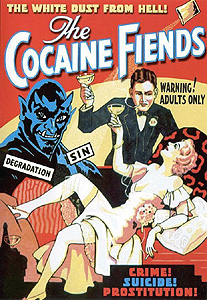

The Cocaine Fiends / The Pace that Kills / Girls on the Street / What Price Ignorance? (1936) -**

The Cocaine Fiends / The Pace that Kills / Girls on the Street / What Price Ignorance? (1936) -**

If we’re going strictly by volume of output, Willis Kent’s main gig during the 1930’s and 1940’s was the production of a string of zero-budget westerns. However, because cheap and shoddy westerns were a dime a dozen in those days (in fact, I’ve had a few cross my path in regard to which that familiar turn of phrase may have been literally true…), it is not for those that the few of us who do so still remember him. For us, his big claim to fame is that, together with Dwain Esper and Kroger Babb, Kent was a leading figure from the earliest days of the underground exploitation movie. In particular, Kent was among the first on the scene with a drug-panic movie, having released his farm-boys-in-big-city-peril flick, The Pace that Kills, as early as 1928. Of course, even the roadshow circuit had little use for silent films by the mid-1930’s, and Kent eventually decided that a remake was in order. Thus it was that The Pace that Kills was reborn in new and more lurid form as The Cocaine Fiends. Just as before, what we have here is an excuse to wallow as deeply in vice and depravity as the censor would allow (which was actually a fair sight deeper than a literal reading of the Production Code should have permitted), thinly disguised as a cautionary message to concerned citizens everywhere. But this second time around, Kent ups the ante by putting the focus initially on a country girl who gets herself, her brother, and eventually just about everyone she meets into all sorts of trouble.

A gangster named Nick (Noel Madison) has been ordered by his boss in the city to expand the mob’s drug trade into the hick towns of the hinterland, and with that in mind, he and an associate are schlepping out into the country with a briefcase full of coke and enough gripes and grumbles to last them the whole trip. Before long, though, Nick notices that they’re being followed, and on the reasonable assumption that the men in the car trailing them are police officers, he has his driver drop him off at a roadside diner while the view between the two vehicles is temporarily blocked by a sharp bend in the road. While the police continue on in pursuit of the car, Nick takes the drugs inside and orders up a chicken dinner from counter girl Jane Bradford (Lois January, from Life Returns), addressing her understandable curiosity about the circumstances of his arrival with a cock-and-bull story about being a traveling businessman trying to escape from a gang of hijackers. Nick and Jane get to chatting while the food cooks, and she tells him about how she’s working at the diner in part to pay the cost of sending her brother, Eddie, to college. Nick, meanwhile, tries to convince her that she’s wasting her life out there in the sticks, and ought to move to the city, where he’s certain some friends of his in the entertainment business could get her a job. Eventually, however, those “hijackers” show up at the diner (having caught, searched, and interrogated Nick’s accomplice to no avail), and Nick is forced to hide in the kitchen until they go away. Jane proves not to be quite so naïve as she appears at first, because she quite rapidly figures out that Nick’s foes are really cops. Nevertheless, she doesn’t rat him out, and in fact seems more interested in him than ever after the police go away and Nick emerges from hiding to finish his meal. And it is during this second conversation that Jane begins her downfall, for she happens to complain of a headache, and Nick tells her he’s got the best medicine going right there in his briefcase.

Jane sees an awful lot of Nick over the ensuing days or weeks or however the hell long it’s supposed to be (you’ll certainly never figure it out from watching the movie), and a sort of openly exploitive, one-way romance— consistently lubricated by Nick’s wonderful “headache powder”— develops between them. Eventually, Nick gets ready to return to the city, and Jane agrees to go with him, with the understanding that the two of them will get married once they arrive. Yeah. Right. Jane ends up as nothing but the latest in a long line of disposable molls, and possibly a prostitute as well. After she’s spent a little while in the city, one of her colleagues clues her in to the nature of that white stuff she’s been sucking up her nose every couple of days since she fell in with Nick, and the collective shame of everything that has befallen her leads her to change her name to Lil. She never writes to her mother anymore, either.

But let’s put Jane/Lil/whatever on the back burner for a bit, and pick up the story of her brother (Dean Benton, from The Return of Chandu, whose later appearance in Willis Kent’s Confessions of a Vice Baron may have come courtesy of footage recycled from The Cocaine Fiends— that’s definitely how Noel Madison got in there, anyway). Eddie, as you may recall, was going to school when his sister met Nick, and a year later, he moves into town himself with the intention of discovering just what has become of her. He gets a job as a car hop at a burger joint, where he befriends his cute, perky coworker, Fanny (Sheila Manners— later known as Sheila Bromley— from Torture Ship and Barn of the Naked Dead). Alas for Eddie, Nick is one of the drive-in’s regular customers, and the gangster keeps Fanny well stocked with blow. She turns Eddie on to the stuff, and before we know it, our homespun hero is getting up to such scandalous shenanigans as going out on dates, having dinner at high-priced nightclubs (on Fanny’s dime— pretty girls always get tipped better, you know), and dancing to swing music. Is it me, or is this movie running through its Progression of Vice act backwards? Before we know it, Eddie has forgotten all about finding his missing sister, he and Fanny are living in sin in a flophouse, and she’s spending the night shift prostituting herself for coke money. Then one of her johns gets her knocked up, she and Eddie have a falling out over the other man’s fetus, and Fanny gasses herself to death in the apartment while her boyfriend runs off and trades up to heroin.

Meanwhile, there’s yet a third parallel plot, this one concerning Dorothy (probably The Black Room’s Lois Lindsay— the credits are unclear below a certain level of billing), the spoiled teenage daughter of a once gigantically wealthy businessman (Frank Shannon, who played Dr. Zarkoff in Flash Gordon and Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars) who has been hit hard by the Depression. Dorothy’s thrill-seeking (which is rather less risibly tame than Eddie’s) leads her to a nightclub called the Dead Rat, which is owned by Nick’s mob. Nick notices the girl, and has her kidnapped. His idea is to reduce the big boss to the level of figurehead by keeping him busy with a demanding young girlfriend, so that he can seize power from behind the scenes; since the chief has always had a thing for feisty blondes, Nick reckons Dorothy for a sure bet. What he doesn’t realize is that the big boss is really Dorothy’s own father, who turned to crime to maintain his family’s lifestyle after the stock market went tits-up in October of 1929. The three plot threads do finally wind their way back together, but when they do, you’ll almost wish they hadn’t.

Well I don’t know about you, but now that I see how cocaine addiction leads directly to such vile and sinful behavior as listening to bebop and going to see really shitty vaudeville acts, I’m staying the hell away. No more “sleigh-rides with the snowbirds”* for me, thanks— from now on, I’ll be getting high on Jesus instead. Actually, the really strange thing about The Cocaine Fiends is the scattershot, mix-and-match portrayal it gives to its fallen characters’ lives of vice. Half the time, Kent and company act like there could be nothing in the world worse than neglecting to keep up correspondence with your mother out in the country, but then out of nowhere, they’ll take a sharp 180, and lay on a real downer of a subplot like Fanny’s descent from party girl to prostitute to abandoned, pregnant suicide. Eddie’s hilariously square “rebellion” ends with him passed out on a bunk in a Chinese-run opium den, and there’s little indication of how the one scenario leads into the other. Dorothy, on the other hand, pursues her own damnation sustainedly, systematically, and with much greater seriousness, yet she winds up happily married to an undercover cop! Meanwhile, the film’s treatment of the business side of dope-peddling is bizarre indeed, in that only once do we ever see anybody paying Nick for a hit. To all appearances, the pushers aren’t in it to make money, but rather expressly to lead the innocent into corruption. It’s this failure of the pieces to fit together into any kind of thematically consistent whole that exposes The Cocaine Fiends as a shameless exercise in salaciousness, instead of the plea for public action promised by its stern and hectoring opening crawl. You’ve got to wonder whether anyone in the audience ever bought the cover story, or whether everybody but the Hays Office and the Legion of Decency was in on the scam from the get-go.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact

* Actual Cocaine Fiends dialogue. Really.