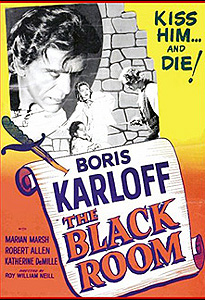

The Black Room/The Black Room Mystery (1935) ***

The Black Room/The Black Room Mystery (1935) ***

Columbiaís 1940ís horror films were frustratingly derivative for the most part, whether they were copying other studiosí lucrative hits or endlessly repeating themselves with Boris Karloffís mad doctor hijinks. The companyís relatively scant contributions to the previous decadeís horror cinema showed more distinctive personality, however. The Black Room, probably the most famous and certainly the most highly regarded of the lot, does admittedly look a lot like the contemporary Universal horrors, set as it is in the same kind of sinister Central European Neverland. But in contrast to those movies, The Black Room eschews both supernatural evil and deranged science to serve up instead perhaps the purest Anne Radcliffe-style gothic of any early American fright film.

Somewhere between Alsace-Lorraine and Transylvania stands the village ruled over by Baron Frederick de Berghman (Henry Kolker, from Bluebeard and The Ghost Walks). We join the action with the baronís wife in confinement giving birth, while the lord of the manor and the local notables gather fretfully in the castleís main hall. The assembled visitors all relax and ready themselves for rejoicing when the doctor announces the successful birth of a male heir, but Frederick himself begins fretting even harder. The future Baron de Berghman did not come into the world alone, you see. He has a twin brother, and twins are reckonned a portent of disaster among the de Berghmans. It was a pair of twins that established the baronial line, and after the younger brother murdered the older in a chamber known ominously as the Black Room, it was prophesied that the house of de Berghman would be extinguished the same way. Frederick believes wholeheartedly in this terrible destiny, but his guests are more skeptical. One of them, a lieutenant of gendarmes by the name of Paul Hassel (Colin Tapley, from Blood of the Vampire and Paranoiac), even goes so far as to propose a way to render the fulfillment of the curse impossible. If the de Berghman line is supposed to die out with twins murdering each other in the Black Room, then why not seal the room up so that no one can possibly kill anybody within its confines? The baron decides that Hassel has the right idea, and orders the Black Room walled in at once.

Decades pass, and the twins both grow up to be Boris Karloff; no, this canít possibly end well. Gregor, the elder twin, assumes the baronial lands and title when Frederick dies, while Anton, the younger, heads off into self-imposed exile in Budapest, where he spends fully ten years. This is because the brothersí relationship sours sharply once their old man is out of the pictureó naturally, the de Berghman curse is a factor in their falling out. Even with a ton of masonry plugging up the Black Room door, Gregor canít shake the suspicion that Anton will do him in if given half a chance, and that suspicion so poisons the atmosphere between them that it becomes untenable for both twins to live under the same roof. Yet despite the conventionally villainous implications of Antonís congenitally gimpy right arm and Baskervillean pet hound, itís Gregor who acquires a reputation as a tyrant and a fiend, to the extent that he eventually finds himself unable to leave the castle for fear of assassins among the villagers. In understandable desperation, Gregor finally writes to Anton, begging him to return home on the theory that things will quiet down if he restructures the local government on a co-seigniorial basis.

Anton is shocked at the depth and breadth of feeling against his brother when he arrives in town. The tavern where he stops to await the carriage from the castle is abuzz with peasants plotting none too secretly against Gregor; someone fires on the coach en route to the de Berghman house; Gregor himself is so paranoically on guard against attempts on his life that he requires Peter the butler (Torben Mayer) to taste the wine he serves to the brothers once Anton is on the premises. In fact, it seems that the only friend Gregor has left is old Paul Hassel, now semi-retired after attaining the rank of colonel (and now played by The Invisible Womanís Thurston Hall). Gregor refuses to talk about the reasons for his subjectsí loathing of him, dismissing the whole business as mere libelous gossip, but a few tantalizing hints come to light when one would-be assassin penetrates the castle itself before being brought low by Antonís monstrous dog. As Gregorís retainers haul the intruder off to what we may presume to be the dungeon, Anton hears him blurt out something about his sister and ďall the other women.Ē

Speaking of women, the one who most has Gregorís eye these days is Thea Hassel (Marian Marsh, of Svengali and The Mad Genius), the niece of the old colonel. Hassel has the de Berghman twins over for dinner at his chateau on Antonís first evening back at the homestead, and while Thea is plainly charmed by Anton, she seems markedly ill at ease whenever Gregor directs his attention her way. Maybe itís just because she is in love with Lieutenant Albert Lussan (Robert Allen, seen many years later in Exorcism at Midnight and Raiders of the Living Dead), one of the officers in the colonelís former regiment, and finds it hard to reconcile the demands of courtesy with the desire not to encourage the baronís advances. On the other hand, maybe itís because she has a subconscious inkling of how close to the mark the villagers are in their assessment of their lordís character. Unbeknownst to her employers, Mashka the Hassel family maid (Katherine DeMille) is having an affair with Gregor, and what happens when their relationship turns sour is both a cautionary example for Thea and the long-awaited explanation for the baronís mammoth unpopularity. Gregor, as it happens, has grown weary of his low-born mistress just as she has reached her limit for swallowing the jealousy inspired by his interest in the Hassel girl. Mashka comes over to the castle some hours after the colonelís dinner party breaks up, and when her efforts at seduction go nowhere, she tries to blackmail Gregor into committing himself to her. The thing is, though, that she has the damnedest time coming up with something credibly threatening to hold over himó and when she finally does find the baronís weak point (Mashka is the only person other than Gregor who knows that the Black Room has a secret back door, and that heís been making use of that door to hide something for quite a while now), the result is not at all what she had in mind. Mashka herself (or whatís left of her, at any rate) now becomes a little piece of the very secret she had threatened to expose.

Inconveniently enough for Gregor, however, Mashka had an ex-boyfriend (John Buckler) among the peasants, and that ex-boyfriend is a relative of Peterís. When Peter finds some of Mashkaís clothes in the castle right after she goes missing, he brings them by the tavern, giving the villagers at last some concrete evidence with which to pin the disappearance of who knows how many women squarely upon their hated lord. Colonel Hassel (who now reveals himself to have a much more ambivalent attitude toward Gregor than we had been led to believe) attempts to fend off the resulting lynch mob so that the case against Gregor can be heard in a legal and orderly manner, but heís just one old man at this point, and his gendarmes are at their barracks, too far away to reach the castle in time to make any difference. In the end, Gregor owes his survival to Anton, whom the villagers have come to respect in the weeks that he has been among them. Gregor offers to abdicate and leave the country, placing all his authority in his brotherís hands, and while Anton himself protests the proposal, it meets with the assent of both Hassel and the mob. Gregor asks only that he be allowed a few days to set his affairs in order before hitting the road. Of course, by ďsetting his affairs in order,Ē Gregor means killing Anton on the sly, dumping his remains down the oubliette in the Black Roomís floor, and assuming his brotherís identity. Then he can cozy up to Colonel Hassel, out-maneuver Lieutenant Lussan for Theaís hand in marriage, and set himself up thereby to add the substantial Hassel property to his own. There are some obvious hazards to this scheme, however. First off, Lussan is hardly apt to greet the emergence of a serious romantic rival with meek acceptance. Secondly, Hassel was close enough to Gregor to see through any but the very best Anton impersonation. Thirdly, that pony-sized dog of Antonís isnít going to be fooled by any disguise Gregor might dream up. And last but not least, thereís the little matter of Antonís last words, gasped out from the bottom of the Black Room pit, whereby he vowed to see the ancient prophecy fulfilledó even if he has to come back from the dead to do it.

Thereís an indefinable stuffiness and artificiality about The Black Room, a ďtrying too hard to be classyĒ quality that it shares with a lot of horrific historical melodramas of its approximate era. Tower of London, Bluebeard, and The Hunchback of Notre Dame all exhibit it to one degree or another as well, and in their cases just as much as The Black Roomís, it looks to have been a conscious bid by the filmmakers to distract the Production Code Administration with a lowbrow impersonation of highbrow theatricality. The pacing in this film is oddly off, too, with a whole movieís worth of plot squeezed into the first 50 minutes, and altogether too many of the remaining 20 spent methodically resetting the board for a similarly hurried conclusion. These things prevent The Black Room from being quite as good as it deserves to be, but this movie remains a sterling example of the correct way to do non-supernatural gothic horror on film. Censor or no censor, it doesnít shy away from a single bit of Grand Guignol business. Even when the enforced propriety of the Hays Code requires that something happen offstage, writers Arthur Strawn and Henry Meyers, together with director Roy William Neill, make it perfectly plain what the camera has missed. Nor do they show any fear of formula, embracing without shame all the garish appurtenances of the genreó the morbid castles, the family curses, the diabolical noblemen, the heroes condemned for crimes they didnít commit, the heroines tricked and coerced into marrying villains, the evil twins substituted for good, etc. And most importantly, they do it all with a great deal of style and wit, helped immeasurably by cinematographer Allen G. Siegler and art director Stephen Goosson. One Hollywood horror movie castle generally looks much the same as another, but the sets in The Black Room exhibit such attention to detail, and the camera exploits that detail so cleverly, that there winds up being little comparison, visually speaking, between this movie and most others of its type. I especially like Antonís death scene, in which his plunge into the oubliette is shot from the bottom of the pit. Not even the woefully obvious dummy taking the fall can ruin that shotís impact. Similarly, Sieglerís astutely chosen camera angles are integral to the success of the sequence wherein a fortuitously timed glance at a mirror tips Colonel Hassel off to Gregorís grand deception.

Finally, I would be remiss if I concluded this review without saying a few words in praise of Boris Karloff and Marian Marsh. Karloffís performance here elevates what might have been a mere gimmickó his casting as both of the de Berghman brothers, with its attendant invitation to all manner of camera trickeryó to one of the richest displays of acting prowess in his 40-some years on the screen. Look closely at The Black Room, and youíll see that it gives Karloff not merely one of the double roles that have figured so prominently in horror cinema since that first version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde in 1908, but something very close to a triple: Karloff portrays Anton, Gregor, and Gregorís impersonation of Anton. The drastic differentiation that he achieves between Gregor and Anton is impressive enough (Gregor even lacks the notorious Karloff lisp!), but Gregorís very slight errors in copying Antonís mannerisms are what really gets me. Most of them are so minute that I honestly canít put my finger on them, but one that I did catch specifically has to do with Antonís paralyzed right armó Karloff consistently holds the ďdeadĒ hand just the tiniest bit differently as Anton than he does as Gregor pretending to be Anton. As for Marian Marsh, she makes for an extraordinarily vibrant heroine, even if the script gives her no more to do than any other damsel in gothic distress. She gives the impression, when Gregor maneuvers Thea into submitting to a marriage she doesnít want, that Theaís legally imposed powerlessness to do anything about it on her own behalf troubles her at least as much as the undesired betrothal itself. She also makes Thea one of the very few gothic heroines who seem like theyíd be worth the bother of all the conniving expended on them, even without her uncleís property looming in the background. Heaven knows The Woman in White and The Virgin of Nuremberg could have used somebody with Marshís spirit to play the female lead.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact