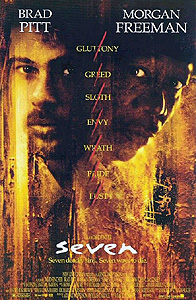

Seven/Se7en (1995) ****

Seven/Se7en (1995) ****

I don’t know why it took me so long to notice this. You know all those horror movies you see today that manage to look both slick and gritty at the same time, as if their producers had hired armies of set-dressers to hand-polish the grits individually? Movies like Alexandre Aja’s The Hills Have Eyes or Marcus Nispel’s The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (and its sequel even more so)? They’re all just copying and exaggerating the visual esthetic of Seven. When I first saw Seven upon its initial release, what immediately struck me about it was that I had never seen a big-budget film look so grotty before, or give so strong an impression that it went out of its way to do so. The big difference between this picture and its imitators is that director David Fincher seems to have had a conscious purpose behind Seven’s stylized ugliness. It is a film in which heroes and villain alike view the world they live in as a corrupt and corrupting place, a virulent scumpit of moral and physical misery. The movie looks the way it does because that’s how its characters feel about their lives, rather than simply because somebody thinks meticulously crafted squalor is cool. At the time of its release, Seven was given maybe a little more credit than it really deserves. Its catechistically inspired murders have a pedigree stretching back at least to the early 1970’s, and a close examination exposes a much tighter adherence to the threadbare buddy-cop formula than seems consistent with the movie’s reputation for originality. Nevertheless, it’s still vastly smarter than most of the films that have followed its esthetic example in recent years. It offers near-perfect thematic consistency where many movies of its type don’t even bother to have a theme, it features some extremely classy acting from capable performers who have spent far too much of their careers slumming, and it has a memorably nasty ending that is impossible to fit into any of the conventional happy/sad, defeat/victory pigeonholes.

William Somerset (Morgan Freeman, from Kiss the Girls and Deep Impact) is a homicide detective in some rundown, scummy old city— or at any rate, he is for the next week. Somerset is burned out something fierce, and he has arranged to take early retirement. His last big assignment is supposed to be familiarizing his replacement, the recently relocated Detective David Mills (Brad Pitt, of Twelve Monkeys and Cutting Class), with the way things are done here in his town’s most evil precinct. In point of fact, however, Somerset’s final week on the force is going to be just a little more complicated than that. The morning after he and Mills first meet (and first knock heads, their interpersonal dynamic following the standard wise veteran/brash rookie cop-movie template), the two detectives are summoned to examine the dead body of the fattest motherfucker either of them has ever seen. With the mountainous corpse lying face-down in a bowl of pasta, Mills understandably assumes at first that he died of a heart attack while gorging himself, but then he and Somerset notice that the deceased’s hands and feet are tied. There’s also an ominous-looking bruise on the back of the dead man’s head. It isn’t until the medical examiner has a look at the body that it becomes officially the homicide squad’s problem, though— evidently, some sick fuck held a gun to the guy’s head, and made him eat until his stomach ruptured and he bled to death internally! Somerset wants no part of the case, and not just because it’s exactly the sort of extreme bummer that’s leading him to hand in his badge in the first place. Mills and the captain (R. Lee Ermey, from the remakes of Willard and The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) may scoff, but the old detective is convinced that this is only the beginning of a monstrous and potentially lengthy murder spree, and that’s more than he feels himself capable of handling on his way out the door. Understandably, the captain doesn’t much care what Somerset does or does not believe he can handle.

Somerset, as you might expect, is the only one who is not surprised the next day, when big-shot defense attorney Eli Gould turns up dead in his office, his bled-out body flanked by a scale containing exactly one pound of flesh sawn from his torso on one side and the word “GREED” spelled out in gore across the carpet on the other. The police department and District Attorney Martin Talbot (Richard Roundtree, of Amityville: A New Generation and Shaft) alike initially treat Gould’s death as a separate, unrelated case, but Somerset has a hunch. Looking over the fat man’s apartment a second time, he finds the word “GLUTTONY” written on the wall in grease behind the refrigerator. His colleagues are dismayed to say the least when Somerset informs them that they can expect a minimum of five more baroquely hideous murders before the perpetrator finds something else to do with his time: one each for Sloth, Lust, Pride, Envy, and Wrath. Equally dismaying for the proudly uneducated Mills is the prospect of having to read Paradise Lost, the Divine Comedy, and the Canterbury Tales for insight into the killer’s thinking. And Mills’s wife, Tracy (Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow’s Gwyneth Paltrow), is maybe more dismayed than anyone once she learns what her husband is working on. She hadn’t wanted to move to the city in the first place, for precisely the reason that this sort of shit happens there. Being newly pregnant doesn’t put any cheerier a face on the situation for her, either.

There are no fingerprints, hairs, or fibers at either of the crime scenes that cannot be accounted for by the victims, so Somerset and Mills go to interview Gould’s widow (Psycho Cop’s Julie Araskog) in the hope that she can spot something out of place in the photos of her husband’s office. There is one thing— the abstract painting on one of the walls has been turned upside down. No clues turn up on the painting itself, but Somerset finds palm- and fingerprints on the wall behind it. They’re not Gould’s, and they’re arranged so as to form the phrase, “HELP ME.” Does this mean the killer is trying to stop? That question may be of academic interest only, because the prints match a set in the department’s records. They belong to a man named Victor, who has a long history of drug-related offenses; on the surface, it wouldn’t be altogether surprising for a wastoid like him to have a psychotic meltdown one day, but Somerset thinks the killer has thus far displayed too much purpose for that. Indeed, when he, Mills, and the SWAT team arrive at Victor’s junkie crash-pad, they discover that he is not the killer, but another one of his victims, the prints in Gould’s office having been planted with his severed left hand. The already slothful Victor has spent the whole of the past year strapped down to his bed, given enough food and water to keep him just barely alive and enough of his favorite drugs to make sure he stays just barely conscious. By now, he’s a bedsore-ridden vegetable, and the doctors who treat him at the hospital openly say that it would be the best thing for him now if he could die peacefully in his sleep. Somebody’s been keeping the rent paid on time, so the landlord never even noticed.

That puts the investigators back at square one, with nothing but the theme of the crimes to guide them. Somerset decides to bend the rules a bit. He has a contact in the FBI, who is just dirty enough to sell information from the database the Bureau keeps on the reading habits of people who check out certain sensitive materials (Mein Kampf, say, or The Anarchist’s Cookbook) from the nation’s public libraries. A bit of Mills’s money gets them the address of a man by the unlikely name of John Doe, who has recently been on exactly the sort of Seven Deadly Sins binge that Somerset is looking for. Doe (Kevin Spacey) comes home from an errand of some kind just in time to see the two cops hanging out in in front of his apartment, and what Somerset envisioned as an informal interview (it would have to be informal, since the tip that led him to Doe was illegal) turns into a running gun-battle through two or three apartment blocks and their adjoining alleys, very nearly getting Mills killed. Now that they know pretty much for sure that Doe is their man, Mills trumps up an excuse to search his flat, which turns out to be several hundred square feet of concentrated pious insanity. The only really useful thing they find, though, is a photograph of the prostitute whom Doe seems to have selected for his dramatization of the sin of Lust. Even that victory has a distinctly pyrrhic cast to it, for Doe now picks up his pace, and the police are too late to save the hooker from being fucked to death with the world’s most blatantly lethal strap-on. (“I thought he was a performance artist!” protests the leatherwork specialist who constructed the instrument when Mills and Somerset question him.)

Pride comes next. This time, John Doe has imprisoned a beautiful and presumably extremely vain woman in an apartment much plusher than any of the other dwellings we’ve seen in the movie so far. He’s cut off her face, bandaged her up nice and tight so that she won’t bleed to death, and left her with a cell phone in one hand and a bottle of barbiturates in the other. He gave her a choice, you see— call 911 and survive to face the rest of her life horribly disfigured, or say “fuck it” and eat a bunch of pills. The fact that Doe picked this particular woman to illustrate the sin of Pride should tell you what her solution to the quandary was. That’s five out of seven sins accounted for, and the police still haven’t accomplished much beyond forcing the killer to exchange his home for an unknown bolt-hole somewhere in the city. Furthermore, it turns out that leatherworker was closer to the truth than anyone yet realizes. In an important sense, John Doe really is a performance artist, and it’s just about time for the audience-participation segment of the show to begin…

I tend to think of Seven as sort of a delayed response to The Silence of the Lambs. The phenomenal success of that movie can’t have been far from Bob Shaye’s mind when the Seven screenplay arrived at New Line Cinema’s offices, naturally, but that’s only a part of what I mean. Ever since Psycho— hell, maybe even ever since M— Hollywood’s maniac movies have devoted themselves to a constant search for a killer more impressive, more compelling than the last one. From Norman Bates to Leatherface to Michael Myers to Freddy Kruger, we see a constant escalation of weirdness— a new psychosis, a new weapon, a new ability, a new immunity, a new deformity. Let’s face it, though. Once you get to Anthony Hopkins as Hannibal Lecter, where the hell can you possibly go from there? Seven’s answer is to pull the plug on the whole enterprise of charismatic killer one-upmanship, giving us instead a murderer who goes out of his way to be a complete cypher, even to the extent of adopting the name “John Doe.” He’s short, bald, soft-spoken, and so totally ordinary and inconspicuous that he can walk into a room covered in the blood of three human beings without attracting any notice at all until he goes out of his way to draw attention to himself. This is no hulking, unstoppable death-machine, no sardonic quipster, no demonic genius. John Doe probably can’t so much as perform a single chin-up, but he, as he eventually points out himself, is not the important thing. What matters is his work, the trail of horrifically mangled corpses that Somerset and Mills follow from one unrelated locale to the next, and the grisly message that unifies all the murders. John Doe is trying to make a point, and nobody understands better than he does that his own personality is at best immaterial to that point and at worst a distraction from it. And so he does everything within his power to efface what little personality he has, vanishing into his grotesque project as completely as he can. It was probably not the sort of trick that can be played successfully a second time, so it shouldn’t surprise us much that Seven did not inspire a sustained withdrawal from the age-old pursuit of bigger and better maniacs. Nevertheless, the character of John Doe is maybe the best example of the care that Fincher and screenwriter Andrew Kevin Walker put into elevating Seven above the cliches it so often employs.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact