The Golem/The Golem: How He Came into the World/Der Golem: Wie Er in die Welt Kam (1920/1921) ***

The Golem/The Golem: How He Came into the World/Der Golem: Wie Er in die Welt Kam (1920/1921) ***

For people who are as seriously into movies as I am, there are few things more annoying than the phenomenon of the lost film. I realize, of course, that I’m never going to see the great majority of the movies yet made that I might potentially enjoy— there are just too many of the damn things floating around, thousands of them have never been released to home video, and thousands more have simply never been made available in the English-speaking world. But as unlikely as it is that I’ll ever get to see most of the works of Jean Rollin, Jesus Franco, or Jose Mojica Marins, we’re still just dealing with unlikelihood. Fascination and The Perverse Countess and When the Gods Fall Asleep are out there. If I didn’t mind spending some extra money on the tapes or discs themselves; if I wanted to invest the time that would be necessary to track them down; if I felt like going through the expense and hassle of procuring a PAL-compatible home video rig; if I had the gumption to brush up on my Spanish and learn Portuguese and French— doing any or all of those things would bring many of those unlikely movies within my reach, and all I’d have to worry about then would be finding the time to watch them. It’s a different matter with lost films, though. With something like London After Midnight or The Janus Head, the issue is that they’re just gone. I’m not going to see them because they’re no longer out there to be seen. Back in the teens and early twenties, few people had yet considered the possibility that anybody might want to see a movie after its initial release, and most films were simply thrown away after their screening engagements elapsed. And of those that were saved, multitudes more have been lost because the naturally occurring acids in their old-fashioned nitrocellulose film stock have literally eaten them away to nothing over the years. Get to the point, you say? Okay, fine— hardly anybody realizes this, but The Golem/The Golem: How He Came into the World/Der Golem: Wie Er in die Welt Kam is actually part three of a series, the first two installments of which have been lost.

The first movie in the series was called Der Golem. It was released in Germany in 1914, and made its way Stateside a year later, when it played under the title Monster of Fate. In it, the golem was discovered in a subterranean vault by a work crew digging a well on the outskirts of modern-day Prague. The inanimate creature was bought by a Jewish antique dealer, who learned how to activate and control it from a book he acquired from an impoverished scholar. The shopkeeper used the clay giant initially as a sort of superhuman handyman, then as a chaperone for his daughter after he learned that she was having an affair with a gentile count. The latter plan backfired when the golem fell in love with the girl, and she used its affections to create an opportunity for escape. The living statue then tracked her to the costume ball where she and the count were to rendezvous, and went berserk in one of the earliest cinematic monster rampages on record. Monster of Fate was followed two years later by what some film historians consider to be the first horror movie sequel in history, The Golem and the Chorus Girl/Der Golem und die Tanzerin. In a move that startlingly prefigures the creation of Bride of Frankenstein nearly twenty years later, The Golem and the Chorus Girl repositioned the series as a comedy; apparently the story concerned a man who had played the golem in a movie pretending to be the real monster as part of a practical joke— I’m not entirely sure just where the titular chorus girl enters into it. Then in 1920, after The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari had ushered in the age of German Expressionism, Paul Wegener, the writer/producer/star of the two golem films, got to work on this movie, which went back to explain the origin of the monster that was unearthed by Monster of Fate’s well-diggers.

Theoretically, our setting is Prague in the year 1580. Really, what we’ve got here is a spectacular German Expressionist stage set so surreal as to make you wonder if the Kaiser’s scientists discovered LSD during World War I and just didn’t tell anyone about it. Rabbi Loew (Albert Steinruck) is up in the observatory tower that tops the roof of his house in the city’s Jewish ghetto, peering at the night sky with his telescope. Astrology is just one of Loew’s many talents, and it is his considered opinion that “the stars predict disaster” for his people on this particular night. Going downstairs, he orders his son— or maybe his son-in-law— Famulus (Ernst Deutsch, who later migrated to America, where he made movies like Isle of the Dead under the name Ernest Dorian) to take him to see another rabbi named Jehuda (Hans Stürm, of Warning Shadows). Presumably, the idea here is to compare notes and begin planning how to deal with whatever disaster it is that the stars portend.

As it happens, the foretold disaster takes the form of an imperial decree. The Emperor Ludwig (Otto Gebühr) has gotten it into his head that the Jews of Prague are all in league somehow or other with the devil, and he wants the ghetto evacuated within 30 days. Ludwig sends a knight named Sir Florian (Lothar Müthel, from the 1926 version of Faust) to the Jewish quarter with a copy of his proclamation of expulsion, and the gatekeeper of the ghetto tells the imperial emissary that Rabbi Loew is the man he needs to see. The next scene is important for two reasons. First, it gives Loew some idea of what sort of catastrophe he’s about to face. Second, it brings Sir Florian into contact with Loew’s hypothetically beautiful daughter, Miriam (Lyda Salmonova, who had already appeared alongside Wegener in The Student of Prague and both previous golem films). “Hypothetically beautiful?” you ask? Well let’s just say that I don’t know enough about cultural standards for feminine beauty in 1920’s Germany to call it one way or the other, but in a modern American context, Lyda Salmonova would be no great shakes even if her acting in all of her many love scenes didn’t make her look like she was doped to the gills on ecstasy. But since I don’t buy the mincing Sir Florian as a raging inferno of sexual enticement, either, I’m probably just looking through anachronistic eyes. In any event, the two young people fall instantly in love, while Loew asks Florian to request an audience with the emperor on his behalf, reminding the envoy that Loew had served His Majesty well in the past as a doctor and an astrologer.

With the knight gone back to the castle, Loew gets together with Jehuda and starts scheming. Down in his basement, Loew has a secret stash of grimoires, one of which contains an instruction manual for how to make and animate a golem. A golem, for those of you who are not up on these things, is a full-sized clay statue of a man, which is brought to life by means of a magical formula written somewhere on its person; removing or erasing this formula turns the magical creature off again. In some variations on the story, the incantation is carved directly into the statue’s forehead; in others, it is written on a slip of parchment which is then placed in the golem’s mouth. In this case, the inscribed parchment is concealed within a pentagram-shaped amulet affixed to the creature’s chest. The only snag here is that Rabbi Loew doesn’t know the magic words that will impart life to the golem. His books tell him that he will have to summon up the demon Astaroth in order to gain the knowledge he seeks.

This brings us to a very interesting scene, which is of great historical importance in the world of fantasy and horror cinema. The scene in The Golem in which Loew does his business with Astaroth marks the first time a Satanic personage was portrayed onscreen entirely by means of special effects. Previous cinematic devils— and there were an enormous number of them, at least over in Europe— had always been played by a regular human actor. When Loew calls up Astaroth, the demon appears as an immense, glowing puppet head with horns and long, pointed ears, belching smoke from its mouth with every word it speaks. And in an especially cool touch, the life-bestowing incantation appears written on the empty air when Astaroth utters it. Now that Loew possesses all the necessary information, he sets to work making his golem (Paul Wegener himself, as in both of the preceding movies).

Now it might seem a bit odd that Loew is making a golem in response to an imperial expulsion decree, but the old rabbi has his reasons. A few days later, Sir Florian returns with a letter from Ludwig, granting Loew his audience before the imperial court. When Loew sets off for the palace, he brings the golem with him— and believe you me, it causes quite a stir at the palace. But oddly enough, Rabbi Loew does not jump right into pleading his people’s case to Ludwig and his ministers, but instead begins entertaining the court with a magic show. Warning his audience of grave consequences if they laugh or heckle the display, the rabbi opens up a window in time, so that Ludwig and his courtiers may eavesdrop on the earliest history of the Jewish people. But when a dour-looking Moses enters the frame, Ludwig’s jester begins cracking wise. Incredibly, the old patriarch hears the giggling of Ludwig’s guests across the ages, and sends a curse forward in time to smite them. The time window closes, and the ceiling of Ludwig’s castle begins slowly sinking, threatening to crush everyone beneath it. The emperor begs Loew to save him, promising to rescind his expulsion decree in exchange, and the wily rabbi calls forth his golem. The great clay hulk raises its arms above its head, and stops the descending ceiling in its tracks, giving everyone in the palace ample time to escape. Having accomplished his mission at the palace, Rabbi Loew and his golem return home.

But something is going on back at the Loew place that will have grave consequences in the immediate future. While her father was away, Miriam contrived to sneak Sir Florian up to her bedroom for some discreet, off-camera fun. The knight is still in the house when Loew returns, and there is no way to sneak him back out again as long as dad is around. And Loew doesn’t plan on going anywhere any time soon, because further research has convinced him that the golem must be destroyed immediately now that its purpose has been served— the planets are on their way to a configuration in the sky that will allow Astaroth to take control of Loew’s creation, in which case it will go berserk and begin destroying everything around it. But the rabbi is interrupted before he can make any real headway on this project, because the Jews of Prague have organized a celebration of thanks for his rescue mission, and it is religiously necessary that he be present during it. That means the golem will be intact and unattended when Famulus catches his wife/sister/whatever she is to him consorting with a gentile, offering itself as an open invitation to exact hellfire-fueled revenge. Famulus reactivates the golem, but when he does so, he finds that it isn’t just Sir Florian the monster wants to destroy. Famulus, Miriam, and indeed the entire city of Prague will also do nicely.

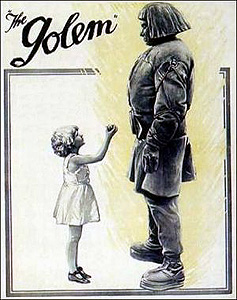

The Golem is often cited as an influence on James Whale’s 1931 Frankenstein, and indeed, there are a number of remarkable parallels. Not only do both movies involve the creation of superhumanly powerful artificial men, Wegener’s performance as the golem itself has much in common with Boris Karloff’s later portrayal of the Frankenstein monster. Both creatures are mute, lumbering, slow-moving brutes with stiff gaits and an utter failure to understand their own immense strength. There are also any number of smaller suggestive similarities scattered throughout the two films. Famulus, who fears and hates the golem even as he assists in its creation, bears a marked resemblance to the lab assistant, Fritz, in Frankenstein, a resemblance which extends even so far as the central role that both characters play in setting off the monsters’ eventual rampages. Both movies’ monsters encounter little blonde girls near the end of the story, and attempt to play with them with unexpected results. (Well, unexpected by the monsters, anyway...) Both films feature unsuccessful attempts by the monster-maker to destroy his creation before it can get loose and harm the innocent, both involve fire in the climactic scene, and both— of perhaps the greatest importance— feature men who create nearly unstoppable menaces for basically noble and commendable reasons. Furthermore, it’s difficult to imagine that the production design for Frankenstein was arrived at in isolation from The Golem. The sets occultist architect Hans Poelzig designed for The Golem are distinguishable from those used in the later Universal horror films only as a matter of degree. The Golem’s sets are more stylized and more avowedly nightmarish than those in the subsequent American horror flicks, but the underlying design esthetic is the same. And it is scarcely surprising that it should be thus— Ernst Deutsch wasn’t the only member of the cast and crew of The Golem who would make their way across the Atlantic over the next two decades. Cinematographer Karl Freund would go on to be a big name at Universal during the 30’s and 40’s, while Edgar G. Ulmer, who directed Universal’s The Black Cat, was part of the crew that built Poelzig’s amazing sets for this movie. And considering how many of Universal’s high-ranking producers— Carl Laemmle foremost among them— were German immigrants, it would have been more of a shock had the first generation of Hollywood horror films not taken so many of their cues from their German ancestors.

Home Alphabetical Index Chronological Index Contact