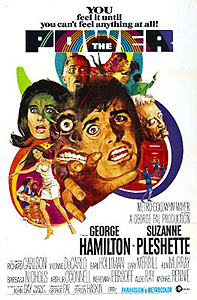

The Power (1968) ***

The Power (1968) ***

The Power is an unusually complex hybrid: part murder mystery, part conspiracy thriller, part sci-fi film. In many respects, this movie (which was brought to us by the same director-producer team responsible for War of the Worlds) plays like a big-budget, big-studio Scanners, but without all the exploding heads. And while it certainly lacks the impact of Cronenbergís later take on the same basic premise, itís more than good enough to make me wonder why nobody seems ever to have bothered to release it to home video.

Though it is unquestionably making great strides at the time, the US space program in the late 1960ís still has a number of important hurdles to overcome. Arguably the most challenging of these is the inherent limitations of the human bodyó simply put, we break pretty easily under the levels of stress to which transatmospheric liftoff or prolonged exposure to zero gravity or the extremes of temperature and radiation that one encounters outside of the Earthís atmosphere will subject us. And whatís more, most people can be expected to succumb to sheer pain even before the structural and mechanical tolerances of their bodies are reached. For this reason, NASA is spending quite a bit of money on a program of innovative pain research, in which student volunteers are paid handsomely to show up at the San Mineo laboratory of Professor Jim Tanner (George Hamilton, of The Dead Donít Die and Sextette) and his colleagues, where they are subjected to all manner of extreme physical discomfort. (I suppose pain research is the one field in which the rocket scientists cannot in good conscience rely on the foundations laid by their Nazi counterparts twenty-odd years before.) There is also a psychological component to Tannerís research, and it is here that things begin to get interesting. You see, one of Tannerís colleagues, anthropologist (nevermind that this is a job for a psychiatrist or a psychologist) Henry Hallson (Arthur OíConnell, from Fantastic Voyage and 7 Faces of Dr. Lao), had developed a questionnaire to be used in screening the student volunteers, which he had also given to his fellow scientists in order to give him a baseline by which to calibrate the answer key. As Hallson explains with almost unseemly eagerness when project director Dr. Van Zandt (Richard Carlson, of Riders to the Stars and It Came from Outer Space) introduces his team to Arthur Nordlund (Michael Rennie, from School Girl Killer and The Day the Earth Stood Still), the governmentís liaison to the lab, one of the scientists assigned to the project scored exceptionally high on this test. So high, in fact, that this personís mental capacity is literally tens of thousands of yearsí worth of evolution beyond what ought to be the upper limit of human potential. But because the tests were administered blind, Hallson has absolutely no idea which member of the team the aberrant scores belong to. Assuming it isnít Hallson himself, then it could be Tanner, Van Zandt, physicist Karl Melnicker (Nehemiah Persoff, from Psychic Killer and The Henderson Monster), biologist Talbot Scott (Forbidden Planetís Earl Holliman), or geneticist Margery Lansing (Suzanne Pleshette, whom we last saw in The Birds). To the immeasurable consternation of both Tanner and Van Zandt, Hallson essentially hijacks the meeting between Nordlund and his colleagues, turning it into something like a referendum on the results of his psychological questionnaire. When Hallson suggests the possibility that the person behind the odd scores might even exhibit powers of psychokinesis, Melnicker proposes a simple test: he shuts a pencil, point up, inside a heavy book, and impales a sheet of paper on itó surely a psychokinetic would be able to rotate so small a weight around the axis formed by the pencil? Hallson, however, rightly points out that if this superhuman personage should wish to remain unknown, then he or she would never go along with Melnickerís experiment. Hallson proposes that all six members of the team try to move the paper simultaneously; that way, he would be able to get confirmation of his hypothesis without exposing the mystery man or woman to specific scrutiny. Sure enough, the paper starts spinning.

It would seem, however, that secrecy is even more important to the possessor of this mysterious power than Hallson imagined, while that power itself is greater than even he dared to guess. That night, while Hallson is staying late at the lab to catch up on some work, the unknown psionic expresses his or her displeasure with the doctorís line of inquiry. When he tries to leave, he finds that the door leading out of his office seems to have disappeared! Whatís more, Hallson begins to feel a constricting sensation in his chest, and within moments, heís lying dead on the floor of a heart attack. Meanwhile, Tanner and Lansing are back at the formerís apartment, revealing themselves as the movieís primary love interest. No sooner have they turned out the lights, though, than they get a phone call from Hallsonís wife, Sally (Yvonne DeCarlo, of Satanís Cheerleaders and Blazing Stewardesses), asking if either of them has heard from her husband. Lansing convinces Tanner to drive out to the lab and see if everything is okay, and when they do, they find Hallsonís dead body being slowly mashed into putty in the centrifuge the scientists had been using to study the effects of g-forces on human physiology. The strange thing is that the centrifuge wonít respond to its control panel; Lansing has to cut the power to the machine in order to make it stop. Stranger still is the fact that this glitch mysteriously clears itself up by the time detective Mark Corlaine (Gary Merill, from Mysterious Island and Destination Inner Space) shows up with the police.

This is where the trouble for Tanner and his team really starts. It rapidly becomes obvious that whoever killed Hallson is trying to frame Tanner for the crime, and has figured out some ingenious ways to use his or her extraordinary mental powers to do it. First, Sally Hallson inexplicably forgets all about the call she made to Tanner which alerted him and Lansing to the dead manís disappearance. Then, when Corlaine runs a check on the personal records of each member of the laboratory staff, no one can find any trace of Tannerís credentials. Understandably assuming that this means Tanner had forged those credentials in the first place, Van Zandt fires him from the lab and Corlaine warns him not to leave town. The only clue Tanner has as to what in the hell is going on is a scrap of paper he found in Hallsonís office, on which the late scientist had written the name ďAdam Hart.Ē

It doesnít take Tanner long to find out that Hart had been an acquaintance of Hallsonís from his high school days, and it takes him scarcely any longer to decide to disobey Corlaineís orders and drive out to the run-down desert hamlet of Joshua Flats, Hallsonís home town, to see if any trace of Hart can still be found there. As is only to be expected from any halfway decent mystery, the pursuit of this first lead ends up raising more questions than it answers. Why, for example, does the floozy waitress at the gas station/cafe that Tanner stops at remember Hart as a tall, blue-eyed blonde, while Hallsonís parents remember him as a fellow Gypsy, dark-haired and dark-eyed? Is it true that Hartís family home burned to the ground just days before the man left town? Or is the place still standing, as the mechanic at the aforementioned service station implies when he offers to take Tanner to look at the place? And what is it about Hart that could command such loyalty that the mechanic would instead drive Tanner out into the salt flats around the nearby air force bombing range and dump him there to die, for no better reason than that Hart had told him ten years ago to kill any man who came to town asking about him? And why doesnít Sally Hallson have any memory of telling Tanner about Hartís connection to her husband once the weary and frustrated Tanner makes his way back to San Mineo?

All these questions take on a bit more urgency once more of Tannerís colleagues start dying. Tanner himself just barely survives a psychic assault similar to the one that killed Hallson, while Melnicker succumbs to an unexplained heart attack not 24 hours after he, Tanner, and Lansing go on the run together with the aim of ferreting out the killer. Nordlund, too, narrowly survives an attempt on his life, despite the fact that he isnít even really a member of Tannerís (now Van Zandtís) team. As for Van Zandt, he ends up meeting the strangest fate of all. When Tanner goes to his house to check up on him, he is told by Mrs. Van Zandt that the professor is not at home. But on the way back to his car, Tanner hears menís voices coming from a room on the other side of the house. Yepó itís Van Zandt alright, and heís got a veritable convention going on. Tanner can hear only a little bit through the thick glass of the windows, but Van Zandt is apparently a secondary player in Adam Hartís scheme to bring about some sort of totalitarian oligarchy of scientists; indeed, Hart should be stopping in for a visit any moment now. So itís a safe bet that the man in the 1968 Imperial Lebaron who tries to run Tanner over in the garden, who chases Tanner until he forces his car over the side of a drawbridge, and who finally doubles back and burns the Van Zandt mansion to the ground with all the assembled conspirators inside it is none other than Adam Hart. And can it be a coincidence that Nordlund drives a big-ass black Imperial, too? Or that Nordlund and Lansing both go missing right about the time that Corlaine and his cops fish Tanner out of the river? But if Nordlund and Hart are the same person, then hereís a real poser: Nordlund never took Hallsonís test. Who, in that case, could those superhuman scores have belonged to?

I only wish The Power did as good a job solving the mystery that serves as its driving force as it does setting it up. This movie is absolutely gripping when itís stringing the audience along, keeping us nearly as confused as Jim Tanner, but when the time comes to tie up all the loose ends, it somehow seems like director Byron Haskins and screenwriter John Gay donít really have their hearts in it. Itís a pitfall Iíve seen a lot of mysteries fall into, failing to come up with an answer that is as satisfying as the question. Furthermore, the final confrontation between Tanner and Hart is handled in an awkward manner that suggests that Haskins was trying just a little too hard to come up with a strong visual presentation of an event that does not obviously lend itself to being presented visually. The rest of the movie is so good, though, that Iím willing to put up with the wobbly ending, and besides, itís kind of cool to see so many familiar faces from the early to mid-50ís showing up here in the waning days of their careers.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact