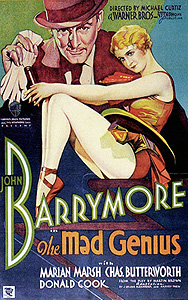

The Mad Genius (1931) **½

The Mad Genius (1931) **½

When a film earns a lot of money, it’s only natural for the people who made it (or, for that matter, their competitors) to try to repeat that success. Today, there are three basic strategies in use for following up a successful movie: the sequel, the remake, and the rip-off (the latter broadly construed here to encompass the possibility of producers ripping off themselves as well as each other). There was a fourth technique employed in olden days, however, one that seems to have been tacitly deemed too obvious for “sophisticated” modern audiences. Back in the 30’s, it was not unknown for the cast and crew of a well-received movie to be put to work a second time on a virtually identical picture that would effectively act as sequel, remake, and rip-off all in one. Warner Brothers’ The Mad Genius is one such film. In an effort to recreate the success of Svengali earlier in the year, it reunites screenwriter J. Grubb Alexander and art director Anton Grot for another tale of a diabolical mastermind living vicariously through a young artist whom he cruelly dominates. It also brings back the stars (and many of the supporting players) of Svengali to reprise their roles in all but name, albeit with one major difference. This time, the enslaved artist is a young man, so Marian Marsh is shifted a bit to the side to play his only slightly less put-upon girlfriend.

A title card tells us that the setting is a “peasant village” in “Central Europe,” “fifteen years ago.” To judge from certain unobtrusive hints in the dialogue and scenery, I’d say “Central Europe” is probably the part of Poland that belonged to the Russian Empire until the end of the First World War. There’s a carnival in town just now, and among the attractions is a puppet theater operated by Ivan Tsarakov (The Invisible Woman’s John Barrymore, who even looks like a somewhat less unkempt version of the character he played in Svengali) and his slightly dim-witted partner, Karimsky (Charles Butterworth). It’s no coincidence that Tsarakov has his marionettes dancing; his mother had been a ballerina, and he would have liked nothing better than to be a dancer himself. Tsarakov was born with a clubfoot, however, and just walking is difficult enough for him. That goes some way toward explaining the puppeteer’s peculiar reaction one night when his sole customer (The Phantom Empire’s Frankie Darro) has a noisy, violent altercation with his father (Boris Karloff, seen here literally a matter of weeks before his star-making turn in Frankenstein). The boy had run away from home, evidently for fear of being drafted into service as a drummer or some such thing in the by now plainly doomed Russian army, and Dad has come to collect him, armed with a horsewhip. As the boy ducks and dodges around Tsarakov’s tent and its immediate vicinity, the puppeteer remarks to Karimsky about what a fine dancer he’d make. Tsarakov gets a funny look on his face when he makes that observation, and he unexpectedly comes to the lad’s rescue, giving him a place to hide and feeding his enraged father a bunch of bullshit to deflect his attention far away from the carnival.

Fifteen years later, in Berlin, young Fedor Ivanoff (now played by Donald Cook, of The Ninth Guest) is indeed a dancer, heading up the ballet troupe for which Tsarakov has traded in his old puppet theater. He’s just as good as Tsarakov imagined he’d be, too, pursuing his art with all the single-minded dedication his rescuer and mentor could instill in him. Even a truly devoted artist needs to unwind occasionally, though, and Tsarakov has consequently made a policy of choosing his ballerinas with one eye toward his surrogate son’s sexual tastes. The company’s current prima, Nana Karlova (Marian Marsh, from The Black Room and Murder by Invitation), is the latest product of Tsarakov’s double-edged recruitment strategy, and she seems to suit Fedor better than all of his previous partners combined. Nor is Fedor alone in his appreciation for the girl, for a regular patron of the ballet by the name of Count Robert Renaud (Andre Luguet, who played in Le Spectre Vert, MGM’s French-language export version of The Unholy Night) is most disappointed when Tsarakov informs him that Nana has been reserved for Fedor alone. What Tsarakov doesn’t realize yet— and what will make him reconsider his stance on both Nana and Renaud when he finds out— is that his two star dancers aren’t merely banging each other in between rehearsals. Fedor and Nana are in love, and hope to marry someday. The reason Tsarakov is so horrified when he figures that out is that he firmly believes that an artist must be wedded to the Muse alone; love is a distraction that a creative personality can ill afford, while women are untrustworthy, destructive creatures who can be approached safely only in the context of short-term exploitation. Fedor is living the dream that Tsarakov’s deformity put outside of his own reach, and Tsarakov will be damned if he lets some bimbo get in the way of that!

Clearly, the only thing for it is to split the couple up somehow, and the devious scheme whereby Tsarakov aims to do it reveals a level of utter amorality that might have given Svengali himself pause. First, he dictates a letter to Karimsky, expressing doubt about Nana’s ability to do justice to the role for which she is currently rehearsing, and suggesting that it go instead to someone older and more experienced, like Sonya Preskoya (Carmel Myers, another returning Svengali player), an old girlfriend of Tsarakov’s. Then he brings in his stage manager, Sergei Bankieff (Luis Alberni— still another one!), and orders him to sign the letter, as if he had sent it to the boss. Bankieff protests. He has nothing but respect for Nana’s abilities, and considerable personal affection for her as well; under no circumstances will he participate in such underhanded dealings against her. Sergei is a drug addict, though, and his honor is only as good as his certainty of getting another fix. Tsarakov, meanwhile, is Bankieff’s supplier, and when he threatens to toss the stash he keeps for Sergei in the furnace, the stage manager cracks and miserably consents to sign the forged letter. Next, Tsarakov telephones Count Renaud, and suggests to him that he renew his efforts to court Miss Karlova. Finally, Tsarakov summons Nana herself, and presents her with the supposed letter from Sergei. Tsarakov is ostentatiously regretful, but says there’s nothing he can do at this point. He trusts Sergei’s judgement implicitly, and if Sergei says Nana is in over her head, then Tsarakov must accept his verdict. Still, Nana needn’t fret for her future. She is, after all, a superb dancer, technically speaking, and there are, after all, plenty of roles in ballet for which youth, beauty, and physical stamina count for more than maturity of interpretation. Tsarakov will be happy to keep quiet about Bankieff’s misgivings, and to give Nana his warmest recommendation for whatever she chooses to do after separating from his company. As for her budding romance with Fedor, Tsarakov assures her that she has over-interpreted the lad’s interest in her, and that she will only be inviting emotional injury to herself if she persists in accepting his courtship; she’d be much better off with Robert Renaud, who really is smitten with her. What Tsarakov doesn’t realize is that Fedor is standing right outside the office at the time. He overhears Tsarakov trying to steer Nana toward Count Renaud, and he bursts in to call bullshit on the whole business. Fedor does love Nana, and he proclaims that he’d much rather have her than the career his surrogate dad has plotted out for him in such meticulous detail. He and Nana elope at once for Paris, leaving Tsarakov without any star performers at all.

For a while, Tsarakov is devastated by Fedor’s rejection, and sinks into drunkenness and dissolution. With his artistic dreams in ruin, he even takes up again with Sonya, and apparently moves into her apartment. But then Karimsky happens to mention that he found Fedor’s contract with Tsarakov while going through some old papers, and the wily old devil remembers something that had slipped his mind during the heated altercation over Nana. That contract he concluded with Fedor was an exclusive one, binding the boy to Tsarakov for eight years. In other words, Tsarakov is in a position to force his protégé to choose between dancing for him or having no ballet career at all. Tsarakov knows Fedor too well to assume that such crude blackmail will be effective, but he also knows Nana well enough to recognize the leverage he could exert by exploiting her feelings instead. After all, by standing up to Tsarakov, Fedor is sacrificing his lifelong professional ambitions in exchange for Nana’s happiness. Surely it would be no trouble for a man as slippery as Tsarakov to play up that angle while obscuring the point that Fedor’s relationship with Nana is a major source of happiness for him as well.

The really curious thing about The Mad Genius is that for all its conspicuous similarities to Svengali— same cast, same creative team apart from director Michael Curtiz taking over from Archie Mayo, same central conflict and even many of the same key plot points— it manages to belong to a different genre from its model. Though the fit is a little loose in some places, Svengali is most readily intelligible as a horror film. The Mad Genius, on the other hand, is merely a melodrama with some faint hints of Expressionist styling in the lighting and set design, and an exaggeratedly diabolical villain. Unlike Svengali, Tsarakov has no powers beyond an exceptionally keen eye for other people’s weaknesses, and the thrall in which he holds Fedor and Nana is a purely psychological one. Until the sudden and rather intrusive Grand Guignol conclusion (brought on by Sergei’s dope habit in a manner worthy of Dwain Esper or Kroger Babb), there is no violence of any kind. And even the look of the film is much more conventional than that of its Germanically nightmarish inspiration, despite an emphasis on unusually immersive sets and a few scenes that are lit and composed so as to present Tsarakov as a nearly Satanic personage. It may have been that retreat from the eeriness of Svengali that doomed The Mad Genius at the box office, where its limp reception reportedly helped convince the Warner Brothers leadership that $450,000 a year was more than John Barrymore was worth. Barrymore is as commanding as ever, and the people behind the camera again demonstrate a modernity of technique far in advance of the norm for 1931, but it’s easy to see why those who came to The Mad Genius looking for more of what approximately the same team had given them some months before would have been badly disappointed.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact