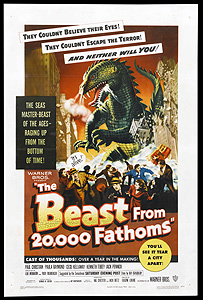

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) ***Ĺ

The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) ***Ĺ

Way back when, while writing about Godzilla: King of the Monsters and Them!, I took some time to discuss the atomic monster movie in general, to say a few words about its origins and about what itís capable of doing when itís at its best. Reviews of those two films really would be the best place to go into that subject, for not only did both movies come very early in the 50ís nuke monster cycle, theyíre also the best and most ambitious of that frequently witless and tawdry lot, and more thought and care had gone into them then had been devoted to just about all of their successors combined. But the atomic monster didnít begin with Them! or Godzilla: King of the Monsters; it began here, a year earlier, with The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms.

A first-time viewer would be likely to suspect as much on the basis of the first scene, even if he or she hadnít already known that to be the case, for The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms begins with a far more involved examination of a nuclear weapons test-firing than can be seen in any subsequent monster flick. Far up in the uninhabited Arctic wilderness of northern Canada, a joint team of scientists and soldiers from the US Army have spent the past 60 days gearing up for Operation Experiment, which the film only gradually reveals to hinge upon the detonation of a hydrogen bomb. The top scientist on the project is Dr. Tom Nesbitt (Paul Christian, aka Paul Hubschmid, from The Day the Sky Exploded); his military counterpart is Colonel Jack Evans (Kenneth Tobey, of It Came from Beneath the Sea and The Vampire). Once the bomb has gone off, Nesbitt and another scientist by the name of George Ritchie (Ross Elliot, from Tarantula and Indestructible Man) will ride out onto the ice pack to gather the data recorded by a set of blast- and radiation-proof monitoring devices forming a distant ring around ground zero. The first hint that their data recovery mission will not go according to plan comes just seconds after the detonation, when the research stationís radar operators briefly pick up a large blip moving around in the vicinity of the blast. The mysterious object is gone from the radar screen by the time Colonel Evans comes over to look at it, but the radar men estimate that it must have weighed in at somewhere around 500 tons.

Needless to say, Nesbitt and Ritchie will be seeing the phantom blip in person when they go out to check the data recorders. The scientists are forced to separate from the soldiers driving their snow cat when the ice around recorders 16 through 18 proves to be too badly torn up for the vehicle to traverse. Shortly thereafter, the high radiation levels in the area force the men to separate from each other in order to do their work more quicklyó which is just as well, seeing as thereís a blizzard moving in on them, too. While making his way to post 17, Ritchie catches a glimpse of a huge reptile prowling between the jagged crags of ice. Soon thereafter, he has a much closer brush with the creature, which leads to him falling into a shallow ravine and breaking his leg. The report from Ritchieís sidearm brings Nesbitt running, but the latter manís rescue efforts do the former little good. The monster is still in the area, and its massive bulk moving over the blast-damaged ice causes an avalanche that buries Ritchie alive and leaves Nesbitt with some injuries of his own. Nesbitt just barely has it in him to make it back to the snow cat.

The scientistís stories of a giant, dinosaur-like animal being thawed out by the H-bomb test meet with a solid wall of incredulity, of course. He even finds himself being examined by a psychiatrist in the New York hospital to which he is rushed after the soldiers bring him back to the headquarters of Operation Experiment. But Nesbitt knows what he saw, and heís sure itís no coincidence when the reports of a sea serpent sinking ships off the Atlantic coast of Canada begin showing up on the radio and in the newspapers. Sneaking away from the hospital, Nesbitt pays a visit to another scientist, Professor Thurgood Elson (Cecil Kellaway, from The Invisible Man Returns and Zotz!), dean of paleontology for some university or other. Professor Elson would like very much to believe Nesbitt, as the present-day survival of a Mesozoic reptile would be just about the coolest thing ever to happen for a man in his profession. Nevertheless, Elson is unable to give much credence to Nesbitt, pointing out the seeming impossibility of any animal lasting for 100 million years or more in even the deepest hibernation. Elsonís assistant, Dr. Lee Hunter (Paula Raymond, from Five Fingers of Death and Blood of Draculaís Castle), isnít so quick with her dismissals, however. At the very least, sheís certain that Nesbitt believes he saw a living dinosaur on the Baffin Bay ice pack. With that in mind, she invites Nesbitt over to her apartment, where she has him look through her collection of artistsí conceptions of various dinosaur species in the hope of pinning down just what Nesbittís monster was. After hours of thumbing through portfolios, Nesbitt finds a perfect matchó a 100 million-year-old, amphibious super-predator Dr. Hunter calls Rhedosaurus.

Now the question is one of finding corroborating evidence. Hunter suggests that Nesbitt look up the surviving sailors whose ships were supposedly destroyed by the creature, and try to convince them to look through the same pile of sketches he just did. If they also finger the Rhedosaurus as the culprit, then she and Nesbitt will have something concrete with which to make their case to Professor Elson. The first sailor Nesbitt talks to wants nothing to do with him; heís already been called a drunk and a lunatic by practically everybody in Nova Scotia, and thus understandably has nothing more to say on the subject of sea serpents. Nesbitt has more luck with Jacob Bowman (Jack Pennick, of Mighty Joe Young and 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea), former helmsman of the fishing boat Fortune. Not only does Bowman agree to look at Hunterís pictures, he also agrees with Nesbitt as to the identity of the monster that destroyed his vessel. Even Elson is convinced now, and the old man dives headlong into the effort to sell the authorities on the idea that a killer dinosaur is at large in the North Atlantic. Colonel Evans, unable to argue with a man who makes his living from dinosaurs, grudgingly pays a visit to his friend, Captain Phil Jackson of the US Coast Guard (Donald Woods, from 13 Ghosts and Door-to-Door Maniac), and asks him to keep his eyes open for anything suspicious. He doesnít have to wait long. Only a few days later, the Rhedosaurus trashes a lighthouse in Maine, and then moves on to Massachusetts, where it cuts a swath of destruction along the shore.

Elson thinks he knows whatís behind the monsterís movements. He believes itís following the Arctic Current south toward the Hudson Undersea Canyons, the place where the only known fossils of its species were discovered accidentally in a drag of the sea floor. The professor disagrees with Captain Jackson that this offers an excellent opportunity to destroy the Rhedosaurus, however. Singing that ever-popular 50ís refrain, ďThink of the benefit to science!Ē Elson wants instead to capture it alive. Naturally, that means heís going to have to see the thing in person first, and to that end, he secures the use of a Coast Guard cutter and a diving bell. Elson finds the Rhedosaurus, alright, but he has just enough time to express his amazement over the radio to Dr. Hunter before the monster, drawn by the diving bellís powerful floodlights, gobbles up the machine and the scientist with it. Then it leaves home on a course for New York City, where it comes ashore to make an even bigger nuisance of itself than King Kong did. After all, Kong was maybe half the size of the Rhedosaurus, and he didnít spread a lethal, 100 million-year-old plague behind him everywhere he went. Whatís more, the disease borne by the monster means that the militaryís hands are tied in trying to fight it off; the only weapons powerful enough to kill it would also aerosolize a substantial quantity of its blood, spreading the deadly infection over the whole of New York at the very least!

Perhaps the most interesting point about The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms is the way in which it has far more in common with the average atomic monster movie than do its better known descendants from the following year. This movie is much less overtly political than Them! or Godzilla: King of the Monsters. The allegorical freight it carries appears to be mostly an afterthought, less the product of any specific desire to send up warning flares about atomic power than of the simple need to provide an excuse for the monsterís existence. It is surely significant in this context that the Rhedosaurus is ultimately destroyed by another product of applied nuclear physicsó an avowedly anti-nuke movie would hardly call upon the power of the atom to dispatch its monster! The subtext is unmistakably there, however, even if director Eugene Lourie doesnít seem to know quite what to do with it. The destruction caused by the monster, while on a much smaller scale than what we have since become accustomed to courtesy of the Japanese, receives far more attention than had been the case in King Kong, and the most important feature of most subsequent atomic monster filmsó the uselessness of conventional weaponry against the monsteró is already present here, albeit in a strikingly different way. It isnít that the Rhedosaurus canít be harmed by conventional weapons, but rather that to kill it conventionally would be suicidal as long as it remains in a populated area.

Of course, it isnít necessary to dig below the surface to appreciate The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms, which works perfectly well as a straight-up monster flick. Technically speaking, this is one of the four or five best-made movies of its type that Iíve seen. Remarkably, it features a number of fairly good actors in the central roles (Cecil Kellaway especially is terrific), and never makes the mistake of asking them to do things that are beyond their abilities. Compare the way Kenneth Tobey is used here to his rather awkward turn as a romantic hero in It Came from Beneath the Sea for a particularly good illustration of the sort of missteps The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms avoids. And on the subject of romance, Iím impressed at Lourieís light touch with the relationship that inevitably develops between Doctors Nesbitt and Hunter. For once we have a romantic subplot that seems essentially plausible, and which is deployed in the service of the main story rather than as an interruption to it. Finally, thereís the Rhedosaurus itself. The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms marks the point at which Ray Harryhausen first emerged from the shadow of Willis OíBrien as a major talent in his own right. And because Warner Brothers had rather deeper pockets than Columbia (the studio for which Harryhausen did most of his work as a special effects artist), his work here suffers from none of the cut corners that would dog him later in his career. Consequently, the animation of the Rhedosaurus is some of the smoothest ever filmed, making it by far the most believable of all Harryhausenís frankly fantastic creations (by which I mean to exclude such things as the giant crab in Mysterious Island and the chess-playing baboon in Sinbad and the Eye of the Tiger). Beyond that, the design of the monster has an eleganceó even beautyó about it that has rarely been equaled since; apart from its excessive size (it looks to be about 150 feet long from snout to tail), the Rhedosaurus has the appearance of an animal that might really have lived at some point during the Earthís prehistory. Even if the nuclear angle hadnít made it the first representative of an idea whose time had come, The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms probably would have spawned imitators solely on the strength of its own inherent quality.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact