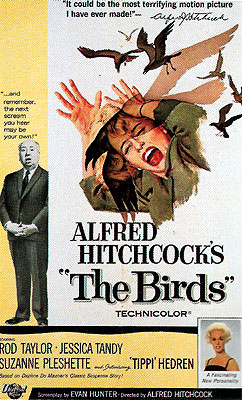

The Birds (1963) ***

The Birds (1963) ***

Call me a philistine if you want, but I think Alfred Hitchcock is overrated. Yes, his films are always very pretty to look at, he generally got good performances out of his actors, and most importantly, he was not afraid to take chances. All of these things are certainly commendable, all the more so because of their inexplicable rarity, but I tell you there is more to making great movies than that. It may simply be that I’m too much a product of my times, but Hitchcock has always seemed to me less the Master of Suspense than the Master of Impatience-- I find myself spending an inordinately large proportion of his movies’ running times thinking, “look, damn it, it’s quite obvious what you’re trying to get at here, so will you please stop dicking around, and just fucking get at it already?!” The Birds is a perfect example. There are more beautiful, artfully composed shots and sneaky camera tricks in this movie than you could count if you did nothing else all day, but at least half of them are completely unnecessary to what ought to be the main point of the movie-- telling the goddamned story-- and a few of these directorial flourishes actively get in the way. Essentially, what Hitchcock has done here is find a way to use his undeniable command of visual composition to disguise the fact that he’s really just padding the film.

It’s a shame, too, because with a little restraint in this department, The Birds could have been one of the best monster movies of the 1960’s. In case you’ve somehow missed hearing about it, this movie (which was based on a short story by, of all people, Daphne DuMaurier) concerns an inexplicable outbreak of lethal aggressiveness against humans on the part of the birds of Bodega Bay in northern California. You could think of it as a precursor to all those “Mother Nature’s revenge” flicks of the 70’s, with the very important distinction that it has no apparent social or ecological axe to grind, and it had the potential right from the beginning to be vastly better than such witless entries in the genre as Frogs or Terror Out of the Skies for that very reason. These birds don’t turn hostile because of toxic waste or nuclear fallout, or because of some dimly-conceived, hippyish notion of nature’s vengeance; they just start killing one day, and nobody has any idea why.

But before we get to that, we must first wade through a full hour of heavily padded character development. On the day that ornithological craziness first begins to surface in Bodega Bay, a young woman named Melanie Daniels (Tippi Hedren, in her first film role) has a chance meeting in a San Francisco pet shop with a lawyer by the name of Mitchell Brenner (Rod Taylor, from World Without End and The Time Machine). Both have come looking for birds (Melanie for a myna, Mitchell for a pair of love birds for his eleven-year-old sister), but that is not what brings them together. You see, this isn’t exactly the first time the two have crossed paths; Mitchell says he saw Melanie in court-- something about a practical joke that resulted in the destruction of somebody’s plate-glass window. In this early phase, their relationship will largely be advanced by a prank of byzantine complexity, which begins with Mitchell pretending to try to buy his birds from Melanie (who he knows does not work at the pet shop), and the girl (apparently a compulsive liar as well as a prankster) impishly playing out her appointed role in this case of “mistaken identity”. Eventually, for reasons that don’t make a hell of a lot of sense, Melanie ends up sneaking into Mitchell’s family home in Bodega Bay with a pair of the very birds which he had pretended to try to buy from her. Naturally, we’re being set up here for a romance between the two, the development of which will be complicated by the influence of three people: Mitchell’s jealous mother (played by Jessica Tandy, who was at this point merely old, rather than unfathomably ancient), his little sister Cathy (Veronica Cartwright, who as an adult, would earn distinction as a monster hors d’oeuvre in Alien), and his ex-girlfriend Annie (The Power's Suzanne Pleshette).

The whole business seems like an awfully large investment of time and energy on Hitchcock’s part for something that is of essentially secondary importance, but I guess the idea was that the more time we spent with these people, the more we would care about them when the shit hit the fan. Unfortunately, the effort was wasted (on me, anyway) because Annie and Cathy are absolutely the only characters in this movie for whom I did not feel an intense, instinctive dislike from the moment they first opened their mouths. It’s the same thing that stops me from liking anything written by Brett Easton Ellis or F. Scott Fitzgerald, two authors whose works I would certainly appreciate more if they ended with the entire dramatis personae being pecked to death by homicidal seagulls. I’m sure this is the exact opposite of the reaction Hitchcock was shooting for, but when the three major characters are a compulsive liar, a self-righteous jerk, and a control freak for whom no one is ever good enough, I can’t really imagine any other.

Anyway, the swooping and pecking finally begin in earnest (there were a couple of ostensibly tension-building isolated incidents early on) at Cathy’s birthday party, which is broken up by a flock of bloodthirsty gulls. None of the children are killed in the attack (this is 1963, you realize), but there are a few minor injuries, and everyone involved is quite shaken up. That night, the Brenners’ living room is invaded by hundreds of enraged sparrows, which spew forth from the chimney like water from a burst main, and the next day, the local vendor of farming supplies is found dead in his bedroom amid a scene of unbelievable chaos and destruction. His eyes have been pecked out, and there are several dead birds in his room. The situation reaches critical mass with another attack on a group of children, this one occurring at the local elementary school (where Annie is a teacher). In what is easily the best scene of the movie, a horde of huge crows congregates on the playground, lying in ambush for the defenseless humans they seem to know will soon emerge from the school. Finally, the birds stage a full-scale assault on the town, which leads, via a series of accidents, to a fire and an explosion at a gas station. Rather than dispersing after this attack, as they have after each one up to this point, the birds remain in the area like an occupying army, trapping the people of Bodega Bay in their houses or forcing them to flee for safety in the outlying regions.

At last, in a scene that surprisingly prefigures Night of the Living Dead, Melanie and the Brenners must fend off a renewed siege on the family house, which they have fortified as best they can. It is here that the movie’s most famous scene occurs, in which Melanie finds herself trapped alone in the bird-infested attic. And like Night of the Living Dead, The Birds comes to no decisive ending as far as the larger situation is concerned. When the surviving characters leave Bodega Bay, it remains in the hands of its avian conquerors.

The Birds illustrates the problem with taking chances-- by definition, to take a risk is to accept the possibility of failure. Trying to make a highbrow monster movie is always a risky endeavor, and while I would certainly not call this film a failure (indeed, it really is quite good, despite my complaints with it), I will say that in the hands of anyone without Alfred Hitchcock’s technical skill, it would have been. The inherent strength of the movie’s premise, combined with Hitchcock’s remarkable visual flair and solid performances all around from the cast, are enough to keep the film on its feet, but the movie is saddled with far too many sequences that seem to exist for no reason other than to dazzle us with Hitchcock’s compositional virtuosity. There is only so much self-consciously clever directorial tomfoolery that any movie can support, and The Birds comes perilously close to that limit.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact