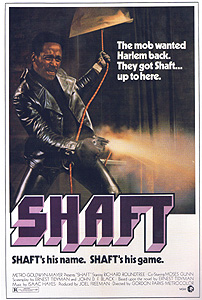

Shaft (1971) ****

Shaft (1971) ****

Now this is what you call mythmaking. The credits roll over a scene of a sleekly stylish black man striding purposefully down a Harlem street beneath grindhouse marquees advertising He and She and School for Sex, to the tune the strutting funk groove that transformed Isaac Hayes from an obscure Staxx Records songwriter into a soul music star in his own right. Heedless of oncoming traffic, the man forges ahead into a crosswalk in matter-of-fact defiance of the “Don’t walk” glaring at him from the opposing corner; when a taxi nearly runs him down, the man stops just long enough to give the driver the finger and bark, “Up yours!” Never in a million years would you guess that, in real life, Richard Roundtree was a child of the suburbs who once toured the country as a model in an Ebony magazine fashion show.

Shaft the movie is just as mythic— and often just as mythical— as Shaft the character. Almost universally credited with setting off the tremendous blaxploitation explosion of the early 1970’s, it has accrued a considerable amount of both praise and reproach that it doesn’t quite deserve, even as some of its very real merits and failings have gone mostly unmentioned. To begin with, as is so often the case, the celebrated first isn’t quite the first of its kind after all— not only was Melvin Van Peebles’s Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song so closely contemporary with Shaft that it’s difficult to be certain which really came first at this late remove, but the more famous film largely owes its existence to the unexpected success of Cotton Comes to Harlem the year before. Neither can it legitimately be claimed (as it so often is) that Shaft offered an unprecedented break to black actors and filmmakers— that door had first been wedged open in the middle of the preceding decade, and it would be better to say that Shaft’s contribution was to convince the studios that black moviegoers were a force to be reckoned with, economically speaking, and could deliver profitable box-office grosses for movies in which the larger white audience had little or no interest. Finally, the controversy that greeted Shaft’s release and the fawning of 30-odd years’ worth of blaxploitation fans have both missed what is almost certainly the most interesting point about this film, which is how non-exploitive it really is, especially in comparison to the literally hundreds of films that followed in its wake. More than just pride of place, Shaft has outlasted its imitators because its creators were at least as interested in filming a gripping crime drama in an update of the classic style as they were in cashing in on the emerging black market.

Seriously— make the main characters Irish or Italian rather than black, and Shaft would be nearly indistinguishable from an old Warner Brothers gangster picture. John Shaft (Roundtree, later of Q and Maniac Cop) is a private detective operating in the seedy concrete jungle of turn-of-the-70’s Harlem, a loner equally antagonistic toward official law enforcement and organized crime. Paradoxically, that dual outsider status makes Shaft immensely useful to both sides of the law, and few things could dramatize that more… well, dramatically than the chain of events that begins when Shaft stops by his favorite shoeshine parlor and is informed by the owner that a couple of armed men came by looking for him a while earlier. While he’s chewing on this piece of intelligence, Shaft bumps into his closest contact on the police force, Lieutenant Vic Androzzi (Charles Cioffi), together with his partner, Sergeant Tom Hannon (Lawrence Pressman, who can also be seen in the 1998 remake of Mighty Joe Young). The two cops know about the men on the hunt for Shaft, and they’ve also heard rumors that something big and ugly is about to go down in Harlem; proceeding from the reasonable assumption that Shaft’s network of local informants is better than anything he and his fellow policemen could come up with, Androzzi entreats the P.I. to come forward with whatever he knows. Shaft refuses (in a manner calculated to annoy the hell out of the uptight and mildly racist Hannon), but Androzzi knows he’ll have other opportunities to finesse the information out of him later.

Actually, the occasion comes that very afternoon. When Shaft reaches the building where he leases his office, he finds the gunmen he was warned about waiting for him, and a brief struggle ends with one of them tossed to his death from the window and the other sufficiently softened up to identify his employer as Harlem mob boss Bumpy Jonas (Moses Gunn, from Rollerball and The Ninth Configuration). After a mostly unproductive interrogation session with Androzzi and his boss, Captain Byron Leibowitz (He Knows You’re Alone’s Joseph Leon), Shaft arranges a meeting with Bumpy himself in the hope of finding out just what in the hell is going on. It seems Bumpy’s daughter has been kidnapped by persons unknown, and because his line of work would make it highly inconvenient for him to go to the police, Jonas wants Shaft to handle the task of tracking down the kidnappers and getting the girl freed. Off the top of his head, Bumpy’s best guess is that the culprits are connected to the black militant front led by Ben Buford (Christopher St. John, of Hot Pants Holiday).

So Buford’s apartment is Shaft’s next stop, and he arrives just in time to barge in on a meeting of Ben’s revolutionary inner circle. He also arrives in time to see nearly the whole lot of them mowed down by a couple of men with submachine guns; only Shaft and Buford make it out of the building alive. While they sneak across the city to Shaft’s apartment, the detective turns his mind to the question of what’s really going on here. Buford swears he doesn’t have Bumpy’s daughter, and despite the long history of mutual antagonism between his militants and Bumpy’s gangsters, Ben really wouldn’t stand to gain much from the kidnapping. Vic Androzzi says something big is in motion on the underworld front, and it’s certainly possible that the guys with the machine guns were really after Shaft, having been sent by Bumpy’s enemies, rather than Buford’s. Finally, and perhaps most tellingly, the gunmen who wasted Buford’s lieutenants were white. The next day, Shaft and Buford go to see Bumpy, and the detective confronts Jonas with what he has pieced together: the kidnappers are mafia, and their aim is to use the Jonas girl as a hostage to give them leverage in the coming turf war between them and Bumpy’s mob. The one thing Shaft doesn’t understand is why Bumpy, who almost certainly knew all that already, would send him on a wild goose chase in the direction of Ben Buford, especially since doing so would seem just about guaranteed to get at least a few of Ben’s followers killed. The truth is not so hard to fathom, though. Bumpy needs to preserve his strength for the gang war, so he wants a third party to rescue his daughter for him. Shaft alone is no match for the mafia— it takes an army to wage that kind of battle. Ben Buford has an army, and with five of his men dead at mafia hands, he now has personal reasons to join the fight. All concerned will be paid handsomely, of course: $20,000 for Shaft, $10,000 each for Ben and as many of his followers as he sees fit to enlist, and another $10,000 to Ben’s militia for each of the men who died in the mafia raid on the tenement. Both sides accept each other’s terms, and the battle is joined.

It’s probably significant to its initial runaway success and continued popularity that Shaft is among the very few blaxploitation movies that were made by a black director. What’s more, Gordon Parks’s background was far removed from the drive-in fare that dominated the careers of most other blaxploitation filmmakers. He had been a renowned photojournalist with 25 years at Life magazine under his belt before coming to Hollywood, and his biggest claim to cinematic fame prior to Shaft was the acclaimed autobiographical drama The Learning Tree. So far as Parks was concerned, Shaft had nothing to do with exploitation, and everything to do with taking a traditional Hollywood tale, and retelling it from a black perspective. It was a logical approach to take, too, because the novel on which Shaft was based had been written with exactly the same motivation— journalist-turned-crime novelist Ernest Tidyman had never written a story about a black character before, and he wanted something to make his next book stand out from the crowd. The most noticeable effect of this treatment of the story is that Shaft came out far less cartoonish than the typical blaxploitation film, even despite the kitschy slang and the exaggerated racism of the villains. There are white good guys and black bad guys, and one of the most compelling things about the character of John Shaft is that his own personal strength and self-assuredness hold him above the color battles of his time. Shaft is too busy being a man to worry much about being a black man, and while he’s always ready and willing to trade verbal jabs with bigoted gangsters or to rib his white ally on the police force about the social gulf that will always separate them no matter how hard Androzzi tries to bridge it, Shaft never permits himself to be a victim or to believe that the world owes him anything that he can’t take with his own two hands. Shaft’s reaction in the face of white hostility indicates a man who knows the true measure of himself too well to care about impressing the small-minded and morally weak, while his dealings with Ben Buford and his Black Panther wannabes reveal a philosophy that could best be characterized, “Yeah, yeah— Fight the Power, whatever… Listen, I’ll be over here getting on with my life if you need me.” When seen in that light, it’s no wonder contemporary black intellectuals found Shaft so objectionable. They were in the middle of a struggle for the political and social advancement of their race, and then along came Gordon Parks with a movie made on the white man’s dime which seemed to argue implicitly that to carry on the fight for equality in nakedly political terms was at best irrelevant and at worst counterproductively naïve. The leading black philosophers countered that the real counterproductive naiveté lay in the idea that revolution was unnecessary, and that blacks could advance their position simply by refusing to live as though they were second-class citizens. In the context of the 1970’s, the civil rights thinkers had a point— but then again, Parks himself got to be where he was essentially by doing it Shaft’s way. And now that the decisive battles of the cultural war against racism have been fought and won, the uncompromising self-reliance that John Shaft represents looks more powerful and meaningful than ever before.

I think Gordon Parks would be the first to say that to view Shaft solely— or even mainly— in sociopolitical terms would be to miss the point, however, so let’s take some time now to look at it as just another crime film. Simply put, it’s a brilliant piece of work. You could scarcely ask for a more effective reworking of the traditional pulp detective tale, and while the story itself is extremely thin, Parks does a masterful job of rendering it visually. His long years of photographing poverty and urban blight serve him well here, and Shaft’s vision of the crumbling slums of 70’s Harlem is easily the most convincing ever achieved by a major-studio film. Richard Roundtree, as I’ve already remarked, inhabits the role of John Shaft with such ease and authority that it’s nearly impossible to believe the actor and the character have next to nothing in common. Moses Gunn gives a shockingly powerful performance as Bumpy Jonas, humanizing a vile and corrupt character with a success that few other actors have achieved. And Isaac Hayes’s score is nearly magical. Whereas the overbearing funk soundtracks of most blaxploitation movies now seem hilariously dated, Hayes’s music invokes its era in a way that transports the viewer back into it, conjuring up the lifeforce of the early 70’s instead of just calling attention to the foibles of the age. Shaft is an impressive achievement all around, and if any movie deserved to touch off a half-decade craze, then this was the one.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact