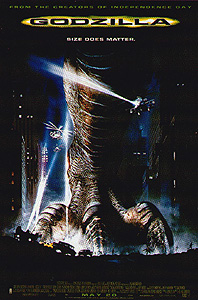

Godzilla (1998) *½

Godzilla (1998) *½

And now let’s meet our special guest stars for tonight’s episode of “How the Mighty Have Fallen.”— everybody give a big hand to Dean Devlin and Roland Emmerich! These two filmmakers have been well outside the limelight for some years now, but back in the 90’s, Devlin and Emmerich were movers and shakers on a grand scale. For most of a decade, these men had their fingers on the pulse of ass-sucking, cranking out one horrible mega-budget action movie after another and proving in the process that the average American moviegoer cared not one whit for intelligent scripting, competent performances, effective pacing, or even basic continuity and common sense. No matter how unapologetically awful it might be, a Devlin-Emmerich explosion movie could be counted upon to recoup even the most eye-popping production cost and go on to make a tidy profit. Then along came two films in fairly rapid succession which not only did disappointing box office, but got bitchslapped by critics and fans alike. While a look at their filmographies suggests that it was The Patriot that really wore the luster off of Devlin and Emmerich in the eyes of Hollywood, their willfully perverse take on Godzilla probably did more to sully their reputation with audiences.

Before I go on, there’s a piece of mistaken conventional wisdom that needs to be addressed. The Devlin-Emmerich Godzilla was not a financial failure in the strict sense. Despite its huge expense, it did indeed make money, and quite a lot of it. The trouble was that most of that money was made in a belated and gradual manner at the video store, and when a studio spends fully a year hyping the shit out of a movie that cost them $120 million (and some sources claim a figure closer to $150 million) even before factoring in promotional expenses, they really do expect to be up to their eyeballs in cash before the film is out of the theaters. Godzilla did not do that for Columbia-Tri-Star. Despite debuting on a record number of screens (well over 7000) right at the beginning of 1998’s summer blockbuster season, Godzilla’s opening-week performance was well below what had been expected of it. Then box-office grosses plunged by more than two thirds during the second week, and again by half in week three, presumably due to horrible critical write-ups and the stridently negative word-of-mouth circulated by people who saw the film during those first seven days. So while Godzilla turned a profit, it also left 7000 screens’ worth of conspicuously un-busted blocks behind it— evidently size mattered significantly less than the studio’s annoyingly ubiquitous advertising slogan would have it. Sony (Columbia-Tri-Star’s corporate overlords) still planned on making a sequel as recently as 2000, but significantly, they did not want Devlin and Emmerich involved. Even those plans fell by the wayside thereafter, and today the American Godzilla remains as dead as his Japanese counterpart was supposed to have been in the late 1990’s.

Fans of the original who habitually refer to this movie as GINO (Godzilla in Name Only— I prefer the more euphonious Fraudzilla, myself, but it’s really too early in the review to be going off on tangents like that) may be surprised at how closely in keeping with the traditional spirit the first act really is. After an opening credits montage establishing a series of nuclear weapons experiments in French Polynesia, set amid islands teeming with numerous species of reptiles (incidentally, so far as I know, none of the lizard species depicted here can actually be found in French Polynesia), we cut to a Japanese fish-canning ship sailing through a stormy South Pacific night. The cannery vessel’s sonar operator alerts the captain that there’s something extremely large headed right toward them at high speed, and moments later, the ship is rocked by a tremendous impact. Something— it looks like a set of gigantic claws— tears through the hull, a mammoth cylindrical object swings through the air to shatter the bridge, and the vessel goes down with nearly all hands. The sole survivor winds up in a hospital operated by the French government, where a worried-looking secret service agent named Philippe Roaché (Jean Reno, of The Professional, who would lend his considerable abilities to another undeserving remake by signing on for the 2002 version of Rollerball) attempts to interview him about the shipwreck. All Roaché gets out of the sailor is a single, enigmatic word— “Gojira”— whispered repeatedly and with palpable horror. (This, by the way, will be the last time palpable emotion of any kind makes an appearance in Godzilla. Kudos to you, apparently uncredited old Asian guy!)

Similar strange things begin happening along a path leading off to the northeast from the site of the wreck, and the United States Nuclear Regulatory Commission sends biologist Niko Tatapoulos (Ladyhawke’s Matthew Broderick, who apparently didn’t learn his lesson about appearing in ill-conceived remakes of famous genre films either— he was in the roundly castigated 2004 version of The Stepford Wives) is called in to support Dr. Elsie Chapman (Vicki Lewis) in her efforts to get to the bottom of it all. Why is the NRC suddenly interested in shipwrecks and razed Panamanian villages, and why do they want a scientist whose main field of research is in radiation-induced gigantism among earthworms at Chernobyl? Well, as Tatopoulos discovers when he gets to Panama, whatever is crossing the globe wreaking havoc as it goes happens to have left a trail of three-toed footprints about four feet deep and more than forty feet long across the isthmus, footprints which are alarmingly radioactive. Chapman and Tatopoulos go next to Jamaica, where another cannery ship has been found stranded on the beach, its hull ripped to shreds in a pattern that strongly suggests the action of an animal’s claws— assuming, of course, that the animal in question was only slightly less massive than the ship itself. Finally, the scientists and their military entourage arrive in New York, the home port for a flotilla of fishing trawlers that something huge dragged down under the sea.

New York, coincidentally, is also the home of Audrey Timmonds (Maria Pitillo), Tatopoulos’s ex-girlfriend, who now works as a personal assistant to WIDF News anchorman Charles Caiman (Harry Shearer, a regular voice-actor for “The Simpsons,” whom I, for one, know better as Spinal Tap’s Derek Smalls). Audrey is angling for a promotion, but her friends and coworkers, Victor (Hank Azaria, another “Simpsons” cast-member) and Lucy (Arabella Field) Palotti, are both of the opinion that she isn’t nearly selfish or aggressive enough to make it in the cutthroat world of New York television journalism. That, in case you were wondering, is our standard lead-in to the subplot in which Audrey becomes the key WIDF employee on the scene when the NRC’s monster swims up the East River and wades ashore in Manhattan. The creature is a huge reptile resembling a theropod dinosaur easily 200 feet long. It smashes everything it touches as it stalks through the city, and Mayor Ebert (Michael Lerner, of Strange Invaders and Maniac Cop 2) has no choice but to cooperate when Colonel Hicks (Kevin Dunn, from Transformers and Stir of Echoes), the commander of the NRC scientists’ military escort, orders the city evacuated. (And yes, Mayor Ebert is indeed intended as a dig at film critic Roger Ebert, who had given Devlin and Emmerich’s previous movies exactly the drubbings they deserved. Incredibly, having gone so far out of their way to set the stage for vicarious score-settling, the filmmakers never get around to the expected scene of the monster stomping on the mayor. That’s right, folks. It’s not just petty— it’s petty without a payoff!)

It seems difficult to believe, but the monster somehow manages to shake loose the soldiers who were charged with tracking it around Manhattan. Sergeant O’Neal (Doug Savant, from Trick or Treat and Maniac Cop 3: Badge of Silence), apparently the top enlisted man attached to the monster-hunting effort, soon discovers that it made its escape by burrowing into the ground at the 23rd Street subway station. Luckily, Niko Tatopoulos has had some time to ponder the question of the creature’s biology, and he considers it likely that the monster subsists on fish— why else would it have attacked all those trawlers and cannery ships? With that in mind, he has O’Neal set a trap in which thousands of fish are dumped in the street at a wide intersection; the monster will smell the fish, crawl out of its hole, and walk straight into enough firepower to chew up an armored division and spit out bottle caps. What nobody has figured on is that the creature can run faster than an attack helicopter can fly, and has a body temperature so low that heat-seeking missiles will ignore it and lock onto the nearest building instead. The army not only chases the monster back into its hidey-hole without appreciably harming it, but manages to do more property damage than its quarry had even considered up to then.

Meanwhile, Niko and Audrey have run into each other, with Audrey using a press pass stolen from her boss to make her look like a full-fledged reporter. She is therefore on hand when her ex discovers, by means of a home pregnancy test, that the monster either has just laid a clutch of eggs or is soon going to. She also sneaks a peek at the “top secret” videotape showing the destruction in Panama and Jamaica, and the old Japanese sailor lying in his hospital bed chanting “Gojira” over and over again. Recognizing that the tape represents serious news, and that she’s the only civilian in the country who knows about it, Audrey pockets the tape while Niko is off having his stories of pregnant monsters scoffed at by the military brass. So who’s too meek and ethical for media success now, eh? Unfortunately, all Audrey manages to accomplish with this subterfuge is to screw everybody, herself included. Caiman gets his hands on the tape before it goes on the air, and edits himself in as the reporter of the story (in the one bit of humor that really works, the monster gets dubbed “Godzilla” as the result of Caiman’s careless pronunciation of the Japanese sailor’s recorded mutterings); the generals see the broadcast and give Tatapoulos the boot for talking to the press; and Niko reacts with understandable disgust when he figures out what Audrey has done to him. This leaves us with a giant monster on the loose, untold scads of baby giant monsters soon to be born, and the only person not too pig-headed to deal with the situation in a productive manner out of a job. Luckily, Philippe Roaché is on the case, too. Posing as insurance adjusters, he and several of his men (all of them named “Jean-Something,” by the way— I think it’s supposed to be a joke, but I honestly can’t tell) have infiltrated New York on a mission to destroy the monster. They know it was their government’s H-bomb experiments that gave the creature life, and they’re determined to make sure the public at large— whether American, French, or Panamanian— never finds out. Consequently, they’re Niko’s natural allies in the quest to find the monster’s nest, and Audrey’s best bet for getting back to the center of the story, giving that bastard Caiman a scooping he’ll not soon forget.

Anytime someone sets themselves to the task of updating an extremely old and extremely iconic movie, the first decision they must make is what to do differently. After all, if you’re just going to do the old movie over again, then why bother? (We will attempt to answer that very question whenever I get around to reviewing Gus Van Sant’s Psycho…) What Devlin and Emmerich planned to do, apparently from the very beginning, was to naturalize Godzilla, to make him an animal instead of a monster. They had their production designers turn to the latest thinking on dinosaur biology to create a look for Godzilla that was in keeping with the insights of modern paleontology. They devised what they hoped were scientifically plausible motivations for the monster’s behavior. And most contentiously, they eliminated such blatantly unrealistic elements of Godzilla’s character as his radioactive breath and invulnerability to conventional weapons. Combined with the New York setting, these revisions amount to a movie that plays more like a remake of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms than it does like a new version of Godzilla: King of the Monsters. That shouldn’t necessarily have been a problem, however, because the original Godzilla was really just a reinterpretation of The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms itself. No, what wrecks the American Godzilla is not what Devlin and Emmerich changed, but how they went about executing those changes.

Let’s begin with the point that most criticisms of the movie never get beyond— the monster itself. I, personally, like the new Godzilla design. With the possible exceptions of the humongous, Bruce Campbell-like chin and the odd fact that its lower jaw is twice the size of its skull, everything about the Tri-Star Godzilla displays the elegance of nature, and for the first half of the movie at least (more on this later), the computer animation used to create him is very well done by the standards of 1998. (Note, however, that it matters a great deal whether you’re watching Godzilla at home or in a movie theater. Something about the higher image density of the small screen brings out every little defect in the animation, pushing shots that were originally quite convincing perilously close to video game territory.) The problem is that by trying so hard to treat Godzilla as an animal, Devlin and Emmerich deprive themselves of the ability to say, “Who cares? It’s a monster!” when confronted with the shortcomings of their science— and those shortcomings are many and serious. For example, the filmmakers evidently have a very literal understanding of the term “cold-blooded.” Contrary to their apparent belief, cold-blooded animals do indeed radiate body heat; they merely have no built-in means of temperature control. If Godzilla really were no warmer than the surrounding air, he would suffer from extreme torpor, barely able to move at all. And what’s more, there is some cause to believe that a reptile as huge as Godzilla would achieve a kind of cheater’s warm-bloodedness simply through the greater heat retention that comes with added bulk. Some paleontologists theorize that the sauropod dinosaurs evolved their immense size at least partly as a way to circumvent the disadvantages of poikilothermy.

Then there are the behavioral troubles. By spending so much time on Godzilla’s feeding habits, Devlin and Emmerich make it perfectly obvious that there is simply no way for a predator of Godzilla’s size to find enough to eat. There’s a very good reason why the largest animals in the Earth’s history— the sauropods on land and the great whales in the oceans— have been, with very few exceptions, grazers or filter-feeders; in most ecosystems, the nutritional requirements of such massive bodies are just too high to be met by the uncertain and energetically expensive means of hunting and killing. Similarly, with the entire story hinging upon Godzilla’s reproductive mechanism (Tatopoulos discovers that Godzilla has come to Manhattan to nest), we are invited to scrutinize that mechanism at a level which it is unable to bear. The form of reproduction exhibited by Godzilla is known as parthenogenesis— literally, “virgin birth”— and it is indeed found among reptiles. Unfortunately for the filmmakers, it does not and cannot work the way they say it does here. In the scene where he learns that the monster is pregnant, Tatopoulos explicitly mentions that this is so even though Godzilla is male. But the entire concept of maleness is meaningless in the context of asexual reproduction— a male is the one who fertilizes, and in parthenogenesis, no fertilization occurs. Furthermore, it ought to be obvious that a reptile which reproduces asexually using all the equipment that evolved originally for sexual reproduction (eggs, ovaries, birth canals, etc.) would have to be female, anatomically speaking. I mean, whatever else happens, we may be certain that Godzilla isn’t producing eggs in his seminiferous tubules and laying them through his pecker! In the Toho movies, none of these issues ever come up. A monstrous allegory for nuclear annihilation doesn’t need a sustainable ecological niche or a physiologically comprehensible means of reproduction. An animal does.

There’s a second big pitfall inherent in attempting a “realistic” treatment of the 1950’s monster-rampage formula, and Devlin and Emmerich dive headlong into it, too. They’re just plain careless, and their attempts at realism draw attention to their carelessness. The example which will be most obvious to the average viewer is the matter of Godzilla’s size, weight, strength, and speed. When we see the footprints in Panama, they’re large enough to serve as parking spaces for the 42-foot helicopters flying over them, but when Godzilla makes landfall in New York, his feet are only slightly longer than the eighteen-foot Caprice Classic taxicabs he seems to take such delight in stomping upon. In one scene, he holds a taxi in his mouth and it’s a fairly snug fit; in another, he peers down a subway tunnel, his eye filling the tube’s complete diameter. During his initial stroll through the city, Godzilla’s footsteps trigger car alarms and cause vehicles to bounce on their suspensions half a dozen blocks away, but when he sets his foot down literally inches in front of Victor Palotti, the vibrations don’t so much as muss the photographer’s hair. In his first clash with the army, Godzilla outruns helicopters capable of 186 miles per hour; in the climactic scene, he is unable to catch a taxi that would be lucky to make 45 after all the pounding it’s taken. Then of course, there’s an incredible amount of Devlin and Emmerich’s trademark muddle-headedness concerning modern military equipment. Take the matter of missiles. A lot of people gripe about the American Godzilla’s death in a volley of AGM-84 Harpoons, but that doesn’t bother me. The Harpoon is an anti-ship missile. It has a 500-pound shaped-charge warhead that will punch through anything short of battleship armor, and Godzilla takes twelve of them before going down. I’d call that a respectable showing from a creature that’s supposed to be just an animal. But a few scenes earlier, just two Harpoons blow Madison Square Garden to kingdom come, and in the first battle, a pair of Sidewinders (air-to-air heat-seekers with 22.5-pound fragmentation warheads) tear the spire off the Chrysler building. Leaving aside the point that both of those demolition scenes are ridiculous for reasons including but not limited to the missiles lacking the explosive force necessary to cause that kind of destruction, these three incidents taken together show that Godzilla is six times as tough as Madison Square Garden, and 133 times as tough as the Chrysler building! So much for realism…

The really sad thing is, none of the foregoing addresses the worst defect of Godzilla, which is that it just plain doesn’t work as a story, and frequently fails even at the level of mindless spectacle, largely because its creators had no respect for the kind of movie it needs to be. At two hours and ten minutes, Godzilla is much too long, and devotes way too much time to the stuff we care least about: the desperately cliched romance between Niko Tatopoulos and Audrey Timmonds. Godzilla spends so much time running and hiding that he never really seems like much of a threat, and his absence from the bulk of the film’s midsection creates boredom rather than tension. The monster was off-screen for all but a few key scenes in Godzilla: King of the Monsters, too, but there the audience knew both that he could strike again at any time, and that no force on Earth would stop him when he did; it changes the dynamic of the downtime completely to have Godzilla cowering in a subterranean burrow to avoid confrontation rather than lumbering around on the seafloor working up an appetite. The sudden formula change at the halfway mark, when the focus shifts from destroying Godzilla to finding his nest and eradicating his young, derails the film’s momentum and cheapens Godzilla even further by revealing the extent to which it was intended as a Jurassic Park cash-in. (The Godzilla spawn are dead ringers for the latter movie’s Velociraptors.) And to add insult to injury, that changeover is accompanied by an inexplicable nosedive in the quality of the special effects, with the result that the scenes with the baby ‘zillas recall not Jurassic Park, but Carnosaur instead. Even with the less powerful, more naturalistic monster, this version of Godzilla didn’t have to be as bad as it is. After all, King Kong and the Rhedosaurus weren’t invincible, either, and this movie’s encouragingly effective first act shows how much could have been done with the premise. What it boils down to is that Devlin and Emmerich weren’t interested in making a monster movie, a genre for which they never attempted to conceal their contempt. They wanted to make an Irwin Allen-style disaster flick, and what we ended up with was an Irwin Allen-style disaster.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact