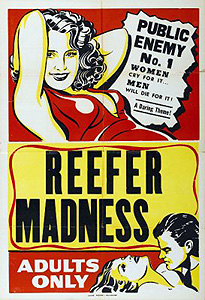

Reefer Madness / Tell Your Children / Dope Addict / Doped Youth / The Burning Question / Love Madness (1936) -***

Reefer Madness / Tell Your Children / Dope Addict / Doped Youth / The Burning Question / Love Madness (1936) -***

There were enormous numbers of drug-panic movies made during the 1930’s and 1940’s, but the vast majority are basically forgotten today. There are a few, though, that have stood… well, if not the test of time, precisely, then perhaps the test of attention; while their fellows have vanished into obscurity, they retain the power to reach out across the ages and make people of highly questionable taste sit up and say, “Man— I’ve got to see that!” Dwain Esper’s Marihuana: The Weed with Roots in Hell is one such film; Willis Kent’s The Cocaine Fiends is another. But no antique dopesploitation movie can match the present-day notoriety of Reefer Madness.

Its reputation is well earned. With all the old drug-panic films, distortion, exaggeration, and hyperbole were the name of the game, but you’ll look long and hard before you find a dope movie more hysterically alarmist, more flagrantly deceitful than Reefer Madness. Don’t believe me? Then get a load of this opening crawl:

The motion picture you are about to witness may startle you. It would not have been possible, otherwise, to sufficiently emphasize the frightful toll of the new drug menace which is destroying the youth of America in alarmingly increasing numbers. Marihuana is that drug— a violent narcotic— an unspeakable scourge— The Real Public Enemy Number One! Its first effect is sudden, violent, uncontrollable laughter; then come dangerous hallucinations— space expands— time slows down, almost stands still… fixed ideas come next, conjuring up monstrous extravagances— followed by emotional disturbances, the total inability to direct thoughts, the loss of all power to resist physical emotions… leading finally to acts of shocking violence… ending often in incurable insanity. In picturing its soul-destroying effects no attempt was made to equivocate. The scenes and incidents, while fictionalized for the purposes of this story, are based upon actual research into the results of Marihuana addiction. If their stark reality will make you think, will make you aware that something must be done to wipe out this ghastly menace, then this picture will not have failed in its purpose… Because the dread Marihuana may be reaching forth next for your son or daughter… or yours… or YOURS! |

Even that was not enough for the makers of Reefer Madness. Having thrown down that gauntlet, they then proceed first to bombard us with the traditional flurry of whirling newspapers with headlines about drug rings, then to invite us to attend a lecture given by principal Dr. Alfred Carroll (Joseph Forte, from The Crimson Ghost, who also had a small part in Them!) before a meeting of the Truman High School Parent-Teacher Association. After reiterating— sometimes verbatim— the main points of what we have just read on the screen, Carroll goes on to describe the diabolical ingenuity of dope smugglers and peddlers, cycling through a list of all the places where illicit substances may be carried and concealed (interestingly, he never thinks to mention purses or pockets…). He tells how marijuana is cultivated and processed; he describes the strategies used by the Bureau of Narcotics to find and destroy caches and shipments of illegal drugs (I love when they shovel the dope into a public incinerator— what, are they trying to get the whole town high?); he tries to give some indication of the scale of the crisis (“Marijuana grows wild in every state of the Union”— that at least really was true in the 1930’s). And somewhere in the midst of all this, Carroll makes the astonishing pronouncement that marijuana is more dangerous— far more dangerous, in fact— than opium, morphine, or heroin! Heroin, for the love of God!!!! Then he settles down a bit to tell his audience a little story about what happened in their own town…

Mae Colman (Thelma White) and Jack Perry (20,000 Leagues Under the Sea’s Carleton Young, who would soon do for birth control what he does here for marijuana in Race Suicide) are part of a big ring of traffickers in weed. Mae’s customers appear to be mostly musicians and artists attached to the jazz scene, but Jack does his business by throwing after-school parties for the local high school kids. Mae doesn’t approve, but neither does she try to do much of anything about it. Jack’s most valuable business asset is a college student named Ralph Wiley (Dave O’Brien, who seemed slightly more credible in The Devil Bat and The Bowery at Midnight— 26 was a lot older in the 1930’s than it is today), who not only smokes enough grass for five men, but likes nothing better than to be a corrupting influence on those younger than him. Bill Harper (Kenneth Craig) and Jimmy Lane (Warren McCollum, of Boys’ Reformatory) are two such kids. Bill is dating Jimmy’s sister, Mary (Dorothy Short, from Assassin of Youth), and Ralph also has the hots for her so hard he’s ready to drop his own girlfriend, Blanche (Lillian Miles), like a hot potato and go after her. Ralph has an easy enough time with Jimmy. All he has to do is introduce him to Jack, and within days, the boy is hanging out at the dope party crash pad, toking up and running old men over on the street in his big sister’s car. Bill, being rather stuffier, is a harder nut to crack, but he too falls from grace eventually. Principal Carroll notices his grades slipping, sees his performance on the tennis court take a nosedive, and gets to thinking that the boy has fallen in with a bad crowd. Mary starts to worry, too. Then one day, Bill goes over to Jack and Mae’s place, gets himself good and hopped up, and sleeps with the equally stoned Blanche. Mary comes looking for him, Ralph tells her that he went out with Jack a little while ago, and the scheming sleazebag takes advantage of Mary’s willingness to wait to make his move. First he offers her a cigarette, neglecting to mention that it contains something other than tobacco. Then he tries to romance her, but she still isn’t high enough to go for him, and at just that moment, Bill walks out of the bedroom and sees Ralph struggling to manhandle Mary out of her dress— here comes that “shocking violence” they told us about. Jack comes home to see the two boys wrestling on the floor, and he attempts to pistol-whip them into behaving themselves. He gets Bill, but Ralph is too quick for Jack, and soon the two of them are grappling over the loaded gun; only when it goes off do the combatants get hold of themselves, at which point they see that Mary has been shot dead. This despite the fact that Jack’s revolver was plainly pointed at the floor, while Mary was lying face-down on the sofa at the other end of the room! The physics of the situation aside, some quick thinking is called for at this point, and Jack gives the unconscious Bill the gun (after wiping off his own fingerprints), telling him that he shot Mary in his dope-induced stupor when he comes to a few minutes later.

And now we come to the courtroom drama phase of the proceedings. Don’t bother begging for a reprieve— I already tried that. Bill is found guilty of murdering his girlfriend, despite his lawyer’s efforts to convince the jury that a marijuana high is functionally equivalent to temporary insanity. Meanwhile, Jack and Mae go into hiding with Ralph and Blanche, and the two pushers become increasingly fearful that their compatriots may crack under the strain of fugitive living and go to the police. This they do, but not before Jack, acting on advice from the head of his drug ring, makes an ill-fated attempt to kill Ralph. The attack backfires, everybody turns state’s evidence, and Bill is saved from the gallows. Ralph, however, is now “incurably insane,” just like the opening crawl warned us.

It’s difficult to be certain just what to make of Reefer Madness, if for no other reason that any film which spends so many years being much talked about but little seen will inevitably give rise to a dense thicket of rumor, legend, and outright bullshit. Even the date of its release is a subject of dispute, with most current online sources favoring 1938, while the print literature on B-movies mostly favors 1936. (As is so often the case in these matters, the film itself is surprisingly unhelpful; in the print I saw, the opening credits noted that Reefer Madness was “copyrighted,” but failed to give a date even in the customary blurry and hard-to-read Roman numerals. My working hypothesis is that 1936 was the year of the movie’s original release under the title Tell Your Children, and that 1938 marked its first reissue under the more familiar name.) Over the years, it has been variously postulated that Reefer Madness was a lurid exploitation flick whose producers had no interest in anything other than lining their pockets, that the impetus for its creation came from a maverick right-wing church group, and even that it was shot at the behest of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics as part of Harry Anslinger’s infamous anti-pot propaganda campaign. As an example of how inextricably entwined fact and myth have become during the last seven decades, consider that no less authoritative a source than the Congressional Quarterly Researcher repeats the government propaganda line, but in a context which makes the attribution seem suspect at best— the CQR reference calls Reefer Madness a documentary, and gives a description which bears absolutely no resemblance to the actual film. Meanwhile, at least one of the stars reported in later years that director Louis Gasnier (best known otherwise for his Perils of Pauline and Exploits of Elaine serials from 1914) encouraged her to give the most outrageous performance possible (“Hoke it up” was the quote as I read it), and there are a few scenes which can easily be read as parodies of moments from more serious movies. I myself am inclined to reject what might be called the conspiracy theories of Reefer Madness’s origins. The “public service” fig-leaf was already an old trick by 1936, so neither the opening crawl nor the framing story with the PTA meeting should be taken at anything like face value. The production values— fully half the cast were bit-part and B-movie workhorses in Hollywood, and there’s no way a director with Gasnier’s resume could have been bought for community theater prices— argue powerfully against the theory that the funding for Reefer Madness came from a church. And while the government did indeed sponsor a great many film productions during the 1930’s, the vast bulk of those were documentary shorts destined for public school classrooms and military training seminars— the roadshows were certainly not the WPA’s venue of choice. All things considered, I think producer George Hirliman simply saw that there was money to be made by exploiting the marijuana scare that was finally seeping out beyond the Texas borderlands and the Deep South, and set himself to the task of beating the likes of Dwain Esper and Kroger Babb at their own game.

After all, the panic was real enough. Though Americans had coexisted peacefully with the Cannabis plant since the 1680’s (in fact, in 1762, Virginia imposed penalties upon farmers who didn’t grow hemp), matters changed radically in the early 20th century. For one thing, the medicinal use of Cannabis extracts had declined steadily after the introduction of the hypodermic needle. (Hemp resin is not water-soluble, and thus cannot be injected directly into the bloodstream.) Meanwhile, the short-lived hashish fad of the 1880’s had been mainly confined to decadent, affluent city-dwellers, and indeed the idea that the hemp plant’s flowers and buds could be turned into cigarettes and smoked for their psychoactive properties seems not to have independently occurred to white Americans at all. (Though the recreational use of Cannabis is attested sporadically throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, the references almost invariably indicate that it was being taken orally in the form of resin-based tinctures. Americans even mostly ate hashish before the Turks who came over for the 1876 World’s Fair showed us how it was done.) But then the new century brought the first major waves of immigration from Mexico and the West Indies, and suddenly here were all these dark-skinned foreigners smoking some exotic, intoxicating weed they called “ganja” or “marihuana.” Nevermind that it was the same damn plant that we’d been getting quietly high on by less efficient means for some 200 years— the different method of delivery and the foreign names meant that it was something new, and the fact that it was being brought to American shores by disfavored minorities meant that it was a menace! At first it was only in parts of the country that had direct contact with the Mexican and Caribbean immigrants that the panic took hold, but in 1930, the Bureau of Narcotics was organized under the leadership of an old soldier of Prohibition named Harry Jacob Anslinger. More than any other single person, Anslinger stoked the fires of marijuana mania, and while he and his supporters never did manage to get a federal ban on pot (that wouldn’t come until the Controlled Substances Act of 1970), by 1937, every state in the Union had some kind of anti-marijuana law on the books. With the help of the tabloid press, the butt-end of the moribund temperance movement, a coterie of medical shysters, and a network of right-wing scare-mongers of every persuasion, Anslinger saw to it that the “devil weed,” the “murder weed,” the “assassin of youth” was hounded into illegality even in jurisdictions where it was never really a problem in the first place. And with a tiny handful of exceptions, the tenor of both the official notices from Anslinger’s office and the stories printed in the popular press was scarcely less mendaciously apocalyptic than that of Reefer Madness. With that sort of thing going on, what fly-by-night exploitationeer could have resisted?

Of course, there was no shortage of cheap-ass movies milking the pot panic, and in point of fact, Reefer Madness was a late arrival on the scene. What makes it so special is that it tries harder than most of its ilk to be a real movie, while attaining little greater success on that front than even the most unabashedly amateurish of the lot. Whether it’s true or not that Gasnier told his cast to hoke it up, that’s certainly what they (and their counterparts behind the camera) did. From the moment Jack’s “kids” arrive at the house to displace Mae’s supposedly older clientele, and the only apparent difference between the two groups is that the latter are dressed a bit more conservatively, we can tell that we’re in for a real treat. The movie can’t seem to go 30 seconds without somebody saying “Gee!” “Golly!” or “swell.” The numerous drug freak-out scenes are simply incredible, especially the one in which Ralph, well on his way to “incurable insanity,” exhorts the piano-playing Blanche to go faster and faster— needless to say, this is precisely opposite to the behavior of any stoner I’ve ever seen in action! I think my favorite thing of all, though, is a recurring minor character, the pothead piano player at the soda fountain where the kids hang out after school. He gets the first freak-out scene in the film, sneaking into a closet to smoke up between songs, and while it’s a bit more subtle than most of what we’ll see over the next 45 minutes or so (not that it comes anywhere near subtle in the absolute sense, mind you), it’s still an awesome sight. More awesome still is the man’s hair— I’ve literally never seen anything like it. His curly, black locks rise from his scalp in a pair of wedge-shaped loaves, turning his part into a sort of triangular valley running down the center of his head. Lord knows how they pulled it off with the styling products of the 1930’s, but I’ll tell you this— just looking at that hair will make your hands feel wet and clammy.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact