or merely defending themselves with excessive vigor.

The movie starts of with a scene of bucolic tranquility so picturesque that at first I was afraid I had taped something else by mistake. In the little rural hamlet of Midwich, everything is following its usual, timeworn routine. Farmers are firing up their tractors, shopkeepers are setting their stores in order, and a scientist named Gordon Zellaby (George Sanders, from The House of the Seven Gables and The Picture of Dorian Gray) has just picked up the phone to call his brother-in-law, Major Alan Bernard (Michael Gwynn, from Scars of Dracula and The Revenge of Frankenstein), when an exceedingly odd thing happens. At exactly the same moment, literally every living thing in Midwich loses consciousness. It takes some time for anyone outside the village to suspect anything out of the ordinaryó interruptions in telephone service to isolated country settlements arenít exactly a rare occurrence, after alló but something about the way in which Bernardís conversation with Zellaby was interrupted gives the soldier a bad feeling. And because he had already been scheduled to oversee the training maneuvers of a battalion stationed not far from Midwich, Bernard gets permission from his commanding officer, General Leighton (John Phillips, of Torture Garden and The Mummyís Shroud), to embark early so as to check the place out beforehand. Needless to say, Bernard isnít expecting the sight that confronts him upon his arrival in Midwich. It isnít just that everyone in town is unconscious; anybody who goes beyond a certain point in the direction of the village is laid low, but there is no evidence of gas, radiation, or anything else that might cause such a phenomenon. The perimeter of the effect is so sharply defined that one step in either direction makes all the difference in the world, and stranger still, if an unconscious person is pulled back out of the affected area, they will snap right out of it with no apparent symptoms beyond a lingering bodily chill.

The military surrounds Midwich the moment word from the field gets back to headquarters, and immediately starts looking for answers. But before village physician Dr. Willers (Laurence Naismith, from The Valley of Gwangi and Jason and the Argonauts)ó who was serendipitously out on a house call when the plague of unconsciousness hitó can make any real headway toward figuring out whatís going on, the people of Midwich start waking up just as suddenly as they had passed out in the first place. All told, the whole strange situation lasted for about five hours; a subsequent study conducted by Doctors Zellaby and Willers fails to turn up even a hint of an explanation.

Midwichís brush with the abnormal has only just begun, however. When Zellabyís wife, Anthea (Barbara Shelley, from Cat Girl and Five Million Years to Earth, the UKís premier 60ís scream queen), announces that sheís pregnant, it seems at first like a dream come true. Gordon, some 25 years his wifeís senior, is not a young man, and the Zellabys had pretty much given up hope of ever having children. The funny thing is, though, that it isnít just Anthea. Every single woman of childbearing age in Midwich is knocked up tooó even a quartet of teenage virgins! In every case, the Midwich womenís fetuses are developing at a nearly impossible rate, and the births begin a good deal less than the usual nine months later. And when the kids are born, all of them are startlingly similar in appearance.

Itís a bit more than a year after that when the childrenís parents start noticing that thereís more weird about them than their identical blonde hair and piercing brown eyes. Their accelerated development continues, and at a time when most infants are just making their first serious efforts at walking or talking, Gordon and Antheaís son, David (whoíll be played by Martin Stephens, of The Innocents and The Devilís Own, once heís grown a bit more), is already spelling his own name and solving intricate spatial puzzles. Not only that, all twelve of the children born in the aftermath of Midwichís unexplained collective fainting spell seem to be linked telepathically to one anotheró if you teach one of them something, they all know it. Soon after that, the kids begin demonstrating powers of mental domination; David makes his mother scald her own hand in a pot of boiling water one day when she gives him a bottle of milk thatís been heated up too much. Before long, all of Midwich is in a state of low-level paranoia about the peculiar children, enough so that it draws the attention of the government and the military establishment.

Interestingly enough, Midwich isnít the only place where something like this is going on. Two towns in the Soviet Union, a tiny Eskimo settlement in Canadaís Northwest Territory, and remote villages in both China and Africa had their own broods of blond, brown-eyed psychics, but everywhere but Midwich and one of the Russian hamlets, the superstitions of the locals led almost immediately to the childrenís extermination. The Russians, being the Russians, collected all their remaining superkids and stuck them in a special school where their unique talents could be honed and perfected, presumably for eventual use in the service of the military or the KGB. A few months later, though, the Red Army destroyed the town where that school was located with nuclear weapons. And as the stories regarding David and his peersí powers and their disruptive effects on life in Midwich multiply, General Leighton and his civilian bosses start thinking more and more seriously that the Kremlin has the right idea for once. It isnít just that the children are phenomenally intelligent and possess superhuman powers, but that their apparent complete lack of emotion seems to make it impossible to fit them into society or indoctrinate them with any sort of community moral precepts. The kids do more or less what most human children their age would do if they had such abilities: use them to get whatever they want, whenever they want it, and to strike back at those who torment them or get in their way.

This is where the most interesting elements of the movieís script come into play. David and his fellow children turn Midwich completely upside down from the moment of their conception. At first, the husbands, boyfriends, and fathers of most of the pregnant women jump to the understandable conclusion that the women have been screwing around behind their backs. Some of the men were out of town when the children were conceived; others have been getting laid rarely enough that a pregnancy seems highly unlikely; in still other cases, there wasnít supposed to be a man in the pregnant womanís life at all. And for their parts, just about all the women except for Antheaó and this goes double for the four teen virginsó arenít exactly happy to have an unexplained, seemingly impossible pregnancy on their hands, either. In short, the people of Midwich have a grudge against the strange children even before they have a chance to demonstrate that they arenít quite human. After the psychic powers and supra-genius intelligence begin manifesting themselves, Gordon and Anthea Zellaby are just about the only people in the village who arenít ready to run the kids out of town on a rail. So when David and his compatriots turn violent, it isnít at all clear that we can blame them. The only difference, really, between these kids and any other childhood outcast is that you and I didnít have the power to force our tormentors to shoot themselves in the face with a shotgun. I donít know about you, but if I had... yeahó chances are Iíd have used it, even if only one time and in the heat of the moment. And because neither Gordon Zellaby nor anyone else ever succeeds in figuring out wható if anyó secret agenda the Midwich children are harboring, the audience has nothing more to go on in assessing the nature and degree of the threat they pose than do the adult characters in the movie. In essence, Village of the Damned forces you to choose between siding with a bunch of occasionally murderous, emotionless kids who may really be the vanguard of an invasion from outer space on the one hand, or hating and fearing those same kids for no very good reason but that they arenít like us on the otheró remember, everything bad that David and company do is either the product of a toddlerís temper tantrum or an act of admittedly overboard self-defense. Itís the kind of morally problematic situation that sends most American filmmakers running for the hills, and itís dealt with here in a completely unflinching and ultimately quite realistic manner. It may be a cliche, but itís also the truth: they really donít make them like this anymore.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact