Svengali (1931) ***

Svengali (1931) ***

Warner Brothers’ earliest contribution to the first Hollywood horror boom is often overlooked, perhaps because it is so easily debatable whether it properly qualifies as a horror film. The earlier silent movies adapted from George DuMaurier’s Trilby had reportedly been handled as relatively straightforward dramas with just a hint of the gothic occult, and to a certain extent, that might be said of Warner’s Svengali as well. But Svengali does one thing very differently from its predecessors, and it is this, in my mind, that earns it its place in the horror genre— whereas the focus in earlier Trilby movies had always been upon the imperiled heroine, Svengali puts the villain at center stage, and allows no question but that there is something more than natural about the hold he maintains over the object of his twisted affections. This amounts to an almost complete inversion of earlier takes on the story, and it is thus most apt that the villain’s name should supplant the heroine’s as the title of the film.

In fact, Svengali (John Barrymore, from The Invisible Woman and the best-known silent version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) is the first character we meet. He is a pianist and composer from Poland, living with a sidekick called Gecko (The Man from Beyond’s Luis Alberni) in Paris, where he supports himself with a combination of musical tutoring and open parasitism. And as we are about to see, he sometimes uses the one as a foundation for the other. One of Svengali’s pupils is an attractive young woman (Carmel Myers), whom he has spent at least as much effort seducing as teaching to sing. So successful has Svengali been in the former enterprise that the woman has actually left her husband in order to be with him. This she reveals with great effusiveness at her next lesson, but Svengali doesn’t take the news quite the way she was expecting. Sure, he wanted the girl for himself, but he was really more interested in gaining access to whatever property and/or liquid assets she could finagle out of her husband in a divorce settlement. Instead, she has just up and split, handing herself over to Svengali without two sous to rub together, and the conniving old bastard is furious. He sends his excessively trusting student packing, and the next thing we hear, the police have pulled her drowned body from the Seine. There’s something fishy about this scenario, though. While the dead girl was cowering her way out through Svengali’s front door, she kept repeating a very curious plea: “Take your eyes off me! Please— take your eyes off me!”

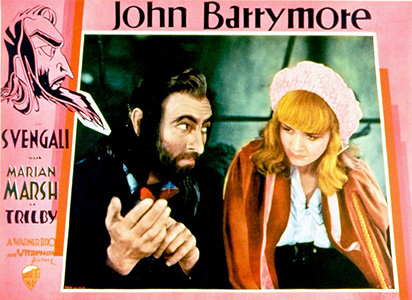

The next day, Svengali and Gecko pay a visit to their “English friends,” Taffy (Lumsden Hare, from Black Moon and The Four Skulls of Jonathan Drake), Laird (Donald Crisp, of The Uninvited and a different Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde), and Billie (Bramwell Fletcher, also seen in The Undying Monster and The Monkey’s Paw), in the hope of scoring some breakfast. The three Brits have better things to do, however, for they’re all painters, and they have a model coming over this morning to sit for them. And more importantly, they’re all sick to death of Svengali’s mooching, and after hiding their money, Laird and Taffy forcibly bathe Svengali and then rush out to summon the neighbors to enjoy the spectacle. (It would appear that Svengali is not exactly known for his impeccable personal hygiene.) But the joke is on them, for while they’re out rounding up spectators, Svengali is helping himself to Taffy’s best suit and the coin purse Laird hoped to conceal in one of its pockets. Furthermore, when the model shows up, Svengali gets to enjoy a moment alone with her. Her name is Trilby O’Farrell (The Black Room’s Marian Marsh, who would go through this whole routine again later in the year, when Svengali was all but remade as The Mad Genius), and she is exceedingly cute, impishly self-assured, and possessed of an extraordinary singing voice. It’s the latter that really gets Svengali’s attention, and in the days to come, he sets himself to scheming over how to turn her talents to his advantage.

Svengali drops in on the Brits quite a lot after his meeting with Trilby, hoping to catch the girl modeling for them. It might seem at first as though the romance developing between her and Billie could pose an enormous obstacle to Svengali’s designs, but he’s got a trick up his sleeve which Billie has no chance of counteracting. The reason the would-be singer in the opening scene was so insistent that Svengali stop looking at her was that the pianist wields preternatural powers of hypnosis and mental domination— to look into his eyes is to surrender to his will, and we may safely assume that the doomed pupil’s suicide was not precisely her idea. When Svengali finally succeeds in intercepting Trilby, she is complaining of a terrible headache, and he uses Trilby’s throbbing temples as an excuse to hypnotize her. Naturally, “no more headache” is not the only post-hypnotic suggestion Svengali plants, and from this moment forward, Trilby will be inextricably under the mesmerist’s power. When Billie later walks in on Trilby posing nude (now that’s what I call pre-Code!) at a nearby art school, leading to a jealous blow-up between the two of them, Svengali persuades her that she has no future with Billie, and then fakes her suicide. Billie, Taffy, and Laird are so busy fretting over the implications of Trilby’s empty apartment and the discarded clothes found by the police on the riverbank that they never notice the obvious connection when Svengali and Gecko split town the same day.

Five years later, all of Europe is in ecstasy over the conductor-composer Maestro Svengali and his wife, the beautiful and phenomenally talented soprano who is the star of his show. I surely do not need to tell you that Madame Svengali is in fact the supposedly deceased Trilby O’Farrell. When the tour rolls into Paris after taking Berlin, Vienna, and St. Petersburg by storm, Billie, Taffy, and Laird go to see it— mostly out of astonishment that their sleazebag former neighbor has unaccountably made something of himself— and thus it is that Billie discovers that his lost love is not nearly so lost as he had been led to believe. Furthermore, a brief interaction between him and Trilby on the street in front of the opera house convinces Billie that her relationship with Svengali rests upon some sinister and possibly unnatural basis. Billie becomes Svengali’s implacable enemy, hounding him all over Europe in an obsessive quest to expose just what manner of hook he has in the girl.

Among the 1931 Hollywood horrors, Svengali is exceeded, so far as I’ve seen, only by Rouben Mamoulian’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. John Barrymore should have played villains more often. J. Grubb Alexander’s script continually peels back layers of Svengali’s character, making him seem more and more dangerous each time, and Barrymore plays to that approach very skillfully. At first it seems that he’s merely a creep, unpleasant to be around but mostly harmless if you can keep him away from your wallet and don’t let him talk you into anything. But then he hypnotizes Trilby, suddenly shedding a new and altogether more ominous light on everything we’ve seen up to that point. The singing student in the opening scene was not just a trusting fool; her drowning was almost certainly more than the desperate act of a heartbroken woman who has just learned that she’s thrown away a perfectly comfortable existence for nothing; even Taffy’s comment about Svengali’s skill at persuading people to part with their money acquires a sinister connotation which it hadn’t had before. And once his true colors are revealed, you get the feeling that Svengali has made himself repellant by design, hiding his tremendous power behind a smokescreen of small-time crookedness. Barrymore makes this work with a commanding demeanor that he can switch on and off like an electric light— he hardly needs the glowing-eyes effect that the film uses to represent the exercise of his hypnotic abilities. More remarkable still is Barrymore’s success in selling the character’s final transformation at the movie’s end. Having risen from a figure of almost comic sleaze to one of diabolical menace, Svengali becomes at the last someone we can halfway feel sorry for, as it becomes increasingly obvious that he has defeated himself by falling in genuine love with Trilby only after he has exploited her far too much ever to be loved in return.

Svengali’s effectiveness as horror also owes much to the production design. Paris as imagined by art director Anton Grot has less to do with the real thing than it does with Hans Poelzig’s Prague in The Golem. The city is a nightmarishly cockeyed heap of twisted and misshapen buildings, linked together by a labyrinthine warren of chaotically winding, tunnel-like streets. The key scene in which Svengali activates his hypnotic control, and makes Trilby come to him in the middle of the night, is one of the most striking set-pieces in early-30’s horror cinema, and makes absolutely optimal use of Grot’s magnificent miniature sets. Beginning with a tight closeup on Svengali’s glowing eyes, the camera rushes backward through the hypnotist’s bedroom window and across the tilting and disordered rooftops until it reaches Trilby’s bedside. Few of this movie’s better-known contemporaries feature anything comparably eye-catching.

Unfortunately, there are nevertheless a few important things about this movie that don’t quite work. Although I understand and indeed commend the reasoning behind them, the shifts in mood between the humor of the first act, the overhanging doom of the second, and the sympathetic pathos of the third, are somewhat jarring. The jokey stuff early on also isn’t especially funny, though it does score major points for not being driven by people running around in circles, shrieking at the top of their lungs, and slapping each other upside the head. Some modern viewers might also be turned off by the movie’s implicit antisemitism. At no point is Svengali ever identified specifically as being Jewish, but his appearance, accent, and initial behavior are all unmistakably drawn from the era’s most negative stereotypes about Jews, and with a less nuanced performance than the one Barrymore provides, the characterization would be exceedingly distasteful.

The final point I want to raise about Svengali concerns the handling of his mental powers. Though it is described as hypnosis by all of the other characters, and though Trilby’s behavior while entranced is typical of the way mesmerism is generally portrayed in the movies, Svengali’s hold over his victim plainly stems from something much more exotic than a mere altered state of consciousness. Svengali is able to link his mind with Trilby’s even from all the way across the city, and when he takes control of her, it is a matter of his will crushing and subsuming hers by brute mental force. Consequently, Svengali can be seen as a distant antecedent of movies like Scanners and The Power, and even more interestingly, it resembles those films in positing a physical cost for the employment of psionic abilities. It weakens Svengali whenever he uses his hypnotic gaze, and by the third act, the strain of maintaining his mental grip on Trilby for years on end has left him shockingly enfeebled. I haven’t yet managed to get my hands on George DuMaurier’s novel, but I am very curious to see whether this little wrinkle to the story was J. Grubb Alexander’s invention, or if it dates all the way back to the book. Either way, somebody was decades ahead of the game.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact