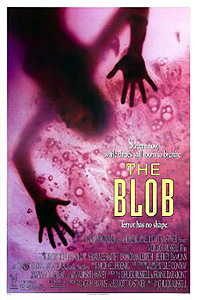

The Blob (1988) ***

The Blob (1988) ***

There are probably as many reasons to remake a movie as there are filmmakers producing remakes, but it seems to me that there are four motives that have steadily recurred throughout the years. (Recently, we have seen a fifth— because the folks with the cameras have nothing better to do— come into vogue. With any luck, this fashion won’t last any longer than parachute pants did.) Three of these motivations are unquestionably valid, and have often led to the creation of exceptionally good films; the fourth... well, we’ll get to that in a bit. Sometimes a movie gets remade because the original was an adaptation of a novel or short story to which it simply did not do justice, and some director or other wants to try their hand at a more faithful treatment. The classic example of this strain would have to be John Carpenter’s The Thing. Then you’ve got your remakes that stem from somebody coming up with an inspired new story to tell using the setup from an earlier movie; David Cronenberg’s version of The Fly springs immediately to mind as a case in point. Then there are movies like the Hammer Film Productions take on The Mummy, which looks like a case of subsequent filmmakers going back to make up for their predecessors’ mishandling of a good idea. Again, in each of those three categories, I’ve seen more good remakes than bad. Unfortunately, it’s the fourth major current of remakes that commands the most attention, and with good reason— it’s broader than any of the other three, and the stench kicked up by most of the movies within it is just too strong to ignore. I’m talking about remakes that owe their existence to little or nothing more than the advance of special effects technology, and there’s no shortage of noteworthy examples. The Dino De Laurentiis-John Guillermin King Kong. The Dean Devlin-Roland Emmerich Godzilla. Jan De Bont’s The Haunting. As bad as the bulk of such movies are, though, there a couple of remakes even here that have some merit to them, and Chuck Russell’s 1988 version of The Blob is right up near the head of that very small class.

Just like in 1958, what we have here is a small town nestled in the heavily wooded hills, seemingly far from the nearest major population center. And just like in 1958, the inhabitants of this town with whom we shall mainly concern ourselves are its teenagers. In the Good Kids’ corner, taking over (or so it would seem) for Steve McQueen, is Paul Taylor (Donovan Leitch of Cutting Class), high school football hero— well, sort of. Paul is infatuated with a cheerleader named Meg Penny (Shawnee Smith, from the TV mini-series adaptations of The Stand and The Shining), a girl at least as clean-cut and innocent as he is. Sliding toward the other end of the social scale, we come first to Paul’s friend, Scott (Ricky Paul Goldin, of Piranha II: The Spawning and Mirror, Mirror), then to official town troublemaker Brian Flagg (Kevin Dillon). If Paul is the Steve McQueen character, and Meg is Aneta Corsaut, then Flagg is this movie’s answer to Robert Fields, the old version’s head hotrodder. Like him, Flagg isn’t really such a bad kid, and might easily get his life turned around if the adults in town would just stop hassling him for a while. Naturally, Flagg’s arch-nemeses are Sheriff Geller (Jeffrey De Munn, from Christmas Evil and The Hitcher) and Deputy Briggs (RoboCop’s Paul McCrane), both of whom seem positively gleeful that the boy’s 18th birthday is coming up, and with it the prospect of being able to send him to real jail.

Anyway... One night, while Paul is taking Meg out on their first date, while Scott is trying to score with some girl who isn’t quite trashy enough to give him what he wants, and while Flagg is out in the woods repairing his motorbike (which he damaged while attempting to perform some stupid stunt earlier that afternoon), trouble descends our idyllic setting in the form of a meteorite landing in the woods. The only person on hand to witness the impact is an insane vagrant, who notices that something is moving inside the thing when he goes to investigate. Widening the crack in the meteorite’s surface with a long, heavy stick, the bum digs out a small mass of thick, translucent slime. He never does get much of a handle on what it is, but it rapidly becomes clear that the thing is a lifeform of some kind. Slithering up the stick with alarming speed, the blob wraps itself around the vagrant’s hand and begins digesting his flesh. The indigent’s frantic flight through the forest leads him first to Brian Flagg, and then to the road that Paul and Meg are traveling on the way to their date. Paul accidentally runs the injured man down, but when he sees Flagg chasing after him, he jumps to conclusions and insists that the other boy accompany him and Meg to the doctor’s office to get help for the bum.

That help ends up being entirely unavailing. Flagg leaves in contemptuous disgust at the receptionist’s bad attitude, and while Paul and Meg fill out endless paperwork for a man whose name they don’t even know and the doctor consults in a leisurely manner with another patient, the blob from space gradually consumes practically all of the vagrant’s body. Paul discovers how hideously awry things have gone only when, in impatient frustration, he goes into the waiting room to check on the homeless man. Meg and the doctor respond to Paul’s urgent cries for help just in time to watch the boy— and then the doctor as well— get engulfed and absorbed by the blob, which has by now added most of the vagrant’s biomass to its own. The creature has slinked off into the night by the time Geller and his police force show up in answer to Meg’s terrified phone call, and Deputy Briggs immediately decides that Brian Flagg is really to blame for Paul’s disappearance.

Traumatized as she is by just having witnessed the exceptionally messy demise of her brand new boyfriend, Meg still has the presence of mind to realize that the killer blob is on the loose somewhere, and focusing on that, she sneaks out of her house after her parents have gone to bed and goes looking for Brian Flagg. Flagg (who has just been released from an entirely fruitless good cop-bad cop session with Geller and Briggs) knows nothing about the blob as yet, beyond that there was something weird on the old bum’s hand. He doesn’t initially believe Meg’s story about what really happened to Paul, but he comes around when the gelatinous monster oozes up through the plumbing to attack the diner in which he and Meg were discussing the subject. Meg and Brian narrowly escape by locking themselves in the walk-in freezer. The blob tries to ooze under the door after them, but it doesn’t like the temperature in there at all; in fact, it leaves a few flash-frozen particles of itself on the floor when it turns around to go after Fran Hewitt, the diner’s amiable head waitress (Candy Clark, from Cat’s Eye and Q), and Sheriff Geller.

So far, the main difference between this Blob and the old one has been this version’s willingness to kill off characters whose counterparts survived to see the closing credits in its predecessor. But as the movie wears on, two more points of divergence become increasingly evident. Most conspicuously, the monster has been given a new origin story. As the situation in town spirals farther and farther out of control, a team of containment-suited military types under the leadership of the none-too-trustworthy Dr. Meddows (Joe Seneca) arrives to take matters in hand. It turns out that meteorite wasn’t a meteorite at all, but rather a Defense Department satellite that had been sent up to test whether or not the military’s latest top-secret bacteriological weapon could be deployed as a space-based deterrent. Evidently the unfiltered cosmic radiation the synthetic germ encountered up above the atmosphere is responsible for its mutation into the all-consuming blob that now threatens Meg Penny’s sleepy little hamlet. I personally wasn’t too happy to see this change from the original film. Already by 1988, my patience for the “secret military experiment gone horribly wrong!!!!” plot device had worn very thin indeed. Far more successful, to my way of thinking, is the other major transformation the remake works on the basic story. While the monster in the original The Blob was just a big mass of amorphous protoplasm, roaming mindlessly and more or less at random around town and absorbing anyone foolish enough to get in its way, the creature in this version has a much deeper bag of tricks. It attacks most often by extruding tentacles and pseudopods, which shoot out like a chameleon’s sticky tongue to snag its prey. Not only that, this blob is shockingly fast, apparently using a combination of its stickiness and its greater bodily cohesion (as compared to the original) to lever itself around in an approximation of a running gait. It’s also noticeably brighter than the 1958 blob. While it clearly doesn’t qualify as intelligent life, the new blob does seem to possess a certain amount of low animal cunning— best displayed in the scenes in which it is depicted as creeping up onto the ceiling to fall on its prey from above.

In any case, it seems pretty obvious that the new, deadlier blob— which could not have been realized at all convincingly with the special effects technology of the late 1950’s— is the real reason why this movie was made. There are a few commendable attempts to give this version of The Blob a personality distinct from the original, and some of them actually work, but it’s hard to argue with the proposition that advances in special effects were the filmmakers’ primary inspiration. Not that there was much chance of it being any other way, mind you— The Blob hadn’t exactly been bursting with unexplored subtext or neglected meaning to begin with, after all. Nevertheless, the remake works. It lacks some of the original’s charm, and it doesn’t try nearly hard enough to duplicate its predecessor’s unexpectedly multi-dimensional characterization, but the story takes quite a few brave and even shocking turns, and the new take on the monster ups the ante nicely. If more remakes turned out like this, they wouldn’t have anything like the bad reputation they’ve acquired since the 1940’s.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact