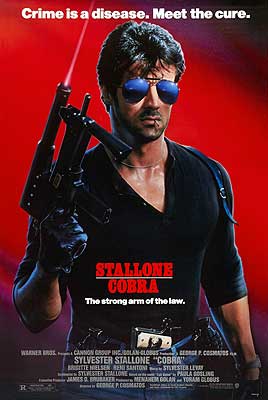

Cobra (1986) -***½

Cobra (1986) -***½

We have here a movie that deserves a much loftier place in the 80’s cult canon than it has thus far attained. Crime thrillers that were really horror movies at heart— films that traded on the audience’s fear of crime rather than the allure of the outlaw lifestyle or the intricacies of law-enforcement procedure— first became a notable phenomenon in the late 1960’s, but it wasn’t until the following decade that the subgenre really hit its stride. Nor did it take much time at all for it to mutate almost beyond recognition. At the beginning of the cycle, the terror of crime was, if not a new phenomenon, then at least a newly important one, and the films that explored it mostly did so in an appropriately serious and thoughtful manner. Things were different in the 80’s, though. By then, crime rates had been rising sharply and steadily for more than 20 years, and a large segment of the public was all out of patience with examining the issue and attempting to understand its root causes. What they wanted was action, and the more extravagantly decisive the better. In the real world, that meant widespread support for increasingly draconian sentencing policies, diminishing concern for the rights of the accused, and a marked shift in the preferred balance between rehabilitation and revenge in the criminal justice system. In the reel world, meanwhile, it meant a growing demand for movies that portrayed criminals as subhuman beasts without any intelligible motive for their misdeeds, fit only to be shot on sight by monster-slaying vigilantes— or by monster-slaying cops who could scarcely be distinguished from vigilantes. The Dirty Harry and Death Wish series may be the best remembered of that new breed, but for my money, Cobra is the ultimate example of the form, the gloriously inglorious culmination of the trend that began with the likes of Targets and The Boston Strangler.

The subhuman beasts in this case are a sort of crime cult led by a serial killer known to the Los Angeles press as the Night Slasher (Brian Thompson, from Fright Night, Part II and Dragonheart). No, I don’t understand how that’s supposed to work either, and when Thompson asked screenwriter Sylvester Stallone about his character’s motivation, the reply was an unhelpful, “He’s evil.” In practice, the cultists mostly seem to gather in a defunct swimming pool to clash axes together rhythmically over their heads. And strangely, no one seems to have caught on that the Night Slasher has a literal army of accomplices, even though the physical evidence at each of his fifteen crime scenes has to indicate half a dozen assailants or more at a time. Nor has anyone apparently drawn the obvious connections among all those times lately when some hoodlum has shown up to waste people at random in a public place, ranting all the while about “the New World.”

One such incident is in progress as the opening credits roll. The perp (Mario Rodriguez, of Toolbox Murders and The Crow) is such an asshole that he parks his motorcycle in a handicapped space when he arrives to take the shoppers at the King Foods grocery store hostage. That pretty much tells you everything you need to know about the level of nuance and sophistication that you can expect from this film. The police response led by Detective Lieutenant Monte (Andrew Robinson, from The Puppet Masters and Hellraiser) is swift, attention-getting, and totally ineffectual at resolving the situation. Eventually, Monte’s superior, Captain Sears (Art LaFleur, of Zone Troopers and The Blob), yields to the inevitable and calls for a different sort of backup. Enter Marion “Cobra” Cobretti (Stallone) and his partner, Sergeant Gonzales (Reni Santoni, from The Student Nurses). Cobretti and Gonzales belong to the “Zombie Squad,” an outfit whose evocative name seems to contain about as much actual meaning as “crime cult.” In any case, Cobra’s the cop whom you call when you want people to die, and you don’t care overmuch what, if anything, they’re guilty of; I bet Daryl Gates hired him personally. He makes short work of the gunman, and takes time out to score a few points off of the lily-livered liberal journalists who throng the King Foods parking lot in the aftermath.

Elsewhere and later, the Night Slasher ups his kill count to sixteen. He and several of his followers orchestrate a strategic fender-bender underneath an overpass, and pig-stick the hapless rear-endee from behind while she argues futilely with the big-haired bitch (Lee Garlington, from Psycho II and The Seventh Sign) who was driving their van. But before the killers have a chance to pack up the victim’s body for transport to wherever they intend to dump it, fashion model Ingrid Knudsen (Brigitte Nielsen, of Red Sonja and Galaxis) drives right through the scene of the crime and has an unnerving moment of eye contact with the Night Slasher himself.

Obviously the crime cult can’t leave a loose end like that hanging around. Fortunately for them, the aforementioned big-haired bitch is the aptly-named LAPD patrolwoman Nancy Stalk. The Night Slasher makes a point of memorizing the witness’s license plate number, and Stalk runs Knudsen’s tags at work the next day. Now armed with Ingrid’s home address, the cultists lay an ambush for her in the parking garage beneath her apartment building. Knudsen has not yet begun to be a pain in the Night Slasher’s ass, however, for although he and his men kill Ingrid’s photographer and would-be boyfriend, Dan (David Rasche, from Bigfoot: The Unforgettable Encounter and Men in Black 3), the target herself manages to reach safety. For some reason, it falls to Cobretti and Gonzales to interview her in the hospital later (I gather that she was admitted more for shock and nervous exhaustion than for any injuries as such), and Cobra catches on at once that the attack on her is connected to the Night Slasher murders, even if that point eludes Monte and Sears for the moment.

The link becomes unmistakable the following night, when the crime cult stages simultaneous attacks on Cobretti’s apartment and Knudsen’s room at the hospital. Again, though, the operation doesn’t pan out to the killers’ liking. Cobra is more than a match for the assassins sent against him, and he reaches the hospital in plenty of time to save Ingrid. Furthermore, because Stalk faked a call from headquarters pulling Gonzales off of guard duty before the hospital hit, Cobretti has even begun to suspect that there’s a mole in the department. Even now, Sears and Monte are resistant to doing things Cobra’s way, but they’re not so pig-headed that yet a third attempt on Ingrid’s life— this one provoking what might just be the most wildly irresponsible motor vehicle chase in cop movie history— won’t convince them. Cobretti at last gets the captain’s permission to take Ingrid out of the city, to a safehouse in the little town of San Remos up north. There, he’ll use the cultists’ determination to kill her at any cost to set a trap of his own.

What appeals to me most about the reactionary action movies of the 1980’s is that they combine total earnestness and sheer absurdity in a way that has rarely been matched by nominally non-fantastical films of any other genre or era. Where else would you see a crime cult dedicated for no clear reason to creating a New World of chaos and terror put forward as something that might exist in the real world of the present day? Where else do plainclothes cops drive 1950 Mercury hotrods with blowers and nitrous tanks— not just in their private lives, but while actively on the job? (Note, by the way, that while Cobretti’s Merc has nitrous tanks, it conspicuously lacks a radio, a siren, or a dashboard flasher dome. Note as well that he lets none of those shortcomings deter him from using the car for a high-speed chase through the streets of Los Angeles at midday.) Where else will you see a laser sight treated as a sensible accessory for a submachine gun? (In case it’s not obvious what’s so silly about that, remember that laser sights are for those times when you care a lot about accuracy, but don’t expect to get much time to line up a shot. If you cared at all about accuracy, you wouldn’t be using a submachine gun in the first place.) Nor does Cobra waste a single second in cuing us to expect a sterling example of the reactionary action subgenre. The first thing we see is a roving extreme closeup on Cobretti’s two signature props: the strike-anywhere match which he chews perpetually and his custom-made, custom-chambered Colt M1911. (Would you believe the pistol has an ivory grip inlaid with the image of a cobra in full threat display? Of course you would.) As director George P. Cosmatos camera-fondles these totems, Stallone rasps in voiceover, “In America, there’s a burglary every eleven seconds… an armed robbery every 65 seconds… a murder every 24 minutes… and 250 rapes a day.” Then Cobretti draws and fires straight into the audience, and the title KABOOMs into existence behind the slow-motion animated bullet. There’s not a trace of irony to be found, either.

It’s surprising, then, that Cobra occasionally manages to be somewhat effective in spite of itself. That car chase I keep bringing up, silly as it is from a real-world perspective, is a genuinely exciting display of stunt driving. The three-stage climax begins with a creditable siege sequence at the San Remos safehouse, progresses through a nice bit of George Miller plagiarism as Cobretti and Ingrid flee their overrun hideout, and finishes up with what remains my all-time favorite showdown between burly bruisers in an inexplicable steel mill. And throughout, Cobra benefits from a superb (if extremely broad) performance from Brian Thompson as the Night Slasher. This movie was my introduction to Thompson, in fact, and it immediately earned him a place alongside Brion James in my personal pantheon of jobbing heavies. He’s naturally at his best here when Stallone and Cosmatos let him be a silent figure of hulking and tightly wound menace, but my God, Thompson almost sells that stupid speech the Night Slasher gives right before he and Cobra go at it in the foundry! Not bad at all for having nothing more to go on than “He’s evil.”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact