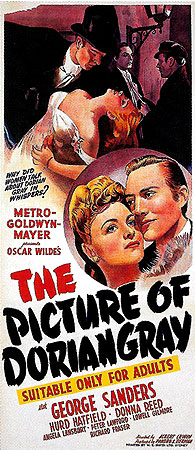

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) **

The Picture of Dorian Gray (1945) **

Oscar Wilde’s famous novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray, was another one of those works that seemed to get made into a movie at least once every couple of weeks during the silent era. Considering the sheer number of silent versions there were, it’s a bit surprising to see that no talkie version was attempted until 1945, when the second big Hollywood horror boom was already on its last legs. But in light of the way MGM’s The Picture of Dorian Gray came out, my inclination is to say that they ought not to have bothered in the first place.

Perhaps when the studio heads told him they wanted to do a talkie Dorian Gray movie, director Albert Lewin thought they had asked him for a talky version instead. In any event, that’s certainly what he gave them! Admittedly, Wilde’s novel isn’t exactly action-packed, concerning itself more with the philosophical dimensions of its story, but this movie is absolutely consumptive. On the other hand, it is at least relatively faithful to its source material. (In fact, I think it’s a bit too faithful for its own good— more on that later.) We begin with Lord Henry Wotton (George Sanders, who would go on to appear in Psychomania and the original Village of the Damned) taking a carriage ride out to the home of his friend, Basil Hallward (Lowell Gilmore). It’s difficult to grasp what these two men see in each other. Hallward is a man of fairly conventional ideas about life and how it should be lived, while Wotton is that most annoying species of bohemian, the sort who seems to choose his opinions solely on the basis of their power to shock the genteel sensibilities of his neighbors, and who prefers to speak in epigrams whenever possible. Perhaps Wotton likes Hallward for his artistic talents; the later man is a painter of no mean skill. And in fact, when Wotton arrives at his destination, he finds his friend setting up his easel in preparation for work on an especially striking portrait which he has very nearly completed. Wotton wants to know who the young man portrayed in the painting is, and Hallward reluctantly tells him his subject’s name is Dorian Gray. Hallward absolutely refuses to introduce Wotton to Dorian, however, on the grounds that the latter man is young and impressionable, and an acquaintance with Lord Henry could only have a bad influence upon him.

But circumstance has other plans, and Dorian (The Boston Strangler’s Hurd Hatfield) arrives at that very moment to begin his last sitting with Hallward. And sure enough, as Hallward paints, his friend fills the youth’s head with precisely the sort of hedonistic nonsense that the artist feared. Wotton’s ideas about youth (it’s “the only thing in the world worth having”) especially seem to strike a chord in Dorian, and by the time Hallward is finished, Gray has internalized Wotton’s thinking to such an extent that he idly makes a wish that Hallward’s uncannily lifelike portrait could be the one to shoulder the burden of the years instead of him.

A word of advice: before you go making wishes, look around and make sure that there aren’t any statuettes depicting “one of the 73 great gods of Egypt” lying about. Otherwise, you might just get what you wish for, and we all know what a drag that usually turns out to be. Hallward, you see, has just such a sculpture sitting on a table in his parlor, situated in such a way that its basalt eyes are staring straight at the painting when Dorian makes his wish. And as we shall soon see, Dorian Gray is about to become famous for (among other things) his remarkably well-preserved youth.

But all that is some years (and several scenes) in the future. Before we get to that, we must first establish what else is going to show up in the painting, rather than on the face that would be its natural home. The seeds of hedonism planted by Lord Henry send up their first shoots when Dorian begins frequenting a nightclub in one of the seedier parts of London. It is here that he meets, and is instantly smitten by, a pretty young singer named Sybil Vane (Angela Lansbury, who appeared many years later in The Company of Wolves and as a voice-actress in The Last Unicorn). Sybil, for her part, is equally taken with Dorian, and the two of them make plans to marry, despite howls of disapproval from all quarters. Dorian’s friends are scandalized that he would take a wife so far down the social ladder from him (except for Wotton, of course, who opposes marriage on principle); Sybil’s brother, James (Richard Fraser, from White Pongo and Bedlam), thinks Dorian just sees her as a fine piece of ass, to be used and discarded when she becomes inconvenient or tiresome. But it’s Wotton who ultimately gets everybody into trouble; he again has some advice for Dorian, and against his better judgment, his young protege ends up taking it. Wotton’s bright idea is that Dorian shouldn’t marry Sybil unless and until he is certain she is as virtuous as she appears on the surface. To that end, he advises Dorian to take her back to his place on some pretext or other— Hallward’s portrait will do nicely— and then protest when she decides it’s time for her to go home. If the girl still wants to leave, Dorian should turn the headgames up a notch, and make a big show of withdrawing his affection. Then, if she still insists on leaving, Dorian will know that he has indeed found a woman of outstanding purity, whom he can marry safely. You know what’s coming. Sybil is a good-hearted girl, but she lacks the willpower to stand on principle when it looks like her relationship with Dorian is at stake. The next day, Dorian, disgusted at Sybil’s weakness in the face of his own treachery, sends her a letter saying he never wants to see her again. The day after that, the heartbroken singer swallows poison and dies. Well, one certainly hopes that will teach Mr. Gray not to be such a gaping asshole in the future.

Of course, if it had, this would be one short-ass movie, and since this is MGM and not Universal we’re dealing with here, such things clearly cannot be. As a matter of fact, Sybil’s death convinces Dorian that there’s absolutely no point in trying to be good. He derives this somewhat counterintuitive notion from the fact that he learned of the girl’s suicide mere moments after deciding to return to her and beg forgiveness for his inexcusably shitty behavior. And at just about the same time that he learns he has Sybil’s blood on his hands, he notices something funny about Hallward’s portrait of him. The expression on his face has changed just slightly— a faint sneer has crept into his lips, giving him a hard, almost dangerous look. This is Dorian’s first hint that his earlier wish has come true, that the painting will henceforth become the repository for all the corrupting effects of age and debauchery. And so debauch Dorian does (off-camera of course— this is 1945, you realize), until, years later, a nimbus of sordid rumor surrounds him, sharply dividing his acquaintances into those who believe the stories, and those who believe the innocence written on his preternaturally youthful face.

One of the very few iniquities we are allowed to see Dorian commit involves his old friend, Hallward. The painter has plans to move to Paris, and before he goes, he wants to take one last stab at setting Dorian straight. It almost works. Though he of course does not go into detail (I remind you again of the date), Gray does confess that the nasty rumors circulating about him are true, in essence if not necessarily in their particulars. Hallward doubts him at first, but when he remarks offhand that no man can see another’s soul, Dorian realizes that he’s got something upstairs in his attic that will surely convince his friend. Though Hallward may be right as far as most people are concerned, Dorian’s soul is perfectly visible to those who know what to look for, for upstairs, in a locked room just beneath the eaves of his mansion, Hallward’s portrait lies concealed behind a drop cloth, so that no one but the sinner himself might see the incriminating evidence it depicts. The scene in which Dorian brings his friend up to have a look— and in which we finally see for ourselves what changes a life of unspecified depravity has wrought on the painting— is one of the truly great horror movie moments of the 40’s. But once Hallward has seen the proof with his own eyes, Dorian gets second thoughts about the wisdom of his “confession,” and in a mad panic to protect his secret, he murders his friend, and then watches with renewed horror as the hands of his oil-and-varnish alter-ego turn red with Hallward’s spilled blood. Next, Gray compounds his crime further by blackmailing another old friend, a scientist of apparently questionable professional ethics by the name of Allen Campbell (Douglas Walton, who had played Percy Shelley in the prologue to Bride of Frankenstein), to dispose of the body. Worse yet, Campbell kills himself in remorse shortly thereafter.

So with all this going on, it can’t be a good thing when Dorian sets his romantic sights on Hallward’s young niece, Gladys (Donna Reed— yes, the Donna Reed!). Gladys has had a crush on Dorian since she was a little girl, and even though that was 20 years ago, the man’s stubborn refusal to age like the rest of us has kept him fresh enough to remain desirable to a woman young enough to be his daughter. With their attraction thus established as mutual, it’s only natural that neither Dorian nor Gladys sees the fact that she already has a boyfriend (his name is David Stone, and he’s played by Peter Lawford) as much of a problem. What unquestionably is a problem, though, is the reentry into the plot of Sybil’s brother, James. You remember James— he was the guy who didn’t want Sybil seeing Dorian, on the grounds that he would only hurt her. Yeah, well evidently, James has spent the last 20 years or so tracking Sybil’s “Sir Tristan” down, and it’s at this point in the movie that he finally catches up with him.

But don’t you go fooling yourself. This movie isn’t over yet. James is gunned down in a hunting accident while trying to ambush Dorian, and so he will not be available to serve as our climax-inducing plot device, except in the most indirect manner. All he is able to do is give Dorian a sudden attack of conscience, leading ultimately to the ageless degenerate’s decision to destroy Hallward’s accursed painting, and take whatever consequences may come to him. I’m sure you have some idea of what those consequences might be, so I needn’t tell you what Gladys, David, and Lord Henry find when a chain of chance meetings brings them together with the intention of stopping by Dorian’s place and figuring out once and for all exactly what his deal is.

Ladies and gentlemen, the name of your enemy is Boredom. The Picture of Dorian Gray certainly isn’t all bad (it’s got that fantastic unveiling scene— shot in Technicolor for added effect!), but it suffers tremendously from the effects of mid-40’s prudishness. Having pondered the issue at length, I think the last chance for a really good, really faithful Dorian Gray movie came in 1934, just before the industry-wide agreement on the part of studio heads to relinquish their appellate authority over the Production Code Administration finally gave the Hays Code some real teeth. Under the PCA’s rules, The Picture of Dorian Gray’s creators weren’t even allowed to talk about all the dirty things Dorian does to amuse himself. True, Wilde’s novel is just as elliptical, as it had to be given the cultural climate of Victorian England, but there are some things you can get away with on the printed page that are simply unacceptable in a visual medium like film. With no authority to depict or even to describe Gray’s sins, the filmmakers had no other option but to rely heavily on voice-over narration. In fact, if you ask me, narrator Sir Cedric Hardwicke (who also narrated War of the Worlds), though completely uncredited, ought to have received top billing— God knows he gets more “screen time” than any of the real actors! The movie thus leaves you with the unpleasant feeling that you’d have been just as well served by listening to someone synopsize the novel. On the other hand, I don’t really think a post-Code Dorian Gray movie could have been much better (though one could certainly have been more fun). By the time the Code collapsed under the weight of its own irrelevancy in the early 1960’s, the public’s taste for, and indeed expectation of, increasingly explicit portrayals of formerly taboo material made it just about impossible to tell this story in anything like a restrained and tasteful manner. And in fact, when this movie was remade as The Secret of Dorian Gray in the early 70’s, the new creative team was so utterly unbridled in their depiction of the title character’s squalid lifestyle that this remake has become nearly legendary in the world of exploitation cinema. Now it’s a rare day indeed when I, of all people, come out in favor of taste and restraint, but in this case, I think the character of the source material demands it. But restraint isn’t the same thing as a straitjacket, and unfortunately, a straitjacket is exactly what the mid-40’s censorship regime imposed on The Picture of Dorian Gray.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact