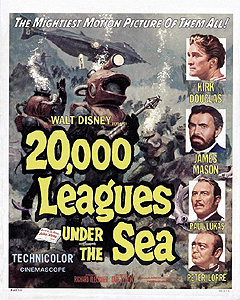

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) ****

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954) ****

My longtime readers will likely have gathered as much already, but Jules Verne has been my literary nemesis since the eighth grade, when Mrs. Stoddard had all of the kids in her first-period English class read 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. Verne is one of those rare scribes whose ungainly prose, lassitudinous narrative sensibility, and arrogant authorial voice can actually raise my blood pressure, and yet I feel compelled to read his books whenever I can get them cheaply, simply because he’s been so damned influential upon later writers and filmmakers whose work is important to me. There’s just too much cool stuff out there that would never have existed were it not for Verne’s writings, however noxious I may find them. And strangely enough, some of that cool stuff happens to take the form of movies based directly (at least in theory) on one of those books I can’t stand, yet end up reading anyway. We’ve already discussed two different film versions of Mysterious Island; now we’re going to take on Walt Disney’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, one of the most ambitious and effective science fiction movies of the 1950’s.

Something is sinking ships in the South Pacific. It appears to be some manner of animal with two huge, glowing eyes, but it’s at least 250 feet long, has a skull sturdy enough to break the back of an iron-hulled vessel without taking any apparent damage itself, and can outpace even the fastest steamer. Needless to say, no known marine animal meets anything like that description. Word of the creature’s activities has spread all over the globe, and commercial shipping in the Pacific is all but paralyzed. That last development greatly inconveniences Professor Pierre Aronnax of the Museum of Natural History in Paris (Paul Lukas, from The Ghost Breakers and The Monster and the Girl) and his secretary, Conseil (Peter Lorre, of You’ll Find Out and The Boogie Man Will Get You), who arrive in San Francisco with the intention of sailing on to Saigon. The two men can’t get passage on any ship in the harbor. The presence of a respected scientist does, however, get the attention of the press, and Aronnax soon finds himself beset with invitations to speculate about whatever it is that has shut down sea traffic between the Americas and Asia. Conseil warns his boss against commenting, but the professor can’t help himself; the result is a succession of exceedingly embarrassing front-page stories combining out-of-context and occasionally just plain bogus quotes from Aronnax with ludicrous illustrations to convey the impression that he believes the Pacific Ocean to be haunted by Saint George’s dragon. Some of those papers are sold in Washington DC, and before Aronnax knows it, he’s receiving a visit from John Howard (Carleton Young, from Reefer Madness and Buck Rogers), an agent of the United States government. Howard has an invitation of his own for Professor Aronnax. He wants him to serve as the scientific expert for an expedition to hunt down and destroy the Monster of the Pacific. In return, mission commander Captain Farragut (Ted de Corsia) will drop him and Conseil in Saigon before returning to the States. Conseil has some reservations, but the professor agrees to Howard’s proposal.

Farragut, as it happens, is a hard-headed, practical man, and he doesn’t put much stock in this foolishness about monsters. He thinks the whole mission is a waste of time. So, for that matter, does whaler Ned Land (Kirk Douglas, of Ulysses and Saturn 3), who nevertheless signed on for the bounty the government has placed on the mysterious creature’s head— it’s a job, after all, and with every ship on the West Coast cowering in port, there aren’t a lot of those to go around just now for a sailing man like Land. The three months of false alarms that follow the departure of Farragut’s ship would seem to validate the men’s opinions, too. The captain certainly thinks so, and he orders a halt to the mission. But no sooner has he done so than one of the lookouts sights a paddle-wheel steamer off to starboard, just as it is rammed and sunk by something huge under the water. Farragut turns his ship around and goes on the attack, but he accomplishes very little. Cannon fire doesn’t seem to hurt the monster much, Land in his longboat never gets a chance to try his harpoon against its hide, and even the hull of a fighting ship proves to be no match for the force of the thing’s charge. Aronnax and Conseil are knocked overboard by the concussion, and they are left adrift on the monster-haunted waters when Farragut’s vessel limps away from the scene of the battle, listing a good twenty degrees to port.

A dense fog rolls in with the sunset, so the castaways have no idea what they’re looking at when Conseil spies a dark shape above the water a few hundred yards away. Whatever it is, though, standing on it surely beats clinging to a bit of timber torn from their old ship’s upperworks, so the two men swim over to it just as fast as they can. What they find when they get there explains a great deal. The object is a ship of some kind, built completely of iron and with absolutely no conventional rigging. Moreover, what superstructure it possesses is immediately recognizable as the humps, fins, and cranium of the mystery monster. Oh— and there’s an open hatch on the uppermost superstructure deck. Aronnax immediately heads inside, and is rather startled to find the strange ship seemingly empty; after a bit of prowling, he figures out why. Through one of the vessel’s underwater viewports, Aronnax sees the crew, decked out in what would certainly constitute futuristic diving gear in 1868, conducting what appears to be a funeral on the ocean floor. (I guess Farragut’s gunners managed to do some damage after all.) Then the man whom we may presume to be the captain notices Aronnax in return. Conseil, proving once again that he’s the practical brains of this operation, starts hustling the professor topside as soon as he realizes what’s going on, arriving on the deck just as Ned Land fortuitously rows over in the longboat he was piloting when last we saw him. It isn’t much of a rescue, though, for the returning crew are able to overwhelm Aronnax, Conseil, and Land just as easily as they would have the professor and his secretary alone.

That brings us to Captain Nemo (James Mason, from Frankenstein: The True Story and The Night Has Eyes). He not only commands the huge submarine— which he calls the Nautilus— but designed it and oversaw its construction as well. The Nautilus is both his retreat from the human race and the instrument of his vengeance against it. What exactly is Nemo avenging, you ask? He’s not telling for the moment; all he’ll say when Aronnax invokes the conventions of civilized men to dissuade him against having Land and Conseil killed is that he is not a civilized man. Maybe not, but Nemo does have some ideas of his own regarding honorable conduct, and when Aronnax heads topside to drown with his friends rather than accept Nemo’s invitation to stay on aboard the Nautilus and thereby save himself (evidently the captain is a fan of Aronnax’s writing), Nemo aborts the dive and has all three of his uninvited guests brought back inside. So begins a 20,000-league voyage of undersea exploration that will take Aronnax and his companions all over the globe, seeing the world from a perspective most human beings never even imagine.

Since none of the men from upstairs are likely to be going anywhere, Nemo is perfectly content to show them all around his ship: his museum-like quarters, the navigation cabin, the conning tower, the engine room— even the submarine’s main power plant, which generates unheard-of quantities of electric energy through a process known only to Nemo. He takes them out onto the seafloor with him and his men when they stop in at the sunken island of Crespo, where the bountiful coral-reef ecosystem supplies most of the crew’s nutritional needs. Eventually, he even shows Aronnax— but Aronnax alone— the island slave-labor camp apparently run by the 19th century’s answer to Cobra, where he and the nucleus of his crew were held prisoner for years, harvesting chemicals with which to supply the world’s arms industry. Therein lie the roots of Nemo’s vendetta against the human race, in war and in the barbarities men commit in order to prepare for it— barbarities like the murder of Nemo’s family, whom his captors tortured to death in the hope of making him divulge the secret of what would become the Nautilus’s power supply. Any ship which Nemo believes is caught up in the international arms trade, he feels no compunction about destroying, as the professor and his friends learn when the Nautilus intercepts and sinks a vessel departing from the slavers’ prison island. Aronnax warms to Nemo somewhat once he knows how he became the man he is today, and he also has the siren-song of science to stop him begrudging his lost freedom. That doesn’t work for the other two men, however, who become more determined than ever to escape after they witness the destruction of the slaver ship. Ned conceives the idea to seed the ocean with bottled SOS messages the next time the Nautilus comes to the surface for any length of time, and Conseil helps him to carry out the plan. Furthermore, when the submarine grounds itself on a reef beside a Melanesian island (its rudder having been damaged in the ramming attack on the slaver steamer), the two men hope to turn a hunting expedition for which Nemo gives them permission into an escape from captivity. Nemo isn’t kidding, though, when he warns Land that the island is inhabited by cannibals who “eat liars with the same gusto that they do honest men.” Not only is the escape attempt thwarted, but the immobilized Nautilus is soon attacked by a native war party. That last is no problem, though. Nemo merely electrifies the outer hull, and the savages lose all interest in trying to come aboard.

What is a serious problem is the warship that happens along after the rudder has been set to rights, but before Nemo has managed to get his submarine unstuck. The ensuing battle does considerable damage to the sub’s propulsion system, and while the Nautilus does make its escape, it comes at the cost of a crash dive that cannot be brought under control until the vessel has gone some 5000 feet below its designed maximum depth. Even Nemo has never seen this stratum of the ocean before, which is just as well for him. Down here is the domain of Architeuthis, the fearsome giant squid, and a specimen not a whole lot smaller than the sub itself gets it into its tentacle-fringed head that the Nautilus would make good eating. In its way, this fight is even more desperate than the one against the gunboat, for nothing short of death will convince the squid to break off the attack. And in combination with the earlier clash, it leaves the Nautilus in no shape to continue its cruise. Nemo orders his helmsman to set course for Volcania, the virtually unknown island where he has his secret base, and where there are technological wonders beside which even the Nautilus pales. But when the sub comes to the surface to reconnoiter a few miles offshore, Nemo finds Volcania surrounded by fighting ships. I guess somebody found one of those bottles Ned threw overboard, huh?

I can’t believe I’m saying this about a Walt Disney movie adapted from a Jules Verne novel, but 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is really fucking good. You can see a few places where its creators have definitely Disneyed it up a little (Ned Land sings and does pratfalls, while Captain Nemo keeps a cigar-eating seal as a pet), but there are any number of respects in which they have just as conspicuously refrained from pandering to a juvenile audience. Most notably, the characterization of Captain Nemo is very prickly indeed, and James Mason throws himself into the part with all the well-mannered menace he can muster— which, as anyone who’s ever seen him play a villain before knows, is a hell of a lot. The movie does some interesting things with Conseil, too, which again show that its makers had more on their minds than charming theaters full of kids. Simply put, this is not Jules Verne’s Conseil, and neither is it the departure from the original that seems most natural for a 1950’s fantasy movie. In the book, Conseil is pretty well useless. He’s fairly young, not very bright despite a good memory for detail, and generally relegated to the role of comic relief. It would have been the perfect part for some cornball comedian, or alternately, the character could have been given a sex change and turned into a love interest for Ned Land. But instead, Disney cast Peter Lorre, and transformed Conseil from the professor’s faithful but inept sidekick into the man whose good sense and practicality are all that prevent Aronnax from making a total ass of himself at every turn. The revision makes the three passengers aboard the Nautilus equals in a way they never approached in the book, and makes sure all of them get a chance to earn some audience admiration. Placing a greater emphasis on the story’s anti-war angle helps, too, especially now that the Nautilus is fairly explicitly nuclear-powered. It puts Nemo in the same category as Dr. Serizawa in Godzilla: King of the Monsters— to a much greater extent than he had been in Verne’s hands, Nemo is now motivated by a horror of what use mankind might find for the fruits of his genius. It balances out and reshapes his revenge motive, in a way that makes him one of the most complicated characters ever to appear in a Disney film. This 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea has no simple answers to the questions Nemo raises, and it never tries to pretend otherwise.

On a more superficial level, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea is one of its decade’s most visually impressive movies. I’ve mentioned before that it took a great many years for the studio to recoup the cost of making this film, but any viewer will surely be grateful for the unusual investment. The Nautilus models are wonderful, striking a superb balance between real-world practicality and the need to look as cool as humanly possible. Furthermore, the submarine is in pretty decent accordance with 19th-century design sensibilities. Meanwhile, the sets, props, and costumes associated with the Nautilus display a similarly effective form of credible 1860’s futurism. The other ship models are just as good as the submarine, too, reflecting a startling attention to authentic detail. Captain Farragut’s vessel, for example, looks to have been based fairly closely on the 1870’s US Navy gunboat Alert. (Note, however, that this means the more Nelsonian sets representing the ship’s upper deck don’t quite accord with what we see in the long shots.) The squid miniature is one of the better monsters of its type, and the full-scale puppet with which Nemo and his sailors do battle after the colossal mollusk has forced the Nautilus to the surface is quite simply without peer in any other contemporary movie that I’ve seen. And of perhaps the greatest importance, all of these elements come together with the bare minimum of seams— in fact, there were some shots in which I honestly wasn’t sure whether I was looking at miniatures or something life-sized. It should go without saying that one almost never sees that in a movie of this vintage.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact