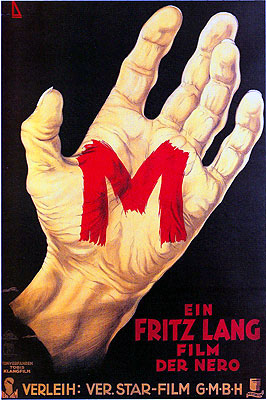

M / M: Eine Stadt Sucht einen Mörder / M: Mörder Unter Uns (1931) ***

M / M: Eine Stadt Sucht einen Mörder / M: Mörder Unter Uns (1931) ***

In the early days of cinema, the Germans were so far ahead of Hollywood it wasn’t even funny. I’ve touched on the staggering artistry of the Expressionist directors of the silent era already. Now, I’d like to turn your attention to an early German talkie, Fritz Lang’s much-vaunted M. This was actually Lang’s first talking picture, and though it does not tower above the competition in the way that, say, Murnau’s Nosferatu does, or match Lang’s earlier Metropolis for sheer spectacle, M is still an awfully impressive, if structurally flawed, film. So impressive, in fact, that it broke out beyond Germany’s borders to revitalize Lang’s international stardom, while bringing it for the first time to actor Peter Lorre.

The inspiration for this film was provided by the criminal career of Peter Kurten, the Dusseldorf Vampire. Kurten was a psychopathic serial killer who preyed on children, especially young girls, sexually assaulting them and sometimes even drinking their blood in addition to murdering them. He’d been killing off and on since 1913, but it wasn’t until 1929 that Kurten really hit his stride, touching off a nationwide panic in Germany. He was caught in May of 1930, after a sixteen-month reign of terror, but his trial and conviction did not come until early in 1931. A bit later that year, such fresh memories of real-life horror were more than enough to pack in the crowds for a movie premised on the activities of a Kurten-like killer, even if the plot of the film itself bore little resemblance to the actual course of events.

M drops the Kurten reference early. Amid the mutterings of adults scandalized by a series of grisly child killings, a gaggle of kids walk home from school. One of them, a little girl named Elsie, meets up with a man named Hans Beckert (Lorre, who would go on to appear in great numbers of American films, including a few horror flicks like Tales of Terror and The Beast With Five Fingers) along the way. Beckert talks her into following him for a while, buying her a large balloon animal from a blind bum (and whistling “In the Hall of the Mountain King” in a most disconcerting manner while he’s at it). The moment Beckert gets Elsie out of the view of passers by, he slays the girl and flees to his home.

According to the newspapers that begin circulating the next day, Elsie’s was the eighth such murder to be committed in town recently. (The real Kurten would confess to nine murders, seven attempted murders, and rapes, arsons, and batteries almost beyond counting.) The townspeople begin panicking, accusing each other of the killings on the slightest pretext, and besieging the police department with calls purporting to identify the murderer. All of these “tips,” naturally, are little more than the paranoid ravings of the terrorized and high-strung, and are of no value whatsoever to the police who are, nevertheless, obliged to follow them up— to the incalculable disgust of those on the receiving end of the ensuing investigations. In desperation, Inspector Karl Lohmann (Otto Wernicke, from The Testament of Dr. Mabuse and The Man from Another Star), the detective in charge of the case, begins targeting the criminal underworld, sending an army of cops to roam the city’s sleaziest neighborhoods sniffing for any illegalities.

But as anyone with even a passing familiarity with serial killers and their psychology could tell you, your Al Capones and your Richard Specks generally conform to very different psychological profiles, and the hangouts of con men and mafiosi probably aren’t the most fruitful places to look for a pathological killer. On the other hand, Lohmann’s policy certainly cleans up the streets a bit, sending hookers and pimps and racketeers down to the precinct by the literal truckload. This is where mob boss Schraenker (Gustaf Grundgens, who would play the devil in the 1960 German film version of Faust) comes in. Schraenker has had it up to here with the killer, whose activities have put the entire city under the microscope of the police. With so many cops prowling around, it has become very difficult for career criminals of every type to ply their trades; in short, Beckert is bad for business, and Schraenker thinks it’s time something were done about him. What the godfather suggests is for all the gangs and syndicates in the city to team up for the sake of catching the child killer, laying aside whatever differences they may have over questions of territory or personal rivalries. Now obviously, it’s not going to be easy for the mob to set itself up as a parallel vigilante police force, certainly not with a legitimate cop on every third corner, but Schraenker has thought of a way around this problem. The mobs will employ every beggar, bum, and street person in town to act as their surveillance network; after all, no one will think twice about seeing a panhandler hanging out on the same block all damn day watching the crowds pass by.

In what is probably M’s most original plot twist (though we’ve of course seen much the same thing many times over the 70 years following its release), the mob finds Beckert before the police do, cornering him in the attic of an office building after a group of beggars interrupts him while he tries to set up his next victim. The gangsters capture their quarry, and take him to a warehouse basement for a sort of trial, the jury seemingly made up of every citizen in town with an income below 125% of the poverty line. Just as Beckert confesses to his crimes, in an impassioned speech in which he professes an innate inability to control his murderous impulses, Lohmann’s police burst in on the “court,” having been told by a captured gangster what Schraenker’s been up to. Beckert is thus spared the rough justice of the mob, though it’s difficult to imagine the legitimate penal system being much kinder to him. Kurten, after all, went to the guillotine.

M is hampered throughout by glacial pacing. Lang’s direction is fabulous, but his material is such that he needs every ounce of his talent to pull this film off. Such scenes as the opening pursuit and slaughter of Elsie and the later one in which the beggars foil Beckert’s attempt to isolate another victim are skillfully handled and impressively tense affairs, but there is simply too much dead weight in between for M to build up the momentum it needs to fulfill its potential. Furthermore, Lorre’s creepy murderer doesn’t get anywhere near enough screen time in the first half of the film, and he spends much of his time in the second hiding from gangsters in an attic. This, let us remember, is a man who has placed an entire city in the grip of fear; we ought to see more of him, so that we can share in some of that unease. Lorre’s fantastic performance in the trial scene just serves to make his underutilization seem that much more regrettable. But when M is working smoothly, it is a real pleasure to behold, especially when compared to the unimaginatively directed programming American studios were turning out at the time.

Another interesting point about M is its curious interaction with one of the major currents of 20th century history. Anybody remember what was going on in Germany in 1931? Good call. Yes, that would be Hitler’s accelerating rise to power. Fritz Lang and Peter Lorre were both Jews, and Germany in 1931 was already nearly as bad a place to be Jewish as it would famously become a couple of years later. Worse yet, the owner of the studio where M was filmed was also a Nazi party activist! (That studio owner is the main reason for the film’s enigmatic title— when Lang came to him with a movie called Murders Among Us, the moneyman assumed he was being asked to produce an anti-Nazi political film, and refused to have anything to do with the project!) Though the subject never explicitly comes up, the early scenes depicting the terror-stricken townspeople scapegoating each other on the flimsiest of excuses, often threatening actual physical violence, take on a powerful subtext when you look at M as a product of its time and place. Ironically, M actually ended up serving as pro-Nazi propaganda, as Lorre’s confession was appropriated by the makers of The Eternal Jew, perhaps the most vicious of the Goebbels-backed, wartime Holocaust apologist films.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact