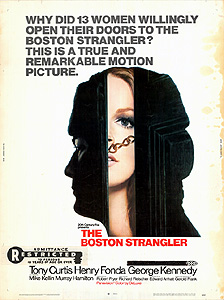

The Boston Strangler (1968) ****

The Boston Strangler (1968) ****

I don’t normally care too much for cop movies, but every once in a while, I’ll run across one that is so well made (like, say, Dirty Harry), so unusual in its handling (Seven, perhaps), or both (The Silence of the Lambs, anyone?) that it overcomes my usual lack of interest in the police procedural as a genre. To be sure, the very occasional utter stinker will catch my eye, too (don’t be surprised if you see a review of Cobra turning up here one of these days), but mainly it’s the exceptionally good and the totally original that gets my attention in movies where the main characters are waving badges around. 1968’s The Boston Strangler is one of those doubly rare cop-centered mystery flicks that gets me on both counts, and like the majority of the police procedurals that I have particularly enjoyed, it has at least the larva of a horror film squirming around inside its guts somewhere.

Oh, yeah— and it’s based on a true story. I know very little about the real Boston Strangler case (despite my rather morbid overall sensibility, I’ve never been one of those people who makes a hobby out of studying the case histories of serial killers), beyond that Albert DeSalvo, the man who confessed to the crimes, spent the rest of his days in a mental hospital. I’m also dimly aware that DeSalvo’s killing spree was huge news at the time, even outside of Massachusetts, where people would be expected to take a special interest in it. In general, though, I don’t have the background that would be necessary for me to judge how closely The Boston Strangler follows the facts of the case, so I’ll basically be treating this as just another movie. Hollywood being what it is, that seems the safest way to go.

The plot here is very, very simple. There’s somebody running around Boston, strangling and sexually assaulting women. The killer’s early victims are all elderly ladies who lived alone, and because all have been slain in their homes with little indication of housebreaking, it would seem that the murderer prefers to talk his way through his victims’ front doors whenever possible. The Strangler is very careful, though, and leaves no evidence behind that might be used to trace him— no fingerprints, no semen, nothing. His only calling card is the ligature bruises he leaves on his victims’ throats, supplemented occasionally by narrow, cylindrical objects jammed into their vaginas and savage bite marks elsewhere on their bodies.

The Strangler is also smart enough to move around; his attacks have taken place in several different jurisdictions, adding bureaucratic hurdles to the obstacle course the police will have to run in order to catch him. And as the body count rises, and the Strangler widens his net to include victims of all ages, races, and social strata, panic starts sinking its claws into Boston and its kindred communities. Phil DiNatale (George Kennedy, from Death Ship and all those impossibly stupid Airport movies), the detective in charge of the downtown side of the investigation, begins running in sex offenders of all stripes out of sheer desperation— the cops even start pestering homosexuals, despite the obviously heterosexual nature of the crimes. When even this looks likely to fail, District Attorney Edward W. Brook (William Marshall, from Blacula and Abby) establishes a special bureau expressly for dealing with the Strangler Case, placing his criminologist friend, John S. Bottomly (Henry Fonda, whom most people remember for movies more tasteful than Tentacles or The Swarm), in charge of it. The idea here is that this bureau will have access to all of the evidence gathered by all the separate police departments working the case, and will wield the authority to overcome such petty squabbles over bureaucratic turf as so often hamper crime-solving efforts involving more than one jurisdiction. But as the number of victims climbs into the double digits, Bottomly, DiNatale, and their colleagues still have nothing to show for their work but a city full of harassed homosexuals, frightened foot-fetishists, and paranoid peeping Toms.

Meanwhile, we in the audience have been spending some time with a working-class family man named Albert DeSalvo (The Manitou’s Tony Curtis). DeSalvo doesn’t seem quite normal— sort of withdrawn and distant, maybe even from himself. And with rapidly increasing frequency, he takes long lunches at work to pay lethal visits to the homes of women he doesn’t know. But because the police are busy chasing queers and flashers, DeSalvo isn’t even on their radar. One day, however, DeSalvo gets sloppy, and one of his victims escapes, biting him on the hand while she does so. Bottomly and DiNatale naturally spend a lot of time with her in the ensuing days, though she remembers almost nothing of her encounter with the Strangler. Then a bit later, DeSalvo picks the wrong apartment to break into, and finds it occupied by a fit, young man instead of the woman he thought he saw enter it a moment before. DeSalvo is quick to make a break for it, but the man in the apartment pursues him out into the street, and the chase eventually leads them past a pair of police cruisers. Thus, in a scene that rings so true it must have been taken from the real course of events, the Boston Strangler is picked up for breaking and entering, and the cops don’t even realize they’ve got him! The identification is later made through sheer luck, when Bottomly and DiNatale just happen to find themselves sharing an elevator with DeSalvo and one of his captors after interviewing the killer’s most recent intended victim, and the two men notice that the wound on DeSalvo’s hand matches perfectly with the escaped girl’s story.

The best part of The Boston Strangler isn’t the tale of the investigation, though. While often gripping, and directed with a visual flair that is almost completely unheard-of in movies of this sort, the hunt for the killer takes a back seat to what follows it, as Bottomly interrogates DeSlavo, and discovers that the man honestly doesn’t realize he’s a notorious killer. DeSalvo, you see, suffers from multiple personality disorder; in a sense, he really isn’t the Strangler at all! But as he spends more and more time talking with the criminologist-turned-detective, DeSalvo begins stumbling upon his alter-ego’s memories, and comes face to face with the terrible secret he’s been hiding even from himself. The interplay between Henry Fonda and Tony Curtis in this final phase of the movie is breathtaking. Curtis especially distinguishes himself with his fully believable handling of some very difficult scenes; contrary to what might be expected, Curtis’s acting becomes more underplayed the more deeply in touch DeSalvo comes with the murderer inside him, until the final shot leaves him staring with silent introspection at his own monstrousness. In the end, DeSalvo comes to seem worthy more of our pity than of our fear or revulsion, and it comes almost as a relief to realize that D.A. Brook and his staff will never be able to convict him with no solid physical or eyewitness evidence, and nothing to bring to a trial but the confession of an obviously insane man. Bottomly’s statement that DeSalvo’s inevitable lifelong commitment to an asylum is “the next best thing to a conviction” misses the mark; given the strange circumstances of the case, justice is really better served this way.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact