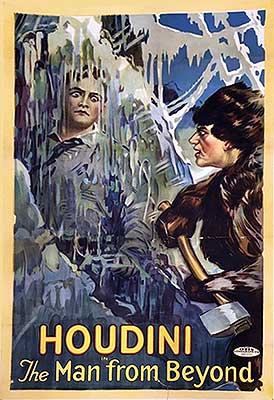

The Man from Beyond (1922) *˝

The Man from Beyond (1922) *˝

The entertainment landscape of the late 1880’s was so different from today’s that I can barely wrap my mind around it. No internet, no video games, no Blu-Rays or DVDs or VCRs, no television, no comic books, no radio, no recorded music, no paperback novels. Even pulp magazines were a few years in the future, although the more expensive glossies had been a going concern for some decades. Professional sports as we know them and what we would now call standup comedy were in their respective infancies. Sheet music was a mass medium rather than a niche market. Variety theater was blossoming into vaudeville. There were blackface minstrel shows and Wild West shows and touring museums of exotic artifacts that were occasionally even real. Circuses were enjoying last phase of their heyday, as were magicians, mesmerists, and other showmen of the uncanny. City folk had music halls and operetta, and the “legitimate” stage wasn’t yet just for those who thought of themselves as sophisticates. Country people went to medicine shows to watch quack doctors fraudulently demonstrate the power of their miracle cures, and attended revivals as much out of desire to have something to do as from concern for the state of their eternal souls. People didn’t outgrow carnivals at the age of thirteen, not least because any carnival worth a damn would be accompanied by a sideshow promising things that there was simply no other way to see. So when a poor rabbi’s son by the name of Erik Weisz got bitten by the showbiz bug in his early adolescence, it was only a little bit weird for him to seek fame by wriggling out of increasingly baroque systems of restraints and inviting men from the audience to come up onstage and punch him in the stomach. Indeed, the only thing truly remarkable about Weisz’s success as a stunt performer was how much of it he ultimately attained. Mind you, before he could become famous for anything, that name had to go. Exit Erik Weisz, and enter Harry Houdini.

Houdini had a short life, but a long career— especially once you figure how long one can reasonably expect to earn a living by being handcuffed, tied up, locked in a safe, and dumped into a vat of water. In a way, though, his longevity was precisely his problem toward the end, because by the 20th century’s teen years, some of those modern forms of entertainment I mentioned at the beginning of the review had arrived on the scene, and were cutting into the business of more old-fashioned showmen. The most threatening of the upstart amusements was the motion picture. Movies offered almost limitless potential variety to a public that craved the novel and the exotic. They could simulate any setting that their creators could imagine, tell any kind of story, display any manner of spectacle. They could play tricks to confound the greatest illusionist, present marvels from abroad to outdo any traveling exhibition of curiosities. And although it would be some years yet before the full significance of this point was appreciated by either filmmakers or theater owners, the movies never had an off night. If you liked what you saw, you could come back tomorrow and see it again just the way it was the first time. A lot of showmen tried to fight the cinema. They supported censorship campaigns, lobbied for punitive zoning rules, publicly denigrated the talent that went into film production, cynically echoed the sentiment when professional killjoys impugned the morals of both the people within the new industry and their customer base. Houdini, however, realized that the flickers were here to stay, and decided to join what he couldn’t see a way to beat. If movie stars were going to become the world’s foremost entertainers, then Houdini would simply have to become a movie star.

His first effort in that direction, released in 1919, was a fifteen-chapter serial entitled The Master Mystery. It had an ingenious hook. Each chapter save the last one would end with Houdini’s character trapped by his enemies, and the next one would begin with him escaping from his latest fix without benefit of any camera trickery whatsoever. With the dawning of the 20’s, Houdini graduated to features like Terror Island and Haldane of the Secret Service, and he continued sporadically in the business nearly until his untimely death in 1926. Houdini never enjoyed much success on film, however. Partly that was because he couldn’t quite get the hang of acting. Partly it was because the scripts written for him were stodgy and out of date at a time when the art of the motion picture was maturing almost too rapidly to follow. Partly it was because his natural charisma, honed for the variety show stage, just didn’t translate to the screen, leaving him looking awkward and uncomfortable whenever he wasn’t actively performing a stunt. But the biggest thing holding Houdini back as a movie star was a fundamental flaw in the premise of his film career. Houdini’s claim to fame was that he really did escape from those deathtraps, but on film, there was no significant visible difference between his genuine escapes and the ones Pearl White and Helen Gibson used to achieve every week via sleight of camera. It took a practiced eye to note the absence of cutaways and other tricks in his movies, but practiced eyes were as yet in short supply. The Man from Beyond, Houdini’s third feature film, amply demonstrates all the aforementioned ills, and wanders obliviously right past the most interesting implications of a terrific premise while it’s at it.

The expedition of Arctic exploration led by Dr. Gregory Sinclair (Ewin Connelly) is going very badly. Sinclair’s ship has been trapped in the ice since winter began, and the crew’s stores of food are nearly exhausted. The only thing left to do is to harness up the sled dogs, and set off southward across the ice in the hope of encountering a friendly Inuit band. That doesn’t go well, either. Within a few days of trekking, Sinclair himself and a soldier of fortune named François Duval (Frank Montgomery) are the only men left alive, and the scientist looks unlikely to last much longer. When Sinclair finally collapses, too weak to regain his feet, Duval invokes the Law of Nature, and forges on without him.

Don’t be too quick to dismiss Duval as a scoundrel, though. Not long after abandoning Sinclair, the mercenary comes upon another ship frozen into the pack ice. Obviously it won’t be getting him home any more than his own stricken vessel, but its hull looks intact enough to provide shelter from the raging Arctic winds, and its hold might contain usable provisions. That slender lifeline is enough to turn Duval back around to retrieve Sinclair, and the latter man recovers with surprising speed once he’s out of the elements. The two explorers make a remarkable discovery, too. Encased in the thick ice encrusting the upper deck is the body of a man (Houdini) who the ship’s log suggests may be Howard Hillary. Hillary was a chronic discipline problem whom the captain had confined below decks not long before he and the crew were forced to abandon ship in a tempest a thousand miles distant from the vessel’s current position. Sinclair finds Hillary’s diary, too, which sheds more light on the situation. Evidently his enmity with the captain revolved around two of the passengers, Milt Norcross and his daughter, Felice (played in flashback by The Ghost of Granleigh’s Yale Benner and Jane Connelly). Howard fell in love with Felice, but the captain (Luis Alberni, from Svengali and The Mad Genius) delighted in interfering with their courtship, perhaps because he too had designs on the girl. It’s all pretty much academic at this point, though. The log and the diary are each dated 1820, meaning that Howard Hillary has been frozen solid for over 100 years.

Duval doesn’t care about any of that. He’s a practical man, and when he looks at Hillary entombed in the ice, he sees not a victim of unjust fate, but an enticingly large quantity of preserved meat on the hoof. As soon as he satisfies himself that the supplies remaining in the hold are inadequate for his and Sinclair’s needs, he sets about chopping Hillary free to become their next couple weeks’ worth of meals. Incredibly enough, however, the frozen man turns out to register just the faintest vital signs. Faced with this opportunity for an unprecedented medical triumph to make up for the failure of his real mission, Sinclair puts the kibosh on eating Hillary, and busies himself trying to revive him instead. The patient is understandably bewildered when he eventually comes around, and it costs Sinclair and Duval considerable effort to control him at first. They do ultimately get him settled down enough to explain to him his situation, but under the circumstances, Sinclair thinks it wise to elide the little detail of just how long Hillary has been in suspended animation. There’ll be time enough to tackle that if they ever get back to civilization.

Incidentally, don’t hold your breath waiting for an explanation of how Sinclair, Duval, and Hillary manage that, beyond that it takes them three months. One scene, they’re stuck fast in the Arctic ice, and a single intertitle later, the explorers are taking Hillary to see Sinclair’s friend and colleague, Dr. Crawford Strange (Albert Tavernier). They happen to arrive right in the middle of the wedding of Crawford’s daughter, Felice, to yet a third scientist called Gilbert Trent (Arthur Maude, from The Wraith of Haddon Towers). Those of you who’ve noticed that the bride shares the name of Hillary’s love interest from a century ago will not be surprised to see that she’s also played by the same actress. Chances are you’ll have foreseen the whole shape of the story to come, too. That’s right— Hillary, having not yet been told that his Felice has been dead for some 50 years, tries to interpose himself between Felice Strange and Dr. Trent. And because the current Felice is in fact the reincarnation of the one from the 19th century, she finds herself uncannily attracted to the man from the ice. Conveniently, Trent quickly reveals himself as an underhanded asshole and a budding criminal, so Felice need feel no qualms about chucking him overboard in favor of Howard. Alas, though, that just inspires Trent to direct his criminality toward the trans-temporal couple, with the aim of forcing the girl back to the altar with her original groom. Naturally, Trent’s campaign of dirty tricks will afford Houdini plenty of opportunities to perform death-defying stunts and to show off his famous escape artistry.

Actually, let me rephrase that. Although there are plenty of stunts involving climbing, swimming, dangling over precipices, and so forth, there’s only one escape of the sort one expects from Houdini, when Trent arranges to have Hillary locked up in an insane asylum. Obviously The Man from Beyond would have worn out its welcome pretty quickly if it had relied as heavily on escapes as The Master Mystery, but scaling down to just one is a major letdown. I mean, he’s Harry Houdini, for fuck’s sake. He has to have known that nobody was watching this movie to see him act! At the same time, though, even that one escape is sufficient to show that the movies were the wrong venue for exhibiting Houdini’s talents. Simply put, the technique adopted to prove that Houdini really was freeing himself from that straitjacket unaided— long shot showing the whole room, no cuts or camera movements— is uncinematic and visually boring, yet also fails to achieve the desired aim. Intellectually, we may know that Houdini’s escape from the jacket is for real, but we also know how easy it is to fake things for the camera. And this particular camera is too far away from the action to convey how specifically Houdini is performing the feat. The effect is a genuine escape that looks much less impressive and exciting than the simulated ones that had been commonplace in adventure serials for ten years already.

I make that serial comparison advisedly, because it points to a far more pervasive problem with The Man from Beyond. The core writing assumption of the chapterplays— that characterization, motivation, and even basic coherency don’t matter so long as the plot is kept in a state of constant agitation— also underlies this movie, to the degree that it resembles nothing so much as an injudiciously handled feature-length cutdown of a serial. Dr. Trent gains and loses the upper hand again and again with nearly clockwork regularity, but none of the back-and-forth between him and Hillary ever adds up to anything like a unified arc of rising action. That’s acceptable in a serial, where you’re not supposed to watch more than one cycle of table-turning at a time, but in a feature it not only becomes repetitive fast, but also leads the viewer to suspect that there might not be any real point to the proceedings.

The Man from Beyond looks remarkably lazy about setting up its individual mini-conflicts, too. I say “looks” because it’s possible that as many as eight minutes of footage were missing from the print I saw, which ran 66 minutes instead of the 74 claimed by the Internet Movie Database. On the other hand, it’s equally possible that the discrepancy is merely an artifact of differing frame rates. Either way, The Man from Beyond as I saw it neglects to portray key plot developments like the abduction of Dr. Strange by Trent’s agents, and makes no serious effort to depict the passage of significant spans of time. There isn’t even a scene transition when the kidnapping occurs. One moment, the cops are rousting Hillary from the wedding at Dr. Trent’s insistence, and the next, Felice is talking to Sinclair about how her father never returned from some errand or other. What errand was that? It’s difficult to say. I suppose it could have been the trip to the asylum that Strange was promising to make on Hillary’s behalf after the arrest (which would explain why Felice is still wearing her wedding gown when she first mentions her father’s disappearance), but that doesn’t seem to allow enough time for Trent to arrange the abduction. Also, neither Felice’s worrying nor Trent’s bullshit cover story makes any sense unless Strange has been gone a lot longer than we can account for by assuming that he was snagged immediately after leaving the aborted wedding. Of course, other aspects of that conversation are equally unintelligible unless Strange was shanghaied on his own doorstep before he could reach the asylum, so I give up. And if you really want to talk about missing time, check out the scene where Hillary and Sinclair finally locate the missing man. A year is supposed to have elapsed since the kidnapping, but Strange’s rescuers are still wearing the same suits they’ve had on all along! Meanwhile, there’s a whole subplot involving a femme fatale (Nita Naldi, from Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde) hired by Dr. Trent to neutralize Hillary, which might as well have been spliced in from some other movie for all the impact it ever has on anything.

The Man from Beyond’s worst failing, though, is its determination to ignore its own premise. You’d think that a man from 1820 would have a difficult time adjusting to life in the 20th century. For that matter, you’d think it would be impossible for him not to notice almost at once that he’d been out of action for a long time. Try to imagine the homecoming that the movie abstains from showing us. Even if Sinclair, Duval, and Hillary had fortuitously been picked up by a wooden-hulled sailing ship (quite a few of which were still in active commercial service in the 1920’s), they would eventually have reached a port crammed with steel-hulled freighters, diesel-powered tugs, and giant transoceanic liners. After docking, they would have made their way through a city where empire waists and tailed topcoats were nowhere to be seen among the crowds of pedestrians, where automobiles and cable cars had all but replaced horse-drawn carriages, where immigrant dockhands spoke foreign languages Hillary had probably never heard in person before, and where there wasn’t so much as a single black slave. They would then have boarded a train to reach Sinclair’s home on the outskirts of town, for which the scientist would have paid their fare with coins almost unrecognizable to Hillary. And Sinclair’s house would have been furnished with conveniences (albeit admittedly not that many of them) that hadn’t been invented yet when his guest embarked all those years before. Howard Hillary would have to be the stupidest man alive not to know that something was up! Now as I said, The Man from Beyond dodges the issue somewhat by not showing the protagonists’ arrival in New York or wherever, but then it turns right around and raises it again by having them travel to the Strange mansion by automobile. Still, Hillary never experiences the briefest moment of disorientation, awe, or culture shock, nor does his century-old value system ever lead him to behave differently or to reach different conclusions than the characters who are living in their own era. Indeed, the only purpose to which this movie ever puts Hillary’s time displacement is to set up a plug for reincarnation, which was something of a hobby horse for Houdini at the time. (Houdini had an intriguing relationship with his era’s craze for spiritualism. Although he prefigured James Randi by putting his knowledge of trickery to use debunking phony mediums and the like, he did so as a true believer, seeking to weed out the fakes to make talking to ghosts an honest and respectable profession.) At one point, Hillary even hands Felice one of Arthur Conan Doyle’s spiritualist pamphlets in the hope of convincing her that she has the same soul as the girl he loved 100 years ago. About the one thing I can say in favor of this approach is that it inadvertently opens the door to some interesting alternate interpretations of the conclusion. We’re supposed to take what happens in the final shot as a happy ending, but seen through modern eyes, it could just as easily be the beginning of a period-piece Exorcist knockoff instead.

This review is part of “Don’t Quit Your Day Job,” the B-Masters Cabal’s... well, maybe “tribute” isn’t quite the right word... to those who aren’t content with just one form of stardom. Click the link below to read my colleagues’ thoughts on the athletes, musicians, escape artists, and so forth who cast their gaze toward Hollywood, and say, “Shit, I can do that!”

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact