The Beast with Five Fingers (1946) ***

The Beast with Five Fingers (1946) ***

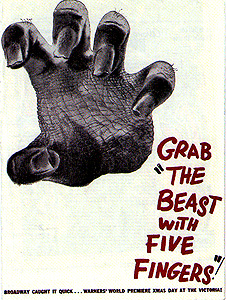

The Beast with Five Fingers hit the theaters, incongruously enough, on Christmas Day, 1946. After that, there would be only one serious horror film to see release in America until 1951, and The Beast with Five Fingers would be the last to deal even half-heartedly with the frankly supernatural until 1956. The amazing thing, considering how lasts of their kind usually turn out, is how high up in the right tail of the 40ís horror bell curve this movie is. Admittedly, it takes too long to get moving and it has the worst ending since The Ape Man, but it also has a long list of points in its favor.

The first of those points is the way screenwriter Curt Siodmak handles his character introductions. Within five minutes of meeting American expatriate Bruce Conrad (Robert Alda, from The Devilís Hand and The House of Exorcism) at a sidewalk cafe in the little Italian village of San Stefano, we know exactly the sort of person he is without ever having to force down the sort of glutinous bolus of exposition one expects from the average B-movie writer. Simply put, Bruce is a con-artist, but heís a lovable, cuddly con-artistó mostly harmless and so charming even the local commissario of police, Ovidio Casanio (J. Carrol Naish, of Jungle Woman and The Monster Maker), canít bring himself to do more about his activities than give him the occasional scolding. After all, heís only selling bogus antiques to rich American tourists. Conrad also has another source of income, the charity of an old friend of his from the Statesó pianist Francis Ingram (Victor Francen, from End of the World and the second JíAccuse!). Ingram lives in the villa overlooking San Stefano because his poor health (the right side of his body is paralyzed as the result of a stroke he suffered many months ago) demands peace and quiet, and the manís seemingly inordinate affection for Conrad stems at least in part from a tremendous favor Bruce once did for him. Conrad has a fair amount of musical talent himself, and after Ingram lost the use of his right hand, Bruce devised a cunning rearrangement of Bach that could be played one-handed by someone of Ingramís extraordinary dexterity, thereby saving the pianistís career in the event that the rest of his recuperation goes according to plan.

Ingram has to accept the possibility that it wonít, however, and with that in mind, he has decided to gather together the few friends he has in the world to serve as witnesses to his will. In addition to Bruce Conrad, those friends are his loyal but increasingly exasperated nurse, Julie Holden (Andrea King, from Red Planet Mars and House of the Black Death), his lawyer, Duprex (The Creeperís David Hoffman, who played the Spirit of the Inner Sanctum in the series of quickie thrillers based on the ďInner SanctumĒ radio show); and Hillary Cummins (Peter Lorre, of Mad Love and Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea), his secretary for the past twenty years. Actually, Ingramís trust in this bunch is somewhat misplaced. For one thing, anyone who reckons his lawyer a friend simply hasnít been paying attention. Julie, meanwhile, has lost almost all of her original affection for the pianist due to the stifling, possessive, controlling form that his own love for her takes. Indeed, Julie plans on leaving Ingramís service in the very near future, and has already applied for her exit visa. As for Hillary, his two decades of devotion have not been to Ingram but rather to his library. The secretary considers himself an occult scholar, and he has made much use of the vast collection of antique works on astrology that Ingramís Italian ancestors had amassed at the villa over the years. For Hillaryís purposes, his bossís stroke and subsequent infatuation with Julie have been a godsend, leaving him free to pursue his arcane efforts to reconstruct the body of ancient secrets that he believes was lost in the burning of the Alexandria library. It would also seem that thereís something just a trifle fishy about Ingramís will, because he makes a big show of making everyone present attest to the soundness of his mind before he has them sign on as witnesses.

Well whenever somebody in a horror movie makes a will, that characterís death cannot be far behind, and The Beast with Five Fingers falls right into line on this point. The night following the signing of the will is filled to overflowing with drama. Julie reveals to Bruce her intentions of leaving the villa, and he in turn reveals that he has fallen just as deeply in love with her as Ingram has. Hillary, spying on the pair from the other end of the garden, overhears all of it, and he informs his boss. This isnít so much because of any protective feeling toward the pianist (in fact, Hillary takes obvious sadistic pleasure in telling Francis that his beloved nurse plans on running away from him), but because Hillary wants to keep Julie around to monopolize Ingramís attention so that he can study the black arts in peace. Regardless of his motives, Hillary hasnít thought this confrontation out too thoroughly, because he is taken by surprise when Ingram flies into a rage and seizes him by the throat, accusing his secretary of lying in order to sabotage Ingramís ďbudding relationshipĒ with the nurse. And however feeble the rest of him has become, Ingramís left hand is fiendishly strong; Hillary nearly dies under that crushing grip before Julie fortuitously walks in on the scene and rescues him. Francis himself is not so lucky later, when he awakens in the middle of the night, finds Julie gone from her accustomed place at his bedside, and accidentally rolls his wheelchair down the stairs to his death when he goes looking for her.

Francis had no blood relatives, but he did have two cousins by marriage in the US. Raymond Arlington (Charles Dingle) is the archetypal Ugly American. When he and his son, Donald (John Alvin, seen later in The Legend of Lizzie Borden), arrive at the villa after Ingramís funeral, the first thing they do is to begin sizing the place up for how much money it and its contents (especially the ancient tomes of which Hillary is so covetous) are going to bring them, it apparently not having ever occurred to them that they might not be the sole beneficiaries of the pianistís will. Theyíre not. In fact, Ingram has gone and willed everything he owns to Julie! And despite Bruceís suggestion that she might not intend to accept the dead manís largesse (she was planning on leaving the country, you know), Julieó seemingly motivated at least partly by the instant loathing she understandably developed for the Arlingtonsó announces that she means to keep every penny. Needless to say, the Arlingtons immediately start making noises about contesting the will, and they secretly engage Duprex as their attorney in the matteró the latter man being more than happy to sell out his supposed friendís wishes in exchange for a third of the estate.

Yeah, I know what youíre thinking at this point. Youíre observing that there has yet been no mention of any beasts, with any number of fingers. Well thatís about to change. That night, several of the people staying at the villa notice a light on in the mausoleum where Ingram was interred. No one is there when the men of the house investigate, of course. But later on, after everyone has gone to bed, Duprex is murderedó strangled to death by someone with an inhumanly strong gripó while writing up the papers for fighting the will. Not only that, Julie, Bruce, Hillary, and the Arlingtons all hear Conradís Bach arrangement being played on Ingramís old piano (the keyboard to which has been locked up ever since its owner died), and the dead manís former secretary discovers his bossís garishly immense ring lying on top of the instrument, in exactly the place where Ingram used to set it down whenever he played. The death of Duprex gets Commissario Casanio involved, and everyone staying at the villa is ordered confined to it until such time as the case is solved. When Casanio leads an investigation of the mausoleum the next day, it comes to light that Ingramís coffin has been opened and his left hand severed, although there is no sign of anybody having entered the crypt. There is a broken window, but the hole in it is only about five by ten inches, and the glass was smashed from the inside. In the soft earth below that window, however, is a disturbing clue indeed: a single palm-print, followed by a trail of strange marks suggesting that Ingramís disembodied hand somehow crawled off in the direction of the villa of its own accord.

Really, The Beast with Five Fingers is more a murder mystery than anything else, and in the end, it marks a return to the annoying ďthere has to be a logical explanation!Ē sensibility that played so much havoc with American horror movies during the 20ís and early 30ís. And inevitably, when that logical explanation rears its head, the result plays like a depressing foreshadowing of ďScooby Doo, Where Are You?Ē, with the commissario revealing the arsenal of ridiculous, impossible contrivances whereby the culprit faked the activities of an undead hand. This in turn is followed by a coda that makes the fatal mistake of poking fun at everything weíve just seen, which is framed in such a way as to suggest that it was added on at the last minute in an effort to appease somebody with an expensive suit and a checkbook, who had argued from the beginning that there was something unseemly about making a movie about a crawling hand. Butó and itís this ďbutĒ that makes the movie worthwhile in spite of itselfó there is a nice, long stretch in the middle during which it seems just possible that the filmmakers will have the nerve to follow the killer hand premise all the way to its conclusion, and this section includes some of the finest, most skillfully realized scenes in any horror film of the 1940ís. Hilaryís struggles with the hand in the villaís library make for some amazing set-pieces, with crawling hand effects that have yet to be equaled in any other movie Iíve seen. And it is more than appropriate that Hillary should be the one to deal most directly with the handó Peter Lorre had a way with madness (and if you hadnít been mad to begin with, then squaring off against a living severed hand seems like the kind of thing that could put you there) that few other actors have ever been able to match. One naturally wants the second-to-last serious American horror movie of the 1940ís to be a good one, and for the most part, The Beast with Five Fingers is. Itís just too bad that the very qualities that give it its appeal also throw its most serious shortcomings into such sharp relief.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact